Words of Solace

Words of Solace

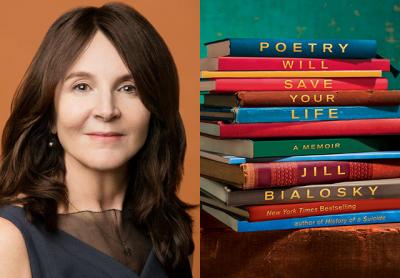

“Poetry Will Save

Your Life”

Jill Bialosky

Atria Books, $24

In 1939, W.H. Auden famously asserted that “poetry makes nothing happen.” Jill Bialosky seems to offers a diametrically opposing view in her unusual and affecting new memoir. Using 51 poems, ranging broadly from nursery rhymes to a Shakespeare sonnet, she sets out to demonstrate how reading and remembering poetry can provide a kind of salvation.

The informing, seismic event of Ms. Bialosky’s childhood was the sudden death of her father when she was 2 years old. There were subsequent aftershocks: her mother’s active dating life and her remarriage to someone fifth-grader Jill and her two sisters had never met; the birth of another sister; the faltering and eventual dissolution of that second marriage, followed by her mother’s retreat into depression.

All of these incidents were out of Ms. Bialosky’s control, yet she identifies strongly with Robert Frost’s “The Road Not Taken,” the poem that commits her to a love of poetry when it’s read aloud by her teacher. She sees her own story in it.

“There are two roads one might travel: The road where families are whole and not broken, and fathers don’t die young, and mothers are happy — where everything seems to fit together like pieces in a puzzle; and the road I travel, which is crooked and not quite right, with bumps along the way.” Of course she can’t change the past, but she looks to the future, to choosing the right path — in effect, to the power of autonomy. She quotes Frost: “Poetry is a way of taking life by the throat.”

The narrative of “Poetry Will Save Your Life” moves back and forth in time in the present tense (which enhances its fluidity) between the writer’s youth and her adulthood, with the touchstone of beloved poems as a constant. In one chapter she’s contentedly married, a burgeoning poet and editor; in another she’s still single and lonely, anxiously seeking love and purpose. In both circumstances, she’s instructed and consoled by lines of passion and despair by, among others, Louise Bogan, Gerald Stern, Denis Johnson, Sharon Olds, and Sylvia Plath.

And then there’s the discovery of Emily Dickinson, whose works make Ms. Bialosky “feel smart to think I understand them,” although the poems she cites, “After great pain, a formal feeling comes,” with its crushing line “This is the Hour of Lead,” and “ ‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers,” clearly reflect her own tenuous passage from grief to happy possibility.

As a self-conscious, fearful, and introspective girl, Jill Bialosky claims books as her “secret companions.” The characters in favorite novels “inform my envy, my empathy, my courage, my consciousness.” She relates easily to Louisa May Alcott’s “Little Women,” whose heroines grow up in an all-female household, and to the concentration on mothers and daughters in “Pride and Prejudice.”

It’s not surprising that she feels a similar shock of recognition on reading Dickinson’s playful “I’m Nobody! Who are you?” and poems of self-realization by Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Louis Stevenson. Bishop’s “In the Waiting Room” brilliantly recounts her own first awareness of the dichotomy of separateness and belonging. “But I felt: you are an I, / you are an Elizabeth, / you are one of them.” And Stevenson’s “The Swing” “recalls that same frightful realization of one’s own solitary self, sailing over the lip of the horizon ‘up in the air and down.’ ”

Ms. Bialosky suffered major losses as an adult, which must have reignited the pain of that first catastrophic loss, the death of her father. Two pregnancies resulted in the stillbirth of a daughter and the death of a premature son. And her cherished youngest sister, Kim — who she helped raise in a fatherless home during their mother’s emotional absence — committed suicide in her 21st year, a tragedy related in an earlier memoir, “History of a Suicide: My Sister’s Unfinished Life.”

