The Way We Live Now

The Way We Live Now

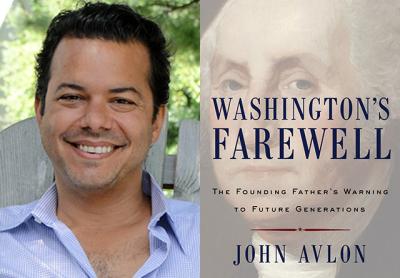

“Doctorow:

Collected Stories”

E.L. Doctorow

Random House, $30

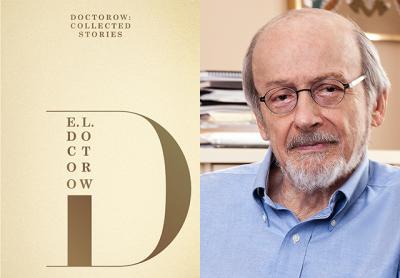

E.L. Doctorow is best known and admired for novels such as “Ragtime” and “The Book of Daniel,” in which he uses his imagination to alter and enrich factual events. People plucked from history — J.P. Morgan, Houdini, Emma Goldman, Freud, and Ethel and Julius Rosenberg among them — engage fictionally with one another, as well as with a fleet of invented characters. Asked by the editor Ted Solotaroff whether two of those real-life figures had ever actually met, as depicted in a scene in “Ragtime,” Mr. Doctorow replied, “Well, now they have.”

That kind of winning self-confidence is apparent not only in his novels, but also, it turns out, in his short stories.

The novels have notably strong political and social content, which might at first glance seem to be missing from the stories. “Willi,” which opens “Doctorow: Collected Stories,” is an intense account of sexual passion, obsession, and betrayal, culminating in an act of physical violence. The story is set at a nonspecific time in an unspecified rural place, ostensibly removed from the world at large, until the final two sentences. “This was in Galicia in the year 1910. All of it was to be destroyed anyway, even without me.”

A more blatantly political tale, tipped off in its title, “Child, Dead, in the Rose Garden,” was originally published in 2003, during George W. Bush’s administration, but it feels chillingly current. When the shrouded body of a small boy is found in the White House Rose Garden after a National Arts and Humanities function, paranoia and attack mode quickly set in. A White House liaison says, “Wouldn’t you think it figures, from this crowd, something disgusting like this? . . . Not that I ever expect the artists, the writers, to show gratitude to the country they live in. They’re all knee-jerk anti-Americans.”

The dead child can’t be immediately identified, but a consulting psychologist from the C.I.A. speculates, “This feels to me like an Arab thing,” before adding, “Then he could be from where they hate us. . . . He could be a Muslim kid.” Terrorism is on everyone’s mind, even after the suspected vest of explosives is ruled out. Instead, the asthmatic child wears a bronchodilator on a lanyard around his neck. Viewed on a lab table, the body’s “little chest was expanded, as if the kid was pretending to be Charles Atlas.” He’s dubbed P.K., for Posthumous Kid, by F.B.I. agents. Numerous people are detained and interrogated, deportation is threatened, and various cover-ups are invented.

The incident never happened. The abandoned body wasn’t a child, after all, but a rabid raccoon, requiring everyone (including the first dog) to be tested. And the elderly widowed groundskeeper who made the discovery in the Rose Garden may be suffering from dementia.

The nearly retired Special Agent B.W. Molloy is brought in to serve as the chief investigator of the case and the conscience of the story. As he methodically probes and scrutinizes, tracking down the identity of the body and who put it there and why, he also looks backward at his own career, and inward. Had he wasted his life? “Whatever his motives, it was a fact that he’d spent [it] contending with deviant behavior, and only occasionally wondering if some of it was not justifiable.”

The unraveling of the mystery of the dead child in the Rose Garden, in all its tragedy and complexity, becomes secondary to Molloy’s discoveries about himself.

The propulsively readable “Walter John Harmon,” concerning a cult led by a con artist (and former auto mechanic) who absconds with his worshipers’ funds, along with one of their wives, also seems eerily prophetic when it’s discovered that Harmon, who’d never wanted anything written down, had drawn up elaborate plans, before his departure, to build a wall around his community.

