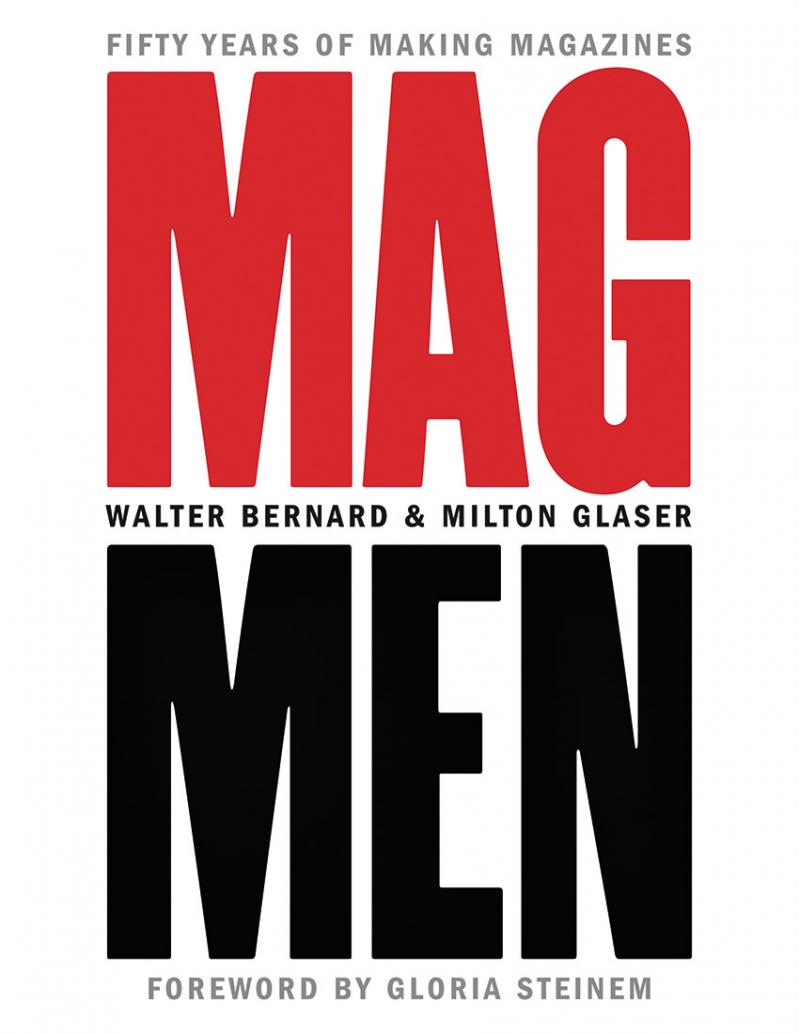

“Mag Men”

Walter Bernard and Milton Glaser

Columbia University Press, $34.95

In her foreword to “Mag Men,” Gloria Steinem writes that if she had to choose just one medium it would be magazines. As for her reasons — “more depth and visual pleasure than newspapers, more availability on the street than books, and less expense and more fact-checking than the internet” — who can disagree?

Perhaps only those young enough to have digital as their first media language. The rest of us, however, discovered that good magazine reporting had the power to put the reader inside the skin, inside the head, even behind the eyes of characters in a story.

Still, few of us buy stacks of magazines today the way we used to. We probably couldn’t even if we tried because the graveyard of print journalism is littered with skeletons of dead glossies, with more titles seemingly heading that way or, if they’re lucky, onward to a digital afterlife.

So, “Mag Men” by Walter Bernard and Milton Glaser, the formidable graphic designers whose work with New York magazine left a huge imprint on American journalism, only adds to this bleak realization that an era has ended. That the golden period of magazines, the heyday of modern literary journalism, is now officially over.

More optimistically, the book is a wonderful retrospective of a 50-year legacy of editorial work in a creative profession once known as magazine art direction. When art, culture, storytelling, photography, design, and inventive typography tailored to each article were sandwiched so alluringly between front and back covers that it captured the attention of ordinary people and influenced editors and designers for years to come.

