Boy Wonder of the Silver Screen

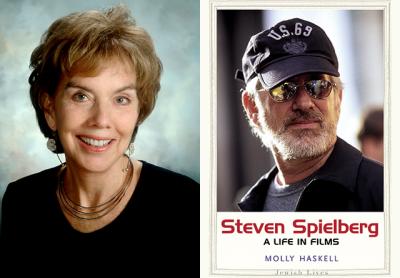

“Steven Spielberg:

A Life in Films”

Molly Haskell

Yale University Press, $25

That Steven Spielberg is a certifiable American genius is hardly a matter of debate. A shortlist of the films he has directed includes “E.T.,” “Jaws,” “Saving Private Ryan,” “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” and “Schindler’s List” — though there are 10 more “second tier” films one could name that are nearly as astonishing. There is an argument to be made that he is the greatest filmmaker in American history, surpassing even Orson Welles, John Ford, and Howard Hawks, and he may be the most naturally gifted director in the history of cinema.

You’d think such kudos would be enough for any writer to hang her hat on, but in Molly Haskell’s new minibiography of the director, titled “Steven Spielberg: A Life in Films,” she affords her subject all these superlatives and more. This compact, insightful — but at times overly gushy — biography often goes beyond hyperbole into the realm of hagiography. At one point she literally compares the director to God. The author’s conclusion at this contrast? Advantage Spielberg.

Ms. Haskell’s book does pull off a nifty trick, however, consolidating the life’s work of a prolific genius into a tidy 200 pages. Ms. Haskell breezes through Mr. Spielberg’s youth with a deft touch, hitting all the significant biographical flashpoints without getting bogged down in tiresome minutiae. She tells of the lonely boy with a workaholic father and a restless mother who was having an affair with a neighbor. Young Steven endures numerous phobias and anxieties, along with incidents of moderate to severe anti-Semitism.

Soon, though, Boy Wonder is given an 8-millimeter camera and discovers an uncanny facility. A subpar student, he nevertheless is able to enlist large contingents of teenagers from the neighborhood into ambitious amateur film productions, and a few of these are even shown at a local theater.

He arrives in Hollywood as a studio gopher, soaking in the atmosphere and chatting up anyone who will talk. (He also develops a long memory: Charlton Heston, who spurned the young Spielberg during this period, will later come knocking to play Indiana Jones. We know how that turned out.) He eventually starts working in television, directing episodes of “Night Gallery.” He falls in the with the “movie brats” of Malibu — Brian De Palma, John Milius, and, most significantly, George Lucas, with whom he would later collaborate.

Two early directing tours de force, “Duel” and “The Sugarland Express,” were mostly overlooked by audiences but legitimized Mr. Spielberg enough to get him hired for the helm of “Jaws.” From then on, he never looked back.

Ms. Haskell goes through Mr. Spielberg’s canon film by film, acutely assessing the financial and artistic merits of each and introducing biographical interpretations of some of the director’s imagery. Her theory is that Mr. Spielberg’s films are wrought with leitmotifs from his childhood longings and phobias. Most of these assertions are convincing, especially with Ms. Haskell’s take on “Poltergeist,” which particularly seems to resonate with some of the director’s more explicit childhood peccadilloes, such as his aversion to the swaying trees outside his bedroom window, and the sense that the family television was talking directly to him.

Not all this psychoanalyzing hits its mark, however, and there are times when it feels that Ms. Haskell is straining to connect dots that aren’t there. Early on, for example, the author explains how the young Steven felt (as do many Jewish children) that he was missing out on the holiday of Christmas. Later, she tries to connect this to some of his more iconic imagery.

“Consider the otherworldly savior E.T. The blinding light at the door in ‘Close Encounters of the Third Kind.’ What is this sound and light show, this ethereal song, this luminous ship from outer space but a Jewish child’s fantasy of Christmas?”

That sure seems like a stretch, and the hopped-up language doesn’t make it any truer.

And the author’s suggestion of Mr. Spielberg’s omnipotence is a little much. In her introduction, she recounts her subject’s double duty as director of “Schindler’s List” by day and editor of “Jurassic Park” by night: “The juxtaposition — as if dread and anxiety could thus be halved, one film allaying the stress of the other — seems almost inhuman as well as superhuman.”

Later the author states that Mr. Spielberg has “touched more lives and boosted more careers than the Almighty. . . .” I was ready to take this as irony until it was echoed in a later chapter on “Jaws.” There she recounts, with off-putting esteem, how two youngsters lost their arms to sharks just before the 2015 re-release of “Jaws.” “Once again Mr. Spielberg had surpassed God in his mastery of mis-en-scene.” Rarrr. Down, girl.

Better is Ms. Haskell in identifying the director’s failure to create a single memorable female character and his inability to invoke romantic or erotic love in any of his films. The female characters, especially in Mr. Spielberg’s earlier work, tend to be tomboys or shrills (think Karen Allen in “Raiders” or Kate Capshaw in “Temple of Doom”), and there is not a romantic comedy in his oeuvre.

She is also not averse to hinting at a touch of greed in her subject, recounting how after the success of “E.T.,” the director was raking in a million dollars a day but still felt the need to produce movies like “Gremlins” and “The Goonies,” both of which seemed like nothing more than cash cows. (In the next two years, incidentally, audiences will be treated to “Raiders of the Lost Ark 5” and “Jurassic Park I’ve Lost Count.”)

So no, Mr. Spielberg is not God, though his talent is, at times, an awesome thing to behold. I wish Ms. Haskell’s biography, slim as it is, explained exactly how this talent works — or at least tried to. What is it like to work with Mr. Spielberg? What makes him so adept with actors? How does he elicit such great performances? The author doesn’t seem particularly interested in these questions, more content to deify her subject and his abilities as something otherworldly.

For readers who don’t share this curiosity, however, “Steven Spielberg: A Life in Films” will satisfy as a keen, if cursory, overview of one of the most gifted practitioners in the history of American entertainment.

Kurt Wenzel is a novelist and a regular book and theater reviewer for The Star. He lives in Springs.

Steven Spielberg has a house in East Hampton.