Robert Wilson, when receiving the Praemium Imperiale award in Tokyo, said to the audience, which included Hillary Clinton, “What artists do is one of the few things that will remain in time. As with the Greeks, the Romans, the Mayans, and the Native Americans, we see artifacts, the work of artists. When or if we go into the future thousands of years from now, we will be looking at the works of our contemporary artists.”

That ceremony was reported in The Star in 2023 by Richard Rutkowski, a cinematographer who knew and many years earlier had worked with Mr. Wilson. “Bob Wilson was another animal,” Mr. Rutkowski wrote, “and his dynamic thinking about past and future, their conflation, and his energy in the present made a truly deep impression.”

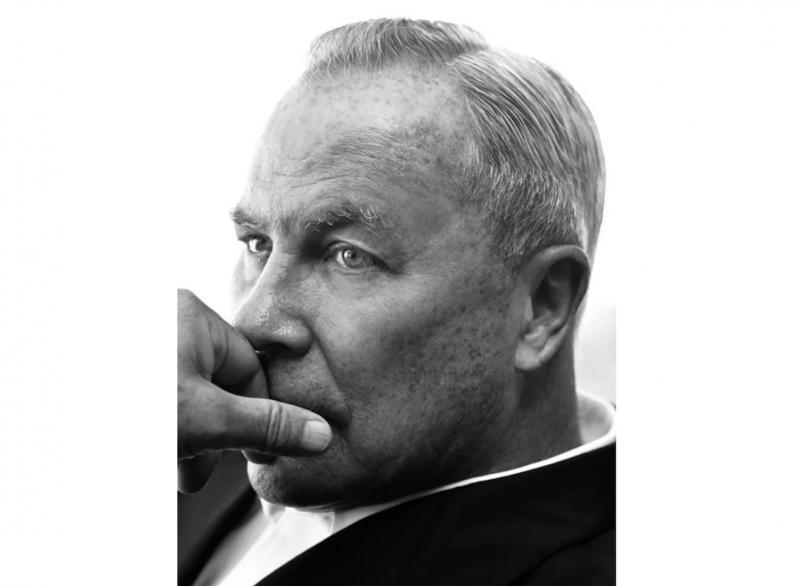

Robert Wilson died at home in Water Mill on July 31 after a brief illness. He was 83 and left behind not only a remarkable body of work as a theater director, playwright, and visual artist, but also the Watermill Center, a monument to his far-reaching vision.

He was born in Waco, Tex., on Oct. 1, 1941, to Diuguid Mims Wilson Jr., a lawyer, and the former Velma Loree Hamilton. He grew up in a conservative family, and was encouraged to enroll at the University of Texas in Austin to study business administration.

He dropped out in 1962 and moved to Brooklyn a year later, where he earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in architecture and interior design at Pratt Institute in 1965. After a brief and traumatic return to Texas, he came back to New York, rented a loft in SoHo, and founded the Byrd Hoffman School of Byrds, which was named after the dance teacher who helped him overcome a childhood stutter.

In 1968, while teaching acting and movement in New Jersey, Mr. Wilson witnessed an act of brutality between a policeman and Raymond Andrews, a young Black man who was deaf and mute. He intervened, accompanied Mr. Andrews to court, and ultimately adopted him.

Two years after his first major theater works, “The King of Spain” and “The Life and Times of Sigmund Freud,” both from 1969, he collaborated with Mr. Andrews, Andy de Groat, a choreographer, and Sheryl Sutton, a performer, to create “Deafman Glance,” a “silent opera” that relied more on visual storytelling than spoken text. In a New York Times review, Clive Barnes wrote, “Wilson could implode the minds of a new generation. His mind has a striding step to it.”

Mr. Wilson continued to work in opera during the 1970s, and in 1976 teamed up with Philip Glass, the composer, and Lucinda Childs, a choreographer, to create one of his most ground-breaking and enduring works, “Einstein on the Beach.” In a review of the opera’s 2012 revival at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Anthony Tommasini of The New York Times wrote, “Today, maybe more than ever, ‘Einstein’ comes across as an original, visionary, and generous work, anything but polemical.”

Mr. Wilson and Mr. Glass joined forces again in 1984 with “the CIVIL warS: a tree is best measured when it is down,” conceived as a 12-hour opera, though the full project was never realized.

Among Mr. Wilson’s many other collaborations were “The Black Rider: The Casting of the Magic Bullets” (1989), with Tom Waits and William S. Burroughs; Euripides’s “Alcestis” (1986), with Laurie Anderson; “Cosmopolitan Greetings” (1988), with Allen Ginsberg, and “The Old Woman” (2013), with Mikhail Baryshnikov and Willem Dafoe. He also worked with Lady Gaga, Brad Pitt, Winona Ryder, Renée Fleming, and Alan Cumming.

Congruent with his theater work was his fascination with chairs, as both a designer who integrated them into his productions and as a collector whose holdings surpass a thousand of them. His own creations have been exhibited and are held by museums, galleries, and private collectors, and he was recently represented in the Guild Hall exhibition “Functional Relationships: Artist-Made Furniture.”

Bearing in mind the scope of his artistic and theatrical accomplishments, it’s both surprising that he was also able to find the time to realize his vision for the Watermill Center, and yet, recalling Mr. Rutkowski’s admiration for his energy, maybe it isn’t.

The center opened in 1992 on the site of a former Western Union communication research facility in Water Mill. Mr. Wilson’s website calls it “a laboratory for performance,” and as such it offers residencies to artists and collectives to develop works that “challenge and extend the existing norms of artistic practice.”

Those residencies are suspended during July and August for the International Summer Program, which brings a diverse group of 60 to 100 artists from over 30 countries to observe Mr. Wilson’s performance methodologies.

The center also houses his extensive art collection for research and study, and a library whose 9,000 titles are available to researchers, artists, students, and visitors year round.

A quotation on Mr. Wilson’s website offers a succinct statement of his vision: “An artist recreates history, not like a historian, but as a poet. The artist takes the communal ideas and associations that surround the various gods of his or her time and plays with them, inventing another story for these mythic characters.”

Mr. Wilson is survived by his son, Mr. Andrews, a sister, Suzanne, and a niece, Lori Lambert. Memorials will be held in the near future at locations that were especially meaningful to him, according to his website.