And no one gained more national, even global, prominence as magazine (and newspaper) art directors as Mr. Bernard and Mr. Glaser. (Their design fame reached far beyond print journalism — Mr. Glaser is responsible for the now-ubiquitous “I Love New York” logo and Brooklyn Brewery’s, while together they designed the title sequences for the movies “Sleepless in Seattle” and “You’ve Got Mail.”) But this book centers on their extraordinary half-century of print work, during which they revolutionized the look of magazines.

In addition to short essays and anecdotes about the industry, famed contributors, and principals in the publishing world, the book is filled with fabulous firsthand accounts of the process, told by the duo as well as other designers, photographers, illustrators, writers, and editors.

Three chronological, image-laden chapters chart their legacy: 1968 to 1977, when New York magazine was born; going their separate ways after Rupert Murdoch’s hostile takeover of the magazine in 1977; 1982 to the present day, when the designers formed WBMG, an editorial and design and development company in Manhattan.

The most interesting of the chapters is, naturally, the first, titled “Shall We Start a New Magazine?” A brief introduction explains the conception of a magazine that would become the prototype of a city weekly.

“We began working together on July 1, 1968. The pace was hectic from the start, but we quickly found our stride as art director and design director. With lean budgets and a brilliant staff, we managed to produce a weekly magazine that, if far from perfect, had a real impact on the city and beyond. What follows is a close look into the inner workings at New York: the thinking behind most graphic decisions, including some clever ideas and some stupid mistakes.”

