In Search of Heroes

In Search of Heroes

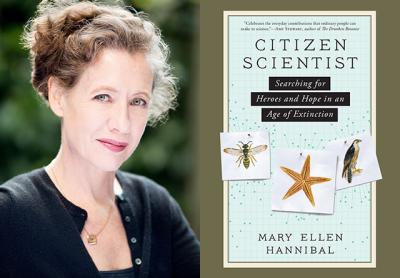

“Citizen Scientist”

Mary Ellen Hannibal

The Experiment, $25.95

“What we need to do is humanize the scientists and simonize the humanists,” C.P. Snow argued in his highly influential 1959 talk, “The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution,” which drew attention to the rift between the sciences and the humanities and sparked decades of contentious debate. Fifty-seven years later, obvious signs of this rift continue in the increasing specialization of academic scientific and humanistic inquiry, in the consequent separation of academic and public discourse, and in what some say is rising scientific and cultural illiteracy.

Yet, visible and encouraging signs of repair sprout and grow in many diverse places: STEM to STEAM projects that incorporate art into science, technology, and mathematics education, National Parks Service artists-in-residence programs that support poetry and art in parks, and a 2014 study in the journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics that analyzed painting from 1500 to 2000 for evidence of climate change, to name a few.

Mary Ellen Hannibal’s recent book, “Citizen Scientist: Searching for Heroes and Hope in an Age of Extinction,” takes readers on an epic journey that traverses the terrain where the sciences and humanities meet and where hope issues from dialogue between the public and specialists. She reveals the continuing importance of Snow’s argument as she illustrates the imperative for all of us, whether we are trained in the sciences or the humanities, whether we are professionals or amateurs, to use all of the tools — from science and art, psychology and literature, geology and music — available and to fashion new tools when necessary to stave off environmental catastrophe and preserve biodiversity.

Ms. Hannibal’s primary focus is the contributions of regular people, citizen scientists who volunteer their time to projects that generate data that scientists and other professionals use to try to effect change and preserve life on earth.

She begins with the work of Tim Morton, a philosopher who has made foundational contributions to the emerging field of posthumanism, an interdisciplinary movement that seeks to redefine human identity in the context of the anthropocene — the scientific name for our era, an era marked by unprecedented anthropogenic impact on the planet and all its inhabitants. This impact, Mr. Morton and other posthumanists argue, results not only from the material consequences of the Industrial Revolution but also from the ideological consequences of modernist ways of understanding that posit humans above other creatures. To respond to current environmental threats, we need to topple this artificial hierarchy.

Ms. Hannibal furthers the work of posthumanists by blending together literary and scientific traditions to create a humbling picture of the role of humans on the planet. Her work, which includes references to Carl Jung, Herman Melville, Ernest Hemingway, and many others, shows us how literature and myth as well as data collection and analysis are all essential to our understanding of ourselves, the physical worlds in which we live, our neighbors, and our relationships.

She raises interesting, important questions about how personal stories intersect with family stories, stories from literature, and the stories scientists piece together from data about changes in the natural world. Reading her book makes us consider how our experience of time is shaped by stories, how human experience of time intersects with, registers, and, ultimately, makes an impact upon geological time, and how this alters our understanding of ourselves and our responsibilities as global citizens.

Ms. Hannibal has a direct answer: Participate in citizen science. In doing so, we will not only be active participants in solutions to environmental problems, we will also be engaging in an activity that originated with the founding of democracy in the United States. A growing movement in the 21st century, citizen science was a crucial aspect of colonial American culture, an early yet oft-forgotten element of the construction of democracy, a project largely enabled by the work of colonial women, Native Americans, African slaves, and others who collected specimens that were sent to the Royal Society of London. Their efforts intimately connected scientific work with culture work.

Like any adventure story, Ms. Hannibal’s book includes a cast of characters. In this case, the characters fall into four categories: the author and her family, especially her father, Edward Hannibal, a writer and advertising executive; the teams of scientists whose professional work addresses climate change, habitat loss, and dwindling biodiversity; the citizen scientists whose volunteer contributions allow the scientists to document these changes, and the ecosystem itself, an entity whose fate is uncertain.

The parallels between Ms. Hannibal’s relationship with her dying father and habitat loss and species decline personalize and revitalize the story of environmental destruction — a story many have become inured to as we are oversaturated with information and emotional appeals.

In many ways, Ms. Hannibal’s exacting attention to detail amplifies her primary message of urgency and hope — the environmental crisis is manifest in a dizzying number of ways. Exponentially growing teams of amateurs and professionals are working to protect the planet. There are so many ways for us to get more involved, to be heroes, to create hope, to save our home — but, at times, I felt these details overwhelming.

Then I remembered the words of Immanuel Kant, the ethicist and theorist of the sublime, an 18th-century movement that attempted to articulate concepts that move us beyond conventions, who wrote in “The Critique of Pure Reason”: “Whereas the beautiful is limited, the sublime is limitless, so that the mind in the presence of the sublime, attempting to imagine what it cannot, has pain in the failure but pleasure in contemplating the immensity of the attempt.”

While Ms. Hannibal’s use of details verges on the sublime, her language — especially her descriptive writing — is unquestionably beautiful, and she punctuates her grave analysis with levity and humor that made me laugh out loud.

Ultimately, Ms. Hannibal reminds us that we are part of something bigger, that we can take concrete steps to preserve biodiversity and planetary health, that our individual work has collective effect, and that this really matters. For these reasons, “Citizen Scientist” is an important book. If we want to ensure the survival of its central character, we ought to heed Snow’s advice, come together, and engage in the projects Ms. Hannibal describes.

Stephanie Wade is assistant professor and director of writing at Unity College in Maine. She spends summers in East Hampton.

Mary Ellen Hannibal grew up in East Hampton. A past recipient of the National Association of Science Writers’ Science in Society Award, she lives in San Francisco.