A Singular Pioneer

A Singular Pioneer

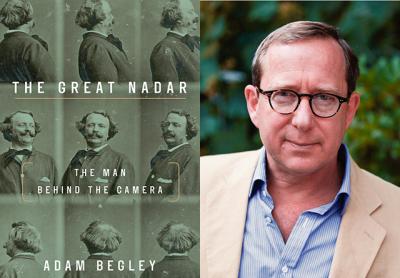

“The Great Nadar”

Adam Begley

Tim Duggan Books, $28

The title of Adam Begley’s amiable and readable new biography, “The Great Nadar: The Man Behind the Camera,” might provoke a couple of questions. The first is “Who?” Nadar (the nom de plume of a 19th-century Parisian photographer, writer, illustrator, and balloonist christened Félix Tournachon) may or may not be familiar throughout France, but he’s hardly Monet or Victor Hugo.

And “Great” in what ways? As an artist or, as the title suggests, as a showman? He seems to have been both.

As to his artistic merit, you can decide on the basis of the dozens of his photographic portraits, and a wealth of accompanying testimony from his contemporaries, that Mr. Begley presents. He had a large, enthusiastically reviewed one-man show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1994, so obviously there is something in his work to respect and admire, but how much of his success while he lived was due to his skill and talent and how much to the novelty of photography itself is a moot question.

He had the largest photographic studio in Paris, and his subjects included everyone of note in French culture — writers like Baudelaire, George Sand, Dumas, and Hugo; the actress Sarah Bernhardt; the artists Gustave Doré and Daumier, and hundreds of others. But whether he truly succeeded in capturing “in every portrait an intimate and compelling psychological likeness,” as Mr. Begley claims, is a matter of individual judgment.

In my own judgment, several of his studies are truly haunting and fascinating — portraits of Baudelaire, of his mother as she lay dying, of the poet Théophile Gautier, of the gorgeous Bernhardt at 20, and (my favorite, but unaccountably absent from the book) a full-length view of Victor Hugo at his desk that embodies the essence of the writer’s power and conviction.

Other pictures, though, seem run-of-the-mill. In his defense, Nadar was practicing an art in its infancy; cameras themselves were clumsy affairs, and the process of recording images involved dipping plates in a witches’ brew of chemicals and exposing them for relatively long periods of time, during which the subject had to remain immobile. It isn’t surprising, then, that some of them came out looking more like Mme. Tussaud’s waxworks than living people. Whatever spontaneity and psychological acuteness these pictures reveal may be due as much to the sitters’ ability to retain some natural expression of face and body as to Nadar’s talent in posing and capturing them.

And he wasn’t above fudging the details: When he photographed George Sand, no longer young and never beautiful, he obligingly retouched the work at her request, removing some of the wrinkles and chins. The movie actress Anna Magnani understood better than Sand or Nadar how a face acquires character and mirrors the psyche; she told her makeup artist on “The Rose Tattoo,” “Please don’t retouch my wrinkles; it took me my whole life to earn them.”

Mr. Begley seems, at times, too heavily invested in Nadar, too eager to establish his credentials as a worthwhile biographical subject. He claims, of his “extraordinary hero,” that “proof of his genius, the portraits are his own ticket to the pantheon of great artists.” But if you spend the word “genius” on Nadar, what’s left for Diane Arbus, Annie Leibovitz, Yousuf Karsh, Richard Avedon, or Henri Cartier-Bresson?

There was more to Nadar’s résumé than his picture taking, though. For several periods in his life, he left the business in the hands first of his brother, Adrien, and later of his son, Paul. At 20, Nadar was a penniless Bohemian, homeless and often hungry, but he had a flair for writing, and became a highly successful journalist, producing short, gossipy pieces called feuilletons that appeared regularly in widely read newspapers — blogs, in effect.

Nadar also had a knack for illustration and began to produce satirical political cartoons to accompany his writings in an inimitable and original style. Looking at his wickedly accurate caricatures with their accompanying texts, you could claim him as the inventor of the political cartoon, prefiguring Thomas Nast and Gary Trudeau, and even of the comic strip, in the vein of Jules Feiffer or Art Spiegelman.

And as if all this weren’t enough, he was a pioneer in the new craze for ballooning. Committing oneself to a voyage of unknown duration and destination, riding in a wicker basket under a bag filled with flammable gas, was both a stunt for daredevils and a path to new technologies of travel. In this, Nadar was almost clairvoyant: Despite his commitment to balloons, he believed, correctly, that the future of air travel was in flying machines that could be guided easily and landed safely.

With Jules Verne and others, he founded the Society for the Promotion of Heavier-Than-Air Locomotion, and in 1863 Nadar announced, “It’s the propeller — the sainted Propeller! — that will carry us into the air.” And so it was.

All this was decades before the Wright Brothers, of course, so those who wished to soar with Nadar had to be content with the balloon, which, once aloft, was at the mercy of the elements; winds could carry it out to sea or smash it to earth. With characteristic bravura and a keen taste for spectacle, Nadar built the largest balloon in the world, the accurately named Le Geánt, which boasted a wine cellar and a lavatory.

Its maiden voyage was a comedy of errors. Its second almost ended in tragedy: As it quickly climbed, its pilot released too much gas and it plummeted earthward. A gale was blowing on the surface, and the gondola in which the passengers rode bounced along “like a crazed comet,” as Nadar described it, narrowly missing a train, spilling its passengers out, and at last coming to rest in a grove of trees. The nine voyagers, including Nadar and his wife, suffered various degrees of injury, but no one, miraculously, was killed.

Chastened, he nonetheless persisted in ballooning, and when Paris was besieged during the Franco-Prussian War, he organized a complicated scheme whereby balloons were used to observe the enemy from a safe height, and the intelligence gathered sent back via carrier pigeon.

Nadar’s last years (and they were many; he was born in 1820 and died in 1910) were comparatively uneventful. He lived to see the invention of the airplane, of course, and before his death, the incomparable Jacques-Henri Lartigue was documenting his own life and times through photographs that are truly breathtaking.

But Nadar deserves his place in history. Mr. Begley shows that he did us the great service of illustrating, in several mediums, and in his multifaceted and theatrical way of living, a century that was like no other in its artistic and scientific accomplishments, particularly in France. And Mr. Begley deserves our thanks for bringing this singular pioneer to our notice.

Richard Horwich taught literature at Brooklyn College and New York University. He lives in East Hampton.

Adam Begley is the author of the biography “Updike.” A former writer at The Star, he is a regular visitor to Sagaponack, where his parents have a house.