Again and again, poems come to mind, offering their shared experience of bereavement, and their words of solace: Ben Jonson’s “On My First Son,” which opens “Farewell, thou child of my right hand, and joy”; Auden’s “Funeral Blues,” which orders: “Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone,” and, inevitably, Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art,” about enduring and mastering loss. Poetry and daily ritual help to mitigate grief, but, we’re told, “Eventually I find comfort in the idea that there are no clear answers.”

When Ms. Bialosky and her husband finally bring home a living child, a baby boy, they’re unprepared, without a crib or even a diaper — “We are still living in the aftermath of ravaged promise.” Feeling “selfish and voracious,” she wants to be her child’s only caretaker. Yet, “My psyche will not quite allow itself to feel the happiness and love that is flooding through every cell of my body. I keep expecting something terrible to happen.”

She compares herself to the narrator of Plath’s “Nick and the Candlestick,” which begins, “I am a miner. The light burns blue.” Ms. Bialosky writes: “Like the speaker in this magical poem . . . I am a miner excavating a rich new world, but always now with hesitation and awareness of life’s fragility.”

There are chapters in this book dealing with friendship, memory, shame, faith, danger, and mortality, and each subject becomes a part of the author’s own history, deftly illuminated by particular poems. Gwendolyn Brooks’s “We Real Cool,” which we are advised “should be taped on the refrigerator of every house with a teenager,” reminds Ms. Bialosky “with its nod to the rhythms of the street” and its devastating last line, “We / Die soon,” of jumping rope with her best friend, Marie (a future suicide), to the hypnotically repetitive verses of “Miss Mary Mack,” and “of all the perils and vulnerability that growing up held.”

During the recitation of the 23rd Psalm at her grandmother’s graveside, “I think of my father in his dwelling place and his mother, my grandmother, now with him,” she writes, “and that one day I too will be dwelling in the house of the Lord forever.” She wonders if the psalm may be only a “myth of consolation,” but concludes that it is sustaining nevertheless, and that poems may be the same as prayers.

Poems about fathers have special importance to Ms. Bialosky, and “Those Winter Sundays” by Robert Hayden “evokes memories and reverberations of the complicated ‘austere and lonely offices’ of a collective childhood, whether rich or poor, where a father wields his tender and cruel power.”

Two poems about mothers stand out as well: “My Mother’s Feet” by Stanley Plumly (who was Ms. Bialosky’s teacher) and Lucille Clifton’s “Fury.” The former is a love letter from the poet-son to his mother, and the latter a “scalding” depiction of a woman’s ambition and sacrifice. Ms. Bialosky’s earlier ambivalence toward her own mother seems to be contained in this pair of poems. We learn from her narrative how beautiful her mother, now in her mid-80s and living in a care home, still is, and that her daughter has come to terms with past difficulties between them, and with their current reversal of roles. “Now I am my mother’s keeper. . . . As once my life depended on her, now hers depends on me.”

Two additional poems are rendered to illustrate this familiar phenomenon: Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “The Child Is Father to the Man” and Wordsworth’s “My Heart Leaps Up,” from which Hopkins borrowed his poem’s title.

Auden’s words “For poetry makes nothing happen” are from his poem “In Memory of W.B. Yeats.” That line is preceded by “Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry. / Now Ireland has her madness and her weather still.” The madness Auden refers to is political strife. When Ms. Bialosky boldly declares that poetry will save your life, her meaning is more personal. “We’re all born mortal. We have to contend with the idea of mortality.” The closing of her own poem “Terminal Tower” (not included here) tells us, “I saw through the stone into the abyss. It was dark and splendid.”

Like the weather and politics, the human condition isn’t altered by poetry, but this lovely memoir poignantly and credibly shows how it can inspire our acceptance of it.

Hilma Wolitzer’s novels include “An Available Man” and “The Doctor’s Daughter.” Her poems have appeared in New Letters, Ploughshares, and Prairie Schooner. She and her husband were part-time residents of Springs for many years.

Jill Bialosky, an editor at W.W. Norton, lives in Manhattan and Bridgehampton. She will read from her new book at BookHampton in East Hampton on Friday, Aug. 25, at 5 p.m.