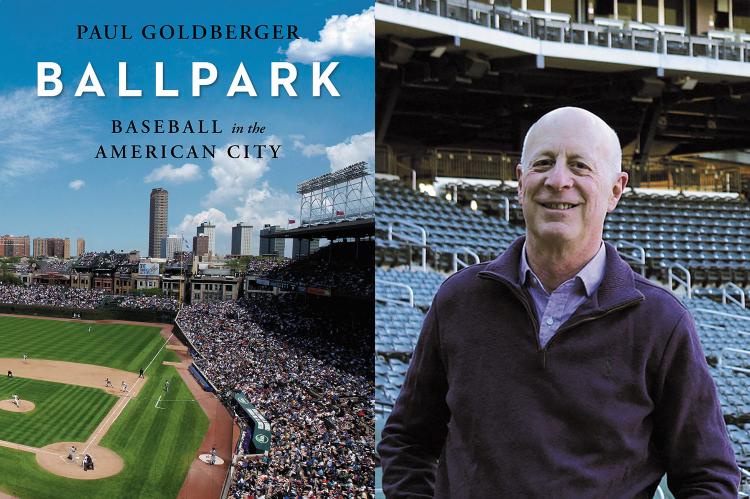

“Ballpark”

Paul Goldberger

Knopf, $35

Fenway is on my bucket list. A lifelong Yankees fan, I hanker for a glimpse of the enemy’s home base, older even than the original Yankee Stadium. And my desire to see the Green Monster in person has only been heightened by Paul Goldberger’s highly informed and interesting “Ballpark: Baseball in the American City.”

But Mr. Goldberger’s tastes in playing fields are based not on his allegiances or prejudices toward certain clubs; indeed, it’s not clear how much he likes or how closely he follows baseball. He’s more interested in the architecture of stadiums, as one would expect of one of America’s foremost architectural critics.

His criteria have to do primarily with siting and design — the ideal being a baseball park that is part of the urban setting, embedded in the life and movement of its city, offering views over the outfield stands of Pittsburgh or San Francisco or Detroit; a park that is comfortable and cozy, open to the sky and the elements, devoid of carnivalesque attractions and other distractions. The field of dreams itself, the greensward that defines the perimeters of play, is indeed a kind of park, an oasis of “nature” (if grass can be considered natural) setting off and enriching its urban context.

Accordingly, he despises what he calls “concrete doughnuts” — featureless stadiums in the suburbs, surrounded by parking spaces, some of them enclosed or with retractable roofs that cut the spectators off from their surroundings, making them inhabitants of a bubble rather than citizens of a community with its own particular sense of style and place.

The book is a history with knowledgeable commentary; it takes us from the crude wooden grandstands of the 19th century through what the author sees as the dynamic arc of ballpark construction: first, the grand old places like Ebbets Field, Fenway Park, Shibe Park, and Wrigley Field, nestled (not always comfortably) into pre-existing neighborhoods; second, the era of larger, more self-contained venues shaped by the flight to the suburbs and the increased reliance of fans on the automobiles after World War II, typified by Metropolitan Stadium located not in Minneapolis or St. Paul, but in Bloomington (which later became the home of, fittingly, the Mall of America), and Dodger Stadium, “an island in the midst of a sea of parking” that expressed the sensibility that created Disneyland; followed by the time of the concrete doughnuts (many of them designed for football as well as baseball, a terrible marriage), like R.F.K. Stadium in Washington, Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh, Bush Memorial in St. Louis, and Shea Stadium, the first home of the Mets, squatting in a bleak and unlovely part of Queens and ignoring Manhattan only 10 miles away.

As baseball spread from the Northeast to the north, south, and west (which would have been impossible without transcontinental air travel), owners and builders got farther and farther from urban life and public transportation, insulating baseball from weather with domed stadiums (the Astrodome was the first) and arenas with retractable roofs and, because grass won’t grow indoors, artificial playing surfaces like Toronto’s.

But then came a retro period, a return to the idiosyncratic charm and city roots of the old places, embodied in Mr. Goldberger’s favorite stadium of all: Camden Yards in Baltimore — small, inviting, citified, comfortable, and aesthetically pleasing, integrated into the city itself in a manner of which Jane Jacobs (one of Mr. Goldberger’s heroes) would have approved.