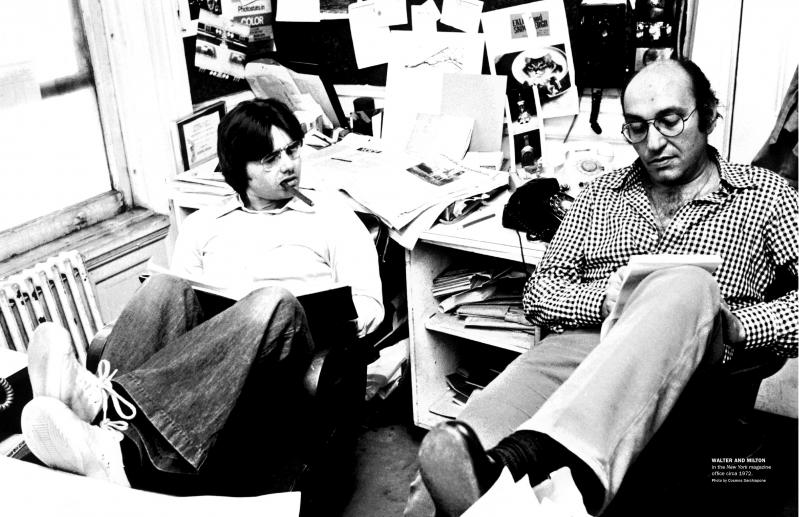

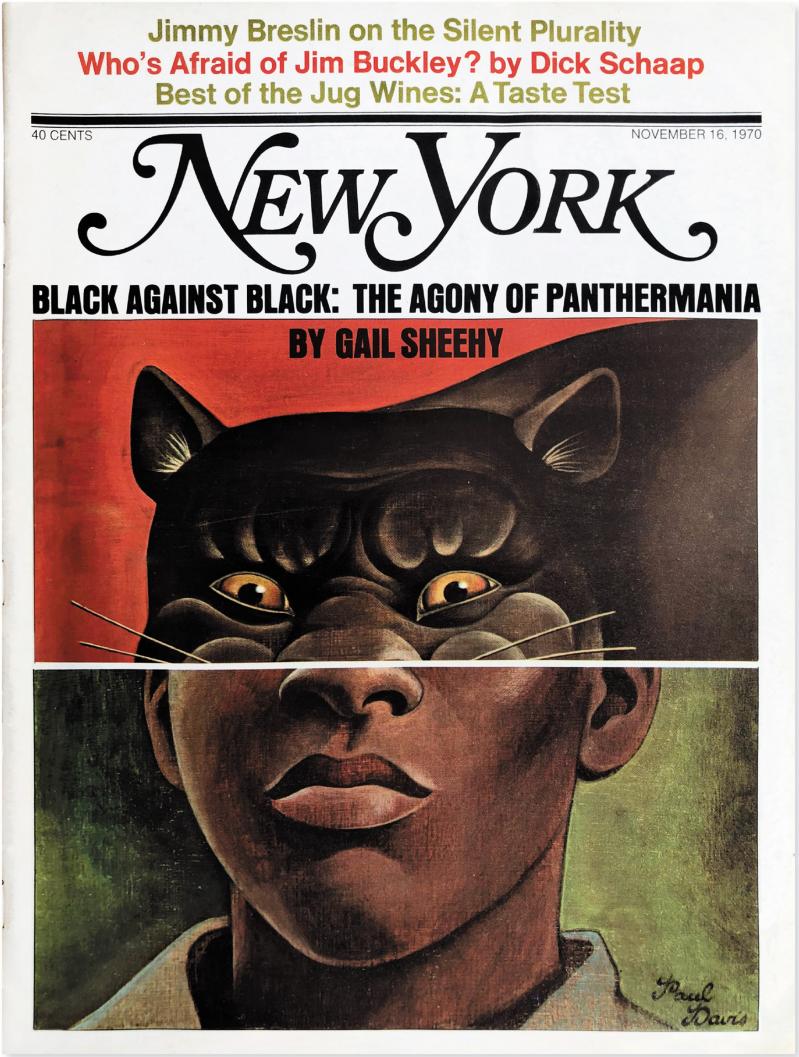

And what glorious pages follow: Lovely black-and-white photographs of editorial meetings, some of their most iconic New York magazine covers, and revolutionary spreads that delighted readers, shocked others, and often rattled nervous advertisers. A few hilarious anecdotes are included, such as when Mr. Glaser and Clay Felker, the legendary editor who helmed New York magazine, consulted the I Ching, the Chinese book of changes, for guidance on whether they should start a new magazine after New York, the Sunday supplement magazine of The New York Herald Tribune, had folded. It’s a real ’60s moment.

The book is as much a tribute to Felker’s visionary editorship as it is to the magazine’s graphic personality; it was the collaboration that helped make the New York weekly one of the city’s cultural behemoths. Felker, who died in 2008, hired Tom Wolfe to write for the magazine, while cultivating the likes of Jimmy Breslin, Nora Ephron, Anna Wintour, Ken Auletta, Gloria Steinem, Pete Hamill, and Gail Sheehy (who became Felker’s third wife).

The 13 years he ran New York magazine are illustrated in the articles and cover stories that served as sociological studies of urban life: the culture of Wall Street, the culture of shady city politics, cop culture, Mob culture, drug culture, youth culture, immigrant culture, prostitution rackets, New York’s dysfunctional, power-hungry culture, and the city’s unapologetic elitism. Felker also introduced what he called the magazine’s “secret weapon,” its service coverage: where to eat, shop, drink, and live.

But it was the depth of reporting that he demanded — almost an entire issue in 1970 was devoted to Wolfe’s account of a Black Panthers’ fund-raiser held at Leonard Bernstein’s apartment — the scenes, details, and dialogue, that profoundly changed magazine and newspaper publishing. Cropping up all over the world were so-called “city” magazines that did their best to emulate New York magazine and capture its mojo. Even the New York Times tried by introducing a multitude of new sections into the newspaper with titles such as Styles, City, and Arts.

At the end of the book is a page dedicated to “magazines we’ve designed, redesigned, or consulted for” that lists some 100 titles, the majority of which no longer exist. New York magazine survives and still continues to strive for the New Journalism techniques of Felker’s era. But under the editorial leadership of Adam Moss, who was the longest-serving editor in the magazine’s history, from 2004 to earlier this year, when he was replaced by a digitally savvy 39-year-old, New York launched a series of digital landing sites with no discernible connection to the magazine — most notably Vulture, Grub Street, and Intelligencer.

In September, one of the largest and most successful digital-native publishers, Vox Media, announced that it had purchased New York magazine and its parent company. Even as far back as 2010, the veteran journalist David Carr, who died in 2015, would describe New York magazine as “fast becoming a digital enterprise with a magazine attached.”

On the very last page of the book is a small picture of Mr. Bernard and Mr. Glaser with a couple of colleagues goofing it up, and under it the caption reads, “We had fun indeed.”

We did, too, for years with those transportive, glossy things we held between our hands and which we called a magazine.

Walter Bernard, who has done design work for The Star, lives in Bridgehampton.