A Literary Provocateur

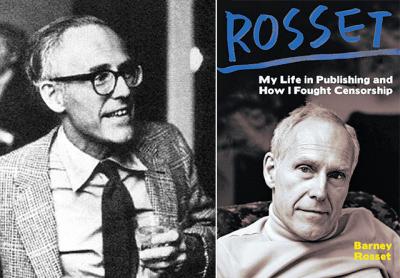

“Rosset”

Barney Rosset

OR Books, $28

If one were asked to name the cultural heroes of the last 100 years, chances are Barney Rosset would not be among the first to roll off the tongue. In point of fact, however, this American publisher and sometime movie producer fought nearly all of the major First Amendment battles of the second half of the 20th century. It may be that no single person has done more to knock down the doors of censorship in art and literature in America than Barney Rosset.

There’s no doubting Mr. Rosset’s taste in literature. Even the most modest bookcase will have at least a volume or two from Mr. Rosset’s highly influential publishing house, Grove Press, which he acquired in 1951. Judging from his memoir, however — “Rosset: My Life in Publishing and How I Fought Censorship” — his literary taste did not necessarily translate to literary talent. This memoir is mostly written in a declarative, perfunctory style that lacks the famous vim and vigor of its author. The flesh-and-blood Barney Rosset was by turns irascible, devilish, and highly mercurial, and it is head-scratching that this memoir only occasionally manifests that personality.

Nevertheless, the story recounted here is a colorful and important one. Mr. Rosset, who grew up in Chicago in between world wars, states that he was never as happy again as he was at the age of 17, when he was the class president, star in both football and track, and (already) a literary provocateur, drawing up a petition demanding the release of his hero, John Dillinger. During World War II he bluffed his way into the Army photographic unit, stationed in China. Following the war, he sank $250,000 of his family’s money into his first film, “Strange Victory,” a documentary that chronicled racial bias in the treatment of black war veterans. The film was a box-office disaster but cemented Mr. Rosset’s penchant for marrying financial risk with provocative subject matter.

There was the requisite stint in Paris, where Mr. Rosset met Joan Mitchell, the Abstract Expressionist painter, who became his first wife (there were five). She led him back to Greenwich Village, where he fell in with the Beats and the artists at the Cedar Tavern. It was during this time that Mr. Rosset bought the nearly defunct Grove Press (for $3,000!) and when things in his professional life started to get interesting. At Grove, Mr. Rosset published no less than Samuel Beckett, Jean Genet, Henry Miller, Harold Pinter, Eugene Ionesco, and Che Guevara, among others.

The first major censorship battle was over D.H. Lawrence’s “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” in 1957. It was deemed obscene and prompted the U.S. Postal Service to seize copies (the ruling was eventually overturned). Further battles were waged over Henry Miller’s “Tropic of Cancer,” William Burroughs’s “Naked Lunch,” and the film “I Am Curious (Yellow),” for which Mr. Rosset was the distributor. Ultimately, all of these cases broke Mr. Rosset’s way, and some with a huge payoff: “Tropic of Cancer,” for example, sold well over a million copies for Grove and made Mr. Rosset, and his publishing company, rich.

But fortune would not last for Mr. Rosset, whose finances rose and fell from year to year. It is interesting to note that at one point he owned more than 100 acres of prime land in East Hampton, only to sell off parcel after parcel to pay for each impending court battle. It is not an exaggeration to assert that the war over censorship in America was literally paid for with East Hampton real estate.

There are, of course, some tasty anecdotes in the book, including Mr. Rosset pulling a raging actor off Norman Mailer, and a number of very tender recollections of his friendship with Samuel Beckett, which lasted decades. In a rare moment of close observation in “Rosset,” the author remembers a breakfast in Paris with Beckett at which diners placed their orders by submitting cards with pictures of food on them.

“In a funny way, it was pure Beckett . . . you could choose a meal in total silence. In the same vein, Beckett had made increasing use of the stage directions ‘pause’ and ‘silence’ in his work, and had pared down his vocabulary with fewer and fewer words.”

Mostly, though, this is a memoir content to enumerate the varied accomplishments of its author in a flat, monochrome voice that is only occasionally roused. And there is a mother lode of publishing minutiae in “Rosset” that most readers will find esoteric: advances, units sold, book fairs, etc.

For all of its faults, however, this book does have a cumulative effect, leaving one in a state of admiration as you follow Mr. Rosset decade after decade in his dogged pursuit of artistic freedom. The book is at its best with its chapters on “Tropic of Cancer,” a novel Mr. Rosset loved intensely. He originally encountered it as a student at Swarthmore in 1940, where he read a smuggled copy. Though publishing it ultimately made him rich, the memoir leaves no doubt of the sincerity in his fight to see it legally published in America.

“. . . there arose from it an almost mystical feeling, a sense of the numinous, which grew stronger as the story went along. . . . Both Miller and Lawrence developed and communicated an intense, freeing belief that we should live the kind of life we desire — and they inspired each of us to believe and do the same.”

As this imperfect memoir reminds us, much the same could be said of Barney Rosset (who died in 2012). In a different kind of country, he might have won the Congressional Medal of Freedom. As it is, we have simply his legacy, one where the meaning of the word “obscene” — indeed the cultural landscape of America itself — was changed forever.

Kurt Wenzel’s novels include “Lit Life” and “Gotham Tragic.” He lives in Springs.