Among my personal favorites in this collection is “The Writer in the Family,” the first-person narration of a gifted adolescent boy named Jonathan, charged by relatives with writing letters to his paternal grandmother, purportedly from his recently dead father, so that she will not suffer the knowledge of his death. Caught between his destitute, embittered mother and his rich, imperious aunt — the perfectly titled “Frances of Westchester” — Jonathan obeys the latter, up to a point.

Precociously resourceful, he invents a new life in Arizona for his father, where he prospers as he never did in his actual life. His brother questions the necessity of the arrangement — “Does the situation really call for a literary composition? . . . Would the old lady know the difference if she was read the phone book?”

And their mother objects to this final manipulation of her late husband in the service of protecting her despised mother-in-law. “He can’t even die when he wants to!” she cries. “Even death comes second to Mama! What are they afraid of, the shock will kill her? Nothing can kill her. She’s indestructible! A stake through the heart couldn’t kill her!”

The pleasures of this story are myriad — the dark and often hilarious politics of family, the arc of the boy’s shifting loyalties, and, as in all of Mr. Doctorow’s work, the keen emotional insight. “I thought how stupid, and imperceptive, and self-centered I had been never to have understood while he was alive what my father’s dream for his life had been.” In his bold, final letter “from Arizona,” Jonathan attempts to ameliorate this harsh judgment of himself.

“Wakefield,” inspired by the Hawthorne story of the same name, but reset in modern suburbia, is another standout. Partly by accident and partly by design, a man finds himself living in the garage attic of his own home. From this hideout, he can, unobserved, observe his wife and children and contemplate his marriage. This is a popular, perhaps irresistible, premise among contemporary writers — Andrei Codrescu and Daniel Stern also wrote stories with the same title and similar theses.

In Mr. Doctorow’s version, Wakefield wonders, “What is there about a family that is so sacrosanct . . . that one should have to live in it for one’s whole life, however unrealized one’s life was?” He recalls infuriating, Cheever-like arguments with his wife, Diana, in which she addresses him by his surname (“one of her feminist adaptations of the locker-room style that I detested”). And he envisions her morphed into her own mother — “the widow Babs,” who opposed the marriage — in 30 years, “high-heeled, ceramicized, liposucted, devaricosed, her golden fall of hair as shiny and hard as peanut brittle.” Yet Wakefield also notes Diana’s enduring grace and beauty, declares his steadfast love for her, and, as the days and weeks go by, feels “despicably lonely.”

There are writerly gems throughout this collection. A grade-school teacher in “The Hunter” reads aloud to the residents of an old people’s home. “They sit there and listen to the story. They are the children’s faces in another time.” Later, the teacher poses with her young students for a class photo, “holding her hands in front of her, like an opera singer.” A music box in “Baby Wilson” plays “ ‘Columbia the Gem of the Ocean,’ as if anyone would want to hear it more than once.”

In “Jolene: A Life,” Phoenix is seen by the title character as “a hot, flat city of the desert, but with a lot of fast-moving people who lived inside their air-conditioning.” And the description, in the same story, of the “busyness” of an empty street at 3 in the morning, which reads like the literary caption for a Hopper painting, concludes, “It was the world going on as if people were the last thing it needed or wanted.”

A few complaints of redundancy have been made about this volume, because all of the included stories had been previously published, in varied assortments, in other collections, while others have been left out. But several of the stories here seem deeply interconnected by their reflections on the way we live now, in families and in society — most particularly regarding the urgent and contentious matters of immigration and assimilation.

A priest in “Child, Dead, in the Rose Garden” remarks cautiously about his congregation of immigrants, “They love their Blessed Virgin. But they are learning to be Americans.” In “Heist,” the peddlers on New York City streets “come over from Senegal, or up from the Caribbean, or from Lima, San Salvador, Oaxaca, and find a piece of sidewalk and go to work.” And in “Wakefield,” a group of scavengers at a Dumpster are seen, with admiration, as performing “entry-level work into the American dream.” There is even a story titled “Assimilation.”

According to the dust jacket copy, E.L. Doctorow — the writer in our national family — selected the contents of this compilation himself shortly before his death in 2015. Respect should be paid to his choices, even without an explanatory introduction, and, given the shelf life of most books — alleged to be somewhere between yogurt and cottage cheese — a new edition of work by a master of fiction is always welcome.

Hilma Wolitzer’s novels include “An Available Man” and “Summer Reading.” She and her husband live in Manhattan and were part-time residents of Springs for many years.

E.L. Doctorow lived part time in Sag Harbor.