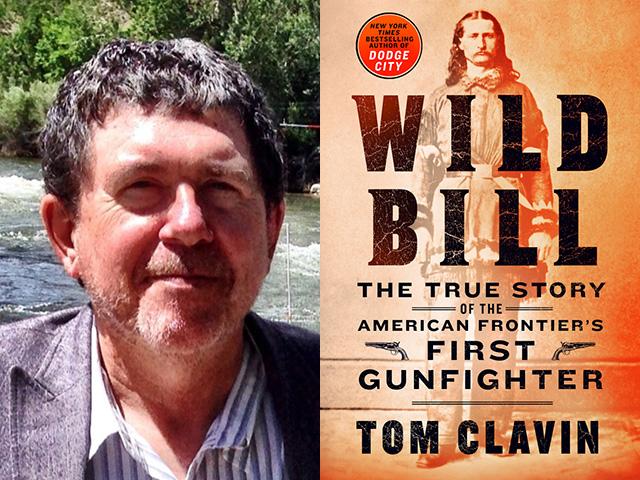

“Wild Bill”

Tom Clavin

St. Martin’s, $29.99

The story of Wild Bill Hickok’s life is so full of legend and myth that it would be difficult for anyone to sift through it all to reveal the absolute truth, yet that is what Tom Clavin claims to do in his new work, “Wild Bill: The True Story of the American Frontier’s First Gunfighter.”

Was Hickok, who the author posits is “one of the most intriguing figures in American history,” a ruthless killer whose sleep was undisturbed by murdering men in cold blood, or a sympathetic figure who “only killed those who needed to be killed”? Mr. Clavin’s fast-paced biography does a good job of laying out the facts, but ultimately lets the reader decide.

James Butler Hickok was born in Homer, Ill., on May 27, 1837, to William Hickok and Pamela (Polly) Butler. William was a farmer, a businessman, and an abolitionist. The family’s home was a stop on the Underground Railroad, and his sons were often pressed into service to smuggle wagonloads of escaped slaves to safety, possibly whetting young James’s appetite for daring adventure. In 1852 William Hickok died, and the family moved from a farm to Homer proper.

As a child James enjoyed reading exciting tales about Daniel Boone and Kit Carson. Charged with securing game for the family table, he used those hunting forays to hone his shooting skills. But life in town made him restless, and when he was 19 he and his brother Lorenzo set off to find their fortune in the West, landing in the middle of the battle that would be known as Bleeding Kansas.

It was not a good time for new settlers in Kansas in 1856 — the battle between pro-slavery and antislavery forces created a toxic environment of war and violence. Hickok tried to stay above it, taking what work he could find, making some friends, courting a few women, and writing home to his mother. He also changed his name; friends started calling him Bill — the “Wild” title came a bit later, probably conferred on him after he sorted out a bar fight in Independence, Mo.

In 1861, in a fight at the depot of the Overland Stage Company, he killed for the first time — a man named David McCanles. When a jury acquitted Hickok on the basis of self-defense, he wisely enlisted in the Union Army and got out of town. His years in the Army as a scout and guide (and possible spy) improved his shooting skills and taught him to think quickly on his feet. A high noon-type shootout with Davis Tutt in Springfield, Mo., in 1865 called upon these skills and earned him a reputation as the fastest gunslinger on the American frontier.

From there the legend grew. Newspaper reporters, writing for thrill-starved readers, told of an exotic young frontiersman who was the fastest, most accurate “shootist” the West had ever seen. Hickok’s elegant personal appearance only added to the allure. In a time of tobacco-stained, filth-encrusted cowboys, he presented a kind of Western elegance, and insisted on bathing every day, even if it was in a creek.

A reporter for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, George Ward Nichols, described him: “He was over six feet tall and wore yellow moccasins,” Mr. Clavin paraphrases. “A deer-skin shirt hung jauntily over his shoulders,” revealing, in Nichols’s words, “a chest whose breadth and depth were remarkable. . . . There was a singular grace and dignity of carriage. . . . A mass of fine brown hair falls below the neck to the shoulders.”

His life’s motto was “Be the toughest and the quickest, and kill those who need killing.” To that end he was always well armed, his weapons of choice usually being a double-action Colt .44, a .41-caliber derringer, and a bowie knife tucked into his belt. He sometimes carried a shotgun, and reveled in shooting exhibitions that demonstrated his skills.

His reputation as a feared gunslinger grew, yet he was also known to be friendly to children and chivalrous to the persecuted. He sometimes came out with guns blazing, while other times he used charm to diffuse a situation and convince opponents to back off and live another day.

Mr. Clavin doesn’t tally an exact body count, but as the number of dead men increased, Hickok came to the uncomfortable realization that his notoriety also made him a marked man. And the West was changing; cities were trying to attract families and were no longer as welcoming to violent gunslingers with a penchant for booze, gambling, and gunfights.

As robustly as he recounts the beginning, Mr. Clavin leads us almost reverentially to the end that we know has to come. Hickok’s “nerves of steel” began to weaken. He had trouble with his eyesight; he was mired in melancholy that a brief but happy marriage could not assuage. He dropped his guard, and in an instant it was over. He was 39 years old.

The author delves into the lives of other gunslingers and friends such as Buffalo Bill Cody, Kit Carson (his childhood hero), and Calamity Jane. I began to wonder about the relevance of these side stories and became impatient for a return to the life of the main character. But all roads eventually converge, Mr. Clavin weaves in all the loose ends, and we are left with a sorrowful but deeper understanding of a complex character.

We shouldn’t like him, much less respect him, but somehow, despite it all, in some deep part of us we do.

Antonia Petrash is the author of “Long Island and the Woman Suffrage Movement.”

Tom Clavin’s previous book about the American West was “Dodge City.” He lives in Sag Harbor.