Composer Seeks Silence in Gansett Dunes

Composer Seeks Silence in Gansett Dunes

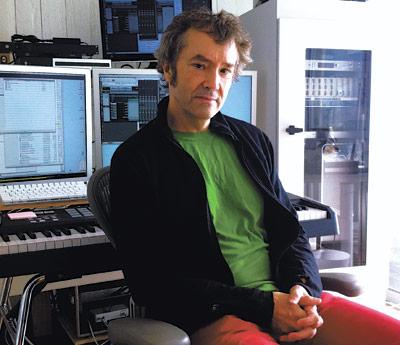

Carter Burwell chalks up his career to a series of fortunate accidents. Formally trained as a computer scientist, he studied animation and electronic music at Harvard, then wended his way to Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, where he was the chief computer scientist for a few years. He has gone on — somewhat to his own surprise — to score more than 80 motion pictures, ranging from box-office biggies (“Twilight,” “Rob Roy,” “True Grit,” “Fargo”) to cult classics (“The Big Lebowski,” “Being John Malkovich,” “Gods and Monsters”) to darker works (“Howl,” “No Country For Old Men”).

His latest studio project is the next installment in the teen-heartthrob phenomenon of “Twilight,” a cinematic juggernaut that continues with the Nov. 18 release of “Twilight: Breaking Dawn Part 1.” Being hired to write the score for a sure-thing blockbuster is testament to Mr. Burwell’s immense success — although he says he is still downright surprised to be even making a living as a composer.

“Around 1983, a bass player I knew was also a sound editor for movies, and he knew some of the bands I played in and the instrumental pieces that I wrote for this band, which were sort of moody,” he told The Star in a recent interview. “He knew the Coen brothers, who called me, and I went over and met with them. I was hired to work on ‘Blood Simple,’ their first film. They were just out of college, I guess we all were. I didn’t think I was embarking on a career. I thought, ‘This would be something different to do.’ ”

The Coen brothers — whose extreme honesty Mr. Burwell found endearing — explained that he shouldn’t expect to get paid for his work. “We were all surprised when it got distributed. And then people started calling me, and I realized that scoring was more instantaneous and emotionally satisfying than animation.”

The rest, as they say, is history.

Mr. Burwell often works with influential but rather experimental or edgy directors like Spike Jonze, who allow him the freedom to create unique aural experiences on “Being John Malkovich” and “Where the Wild Things Are.”

“Sometimes, directors have a very specific thing in mind and, honestly, it’s not that fun for me if they know exactly what they want,” Mr. Burwell said. “Some of the best directors — like Stanley Kubrick or Scorsese or Michael Mann — [are] all directors whose films I love to see [but that] doesn’t necessarily mean it would be fun to work on.”

Mr. Burwell moved to Amagansett a little over a year ago; he now lives in a contemporary house perched on the edge of the ocean, a weathered gray affair filled with the colorful and comforting chaos of family life. His studio is also there.

Mr. Burwell said that he had tested the waters of several coastal towns throughout the United States, including in Northern and Southern California, but had always avoided the East End because of its reputation as an elitist “social scene.” He expected Amagansett to be the very antithesis of the silent and beautiful landscape he had been seeking, but he discovered it there.

He has found a new serenity in his surroundings. But, he said, with it comes a certain level of concern among colleagues about his mental health. “Living in New York made me an eccentric composer, but living in Amagansett . . . it’s obvious I’m mad,” he said with a laugh. “People want to be able to drop by a couple times a week. And living here, that’s not really possible. The Hollywood studios are not comfortable being so far away. They worry it’s going to get out of control, that money is going to be wasted in some way, and they won’t know about it until it’s too late. People only come to me if they know they really want me.”

Mr. Burwell’s power was knocked out by the winds of Irene, just as he was in the final throes of his score for the latest “Twilight” movie. He was racing to meet a deadline that called for him to compose more than 80 minutes of music in just nine weeks, the time usually allotted to writing 40 minutes’ worth. It was an unprecedented test of his imagination and stamina.

“The hurricane was interesting,” he said with a sigh, shaking his head. “I was hoping that maybe the power wouldn’t go out at all, but the day it went out, I worked on my piano with an oil lamp the way they would have 100 years ago. Then I worked plugged into my car’s cigarette lighter with my engine running. Then I worked in the neighbors’ kitchen, and finally I ran an extension cord from my neighbors’ generator to my house, but realized an extension cord wasn’t going to do it for me. I had to get on a plane to Abbey Road in London to record in two days, so I gave up and took the Jitney to the city. I just got back a few days ago, and I’m starting to feel more like a human.”

Mr. Burwell said that his own world-view is rather more ironic than that of Bella and Edward and their vampire pot- boiler “Twilight” chums. The involvement of the director Catherine Hardwicke is what convinced him to become involved in the first “Twilight” movie, released in 2008, and the director of the latest installment, Bill Condon, has convinced him to sign up again.

“Everything said and done is from the heart,” Mr. Burwell said of the series. “I understand that concept, but it’s not the way I write or see the world. If she wasn’t directing it, I wouldn’t have gone for it [in hte first place].”

Mr. Burwell is also slated to do the second part of “Twilight: Breaking Dawn,” which will open in November of 2012. His “Twilight” years have brought him the most financial security he has ever known. Still, if he had his druthers, and could work in any genre, he would love the chance to do the score for a retro-flavored science-fiction film, something he has never done before. It would be the ideal coupling of his early studies in electronic and synthesized music and his hard-earned chops as an orchestral composer.

Mr. Burwell spoke about the science-fiction B-movies that entertained audiences for decades, before the big-bucks smash “Star Wars” swept majestically onto the screen.

“I’ve always been fond of science fiction,” he said. “And no one has ever asked me to do it. People don’t make those kinds of films anymore. ‘Forbidden Planet’ had an entirely electronic score before synthesizers even existed, they built their own circuitry. There was a tradition of pushing the boundaries of what constitutes a film score. That has been lost, and I really wish someone would ask me to write one.”

Mr. Burwell participated for the first time last year in the Hamptons International Film Festival, taking a seat on the jury judging narrative features. He’ll be pitching in again this week, by presenting a talk at Rowdy Hall in East Hampton on Friday morning at 10; the discussion is expected to range from his early musical inspirations to his collaborations with legendary directors. He’ll also show clips of some of the films he’s worked on, including “The Kids Are All Right,” “True Grit,” and “Fargo.”

“I’m happy to contribute in any way I can to cinema events out here,” he wrote in an email, “so I quickly agreed to do the panel, and the fact that it’s in a bar only sweetens the deal. Frankly I’m more interested in a dialogue than a monologue, so I’m hoping for good tough questions like, ‘Why the hell did you do that?’ ”