Whether or not it’s a great asset to the Orioles isn’t discussed. Its Lilliputian dimensions make it a favorite of other teams’ sluggers; I remember one of Don Mattingly’s Yankee teammates quoting him, when he first saw those right-field stands only 318 feet from home plate, muttering, half-aloud, “Oh, yeah!” And indeed, the Yankees have feasted there for decades, sending home runs over the fence and onto Eutaw Street with astonishing regularity.

Mr. Goldberger pays attention to the dimensions of all these playing fields, partly in service to his notion that while a baseball infield is a strictly limited and precisely defined space, outfields are, in theory, infinite, extending past the confines of the stadium forever. And often, they were almost that; the history of ballpark modification is that of bringing the fences in as fans demonstrated their preference for home runs over pastoral meditation, the most dramatic example being the short porch in Yankee Stadium’s right field, which is what makes that place truly “the house that Ruth built.” Ruth himself complained about Cleveland Municipal, “A guy ought to have a horse to play the outfield here.”

I don’t think outfields are in any sense infinite; they are the most important boundaries on the field, along with the foul lines. The locations of the fences can determine whether a ball will be caught harmlessly on the warning track or change the outcome of the game by driving in as many as four runs. They also provide outfielders with the challenge of fielding line drives that find the gap and bounce around the nooks and crannies at the base of the wall (or, in the case of Wrigley, losing themselves in the ivy that covers the outfield perimeters).

The shape of the available site determined, in many cases, the dimensions of the field, which tended therefore toward asymmetry, and a majority of parks, it seems, were built shorter in right field — perhaps because in the game’s early days, most batters were right-handed, which meant their power stroke was to left field.

Mr. Goldberger fails to mention that when lefty Ted Williams and righty Joe DiMaggio were playing, there was talk of trading them because each would have found the other’s home park more conducive to their sweet strokes. The idiosyncratic nature of ballparks is part of their charm and part of the game itself; Mr. Goldberger approvingly quotes Philip Lowry’s comment that “Ballparks with no idiosyncrasies are poor ballparks.”

Commercial interests, which of course always played a large part in the building of baseball fields, began to predominate as the stakes got higher. Owners discovered that they could make huge profits from ancillary features like outdoor food courts, carnival rides, and shops. Mr. Goldberger mentions that one team owner was worth $3.4 billion, which ranked him only fourth in the wealth of his peer group. (I’ll bet George Steinbrenner was on that list.)

Stadiums began to feature luxury boxes and suites, which often interfered with the other fans’ views and further separated the experience from the city, if indeed there was one, threatening to turn the whole place into “an upscale bubble.” The final phase of ballpark construction was typified by The Ballpark in Arlington, located halfway between Dallas and Fort Worth, “an urban palazzo in search of an urban setting.”

And these parks tended to be enormous. Mr. Goldberger’s dictum is that any arena with a seating capacity over 50,000 is too big, moving the game too far away from its spectators.

But more recently, he believes, ballpark design has taken a turn for the better. He likes Safeco Field in Seattle, forgiving its half-dome, which he calls more an umbrella than a roof. And he applauds AT&T Park, San Francisco’s brilliant replacement for Candlestick Park (which was hated by fans and players alike), sited right on the iconic bay, which is visible from almost every seat, in which kayaks weave back and forth, hoping for a ball to be hit out of the park and into what is known as McCovey Cove, a feat regularly accomplished by Barry Bonds when he was a member of the Giants.

Citi Field, in Mr. Goldberger’s eyes, is a huge improvement over Shea Stadium, and the new Yankee Stadium (its third iteration) restores much of the luster that was lost when the original was renovated in the 1970s.

Mr. Goldberger records — perhaps in more detail than necessary — the Byzantine complexity of the political and economic machinations that went into the conception, planning, design, funding, and construction of dozens of baseball stadiums. I couldn’t tell the players even with the scorecard he provides, and didn’t care all that much which nabob or mayor or alderman got what zoning variance passed to make it all possible.

But that is a small matter. This is an invaluable book, with delicious stories and insights into both baseball and urban studies.

Richard Horwich taught literature at Brooklyn College and New York University. He lives in East Hampton.

Paul Goldberger, who lives in New York and Amagansett, is a contributing editor for Vanity Fair. He was the architecture critic for The New Yorker from 1997 to 2011.