On the Edge of History

On the Edge of History

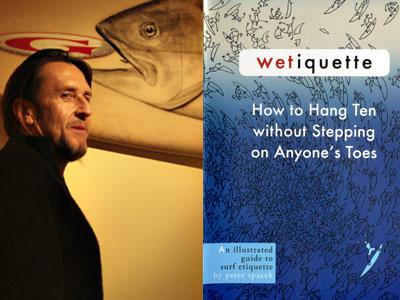

“Midnight in Europe”

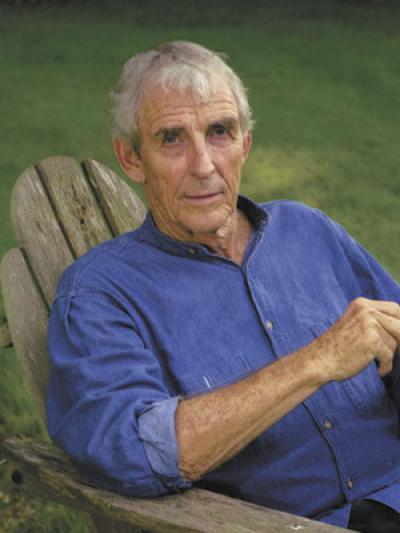

Alan Furst

Random House, $27

Nearly 75 years later, there are no doubt people who imagine that Europe suddenly awoke on a Sept. 2 morning and found itself at war (again), Germany having invaded Poland the day before. Logic and historians tell us, however, that World War II did not ignite spontaneously. It came after a long, ominous buildup and with a great deal of foreshadowing in the form of various struggles between republicanism and fascism — most notably the Spanish Civil War, waged between July 1936 and March 1939.

Such is the background, and the essence, of Alan Furst’s brand-new novel, “Midnight in Europe.” This eminently readable book provides glimpses into the history of a particular moment, as well as into the lives of people living on the edge, as it were, of that history. The result is a story of political intrigue combined with elements of romance, pathos, and a bit of humor. All told, it makes for an appealing tale.

At the center of the novel is Cristian Ferrar, an expatriate Spaniard living and working in Paris in 1937. The back story is that the Ferrar family had fled their homeland because they were republicans who felt endangered by Generalissimo Franco and his fascists, and that Cristian, a highly regarded young attorney at the international law firm Coudert Freres, supports an extended family consisting of his parents, his siblings, and his wise and lovable abuela (grandmother).

Early on, Cristian is approached by diplomats from the Spanish embassy in Paris, which represents the republicans, the duly elected Spanish government at the time. They request his participation in a clandestine organization that seeks to purchase armaments for the beleaguered republican forces. (A web of diplomatic treaties, agreements, and maneuvers by Hitler and his allies and appeasers has essentially isolated the Spanish Republic on the world stage, placing it in desperate straits that will eventually lead to its defeat by the fascists.)

Cristian obtains permission from the head of the Coudert firm to assist his country’s government (as long as doing so doesn’t take too much of his time and energy away from the office and his clients). He enters a dusky underworld of assorted odd characters and sometimes-seamy places. Along with Max de Lyon, a pseudonymous Jewish arms dealer who is hunted by the Gestapo, a Macedonian named Stavros (who grew up “fighting Bulgarian bandits. After that, being a gangster was easy”), and others, Cristian embarks on a trans-European odyssey aimed at sourcing, purchasing, and shipping badly needed arms for the Spanish republican army.

Among their more chilling encounters is when Cristian and Max are pulled off a train by officious officers of the German Reich. They save themselves by convincing the Nazis that they are salesman for a “naturist” magazine and distract their potential captors by showing them sample copies.

One of the more memorable scenes involves commandeering an entire train, by dark of night, in order to move an arms shipment that has been impounded in northern Poland.

This is a world in which anyone could be a spy, and often is.

In addition to the primary cloak-and-dagger plotline, there are other narrative threads involving seduction by (or of) a gorgeous Spanish marquesa, an ultimately comical family feud among Hungarian aristocrats, and Cristian’s growing sense that he must relocate his entire family to New York, fearing, with prescience, that Paris will soon be an unsafe haven for them. (In anticipation of such a move being necessary, he rents a four-bedroom apartment in a West End Avenue building — “airy, with high ceilings” — for $68 a month.)

The various story angles help fill out an overall sense of the time. Mr. Furst, who resided in Paris for many years, has a nuanced appreciation of the French capital and its inhabitants. (“Parisians found themselves restless and vaguely melancholy for no evident reason, an annual malady accompanying the nameless season that fell between winter and spring.”)

Moreover, the author evidences good research into the period. A Berlin hausfrau looks at her watch and swears. “Time for a Hitler speech. Greta, turn on the radio, good and loud.” She explains to her French visitors, “It’s the law, you must listen to the Fuehrer’s speeches. So those little bastards from the Hitler Youth patrol the streets — sneak around and listen at your windows. If they don’t hear Adolf, they report you and the Gestapo comes around.”

“Midnight in Europe” takes its place among Mr. Furst’s several other novels, which, as he has said, “follow the clandestine war between European spy services from the years 1933 to 1942, and their geography follows the reality of actual events.”

The most curious effect of this melding of fact and fiction is that the ending of the novel, in 1938, isn’t really an ending at all. Cristian Ferrar and the other characters may not fully understand, but as we know all too well, it’s actually only the beginning.

A weekend resident of East Hampton, James I. Lader regularly contributes book reviews to The Star.

Alan Furst lives in Sag Harbor. “Midnight in Europe” came out on Tuesday.