Long Island Books: Happy-Go-Lucky Guy

Long Island Books: Happy-Go-Lucky Guy

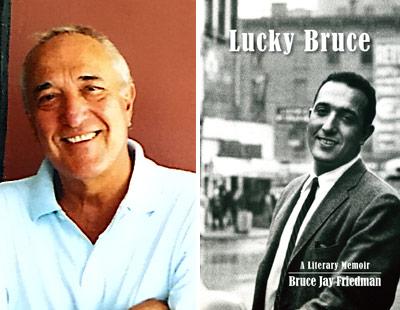

Spoiler alert: At the end of this picaresque romp, “Lucky Bruce,” the author, playwright, and screenwriter Bruce Jay Friedman (author of “Stern” and “The Lonely Guy’s Book of Life” and screenwriter of “Splash”) admits: “And always — no matter how weak the knees and frail the bank account — there has been the pleasure at Customs of filling in the blank for Occupation with the single word that has always felt treasured and benighted: writer.”

“Lucky Bruce”

Bruce Jay Friedman

Biblioasis, $26.95

So here’s where the adventure begins. Mr. Friedman studied journalism at the University of Missouri, which he says consisted of “memorizing the names of turn-of-the-century farming weeklies.” He maintains that his only literary effort by the end of college was a freshman essay on Hemingway and the Lost Generation. Mr. Freidman joined the Air Force during the Korean War and soon found himself on the staff of Air Training magazine, edited by a lanky, Southern, bookish pilot who was a New Yorker devotee. One day Mr. Friedman decided to try his hand at a short story. He mailed it in to the venerable magazine. It was plucked out of the slush pile and an editor wrote him an encouraging letter. Mr. Friedman wrote a second short story. Soon after, he received a letter: “All of us here are delighted with your story. . . .” The New Yorker published it. Talk about lucky. And hard-working.

Mr. Friedman offers four major backdrops in this book: the Beverly Hills Hotel’s swimming pool, the now sadly departed Elaine’s (his accountant once asked how he could possibly spend $18,000 per annum on veal piccata), the offices of a magazine group, and Water Mill here on the East End.

Bruce Jay Friedman first began honing his skills, while also supporting his family, as an editor at that group, called Magazine Management, a company that published teaser magazines in the ’50s and ’60s. One of the magazines he worked at was called Swank. His boss’s main job seemed to be the careful airbrushing of nipple aureoles out of photographs. Ironically, it was an excellent training ground. One of Mr. Friedman’s hires was a then-unknown Mario Puzo. After “The Godfather” came out, Puzo told interviewers that he learned the craft of storytelling at Magazine Management.

Mr. Friedman starts this book by telling the story of one of his first screenplays, “Stir Crazy,” starring Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder. The year was 1980. Vincent Canby’s review in The New York Times stank. Mr. Friedman was, understandably, depressed. What he really wanted to do was “bury the body.” But something compelled him to hail a New York City cab and go to a movie theater to see the mess. Problem was that at one cinema after another the tickets were sold out. “That was odd,” he writes. “Probably a benefit of some kind.”

The same cab driver kept driving. Same response at other theaters. When Mr. Friedman got in touch with one of his sons, the report was: “Dad . . . people who couldn’t get tickets were rioting and breaking down the police barriers.” The bomb that Mr. Friedman thought he’d written turned out to be the biggest grossing comedy that Columbia had ever released.

Yet he’s a bit embarrassed — all right, almost apologetic — about his Hollywood successes. And so he found himself bouncing back and forth between Hollywood and Elaine’s. The movie money was seductive, but his siren was the New York literary world. Along the way he hangs out with Kurt Vonnegut, Joseph Heller, Speed Vogel, James Salter, and Puzo, to name just a few.

He writes of Elaine’s restaurant as the Eden for writers. (Yes, I’m mixing plenty of metaphors here.) It was the watering hole where Gay Talese, Tom Wolfe, Woody Allen, and other writers hung out — some famous, some not so. And then there was Elaine herself — seemingly all steely business. She didn’t suffer fools gladly. But often when people paid in cash, the bills found their way into her décolleté and when a writer needed it, she could bail him out. Mr. Friedman writes charmingly of the night when someone asked for directions to the lavatory and she said, “Take a right at Michael Caine.”

He relates the story of Norman Mailer’s date once complaining about the lighting at Elaine’s. The proprietor “belly-bumped” the young woman out onto the sidewalk. Mailer took offense and wrote Elaine a long, angry letter. Elaine’s response? “Boring, Norman!” He came back to the fold.

In true picaresque style, few characters are developed in this book. But that makes sense: There’s just too much ground to cover in too short a time. Mr. Friedman notes the dissolution of his first marriage in a classy way, but we’re left to puzzle over what happened. He writes about his longtime marriage to his second wife, Pat, in darling terms — she’s the love of his life, he admits — and this was the fellow who wrote “The Lonely Guy” books before he met her. But we’d love to see her center stage just a bit more. This is a guy who, while he was working on the film “The Owl and the Pussycat,” had Natalie Wood — at the height of her career and between marriages to Robert Wagner — as his secretary! (A producer arranged it. Yes, there was a little nooky involved — but not too much.)

On the other hand he doesn’t have a mean thing to say about anyone — and it’s a relief that after such a long, fruitful career he doesn’t feel the need to do any score settling. He has a great many huge financial coups, but seemingly the money disappears — okay, that tab for Elaine’s veal over all those years was pretty hefty. (Mario Puzo once puckishly advised him not to mention that he had to sell a horse during one reversal.) Mr. Friedman’s even cheerful when he learns that all of his income is going to his ex-wife.

Along the way he frets that he wasn’t really being taken seriously. He’s also very funny on the subject of writerly jealousies. Once he attended a party at Norman Mailer’s house. At the time, Mr. Friedman’s play “Scuba Duba” was on Broadway, where it stayed for several years, playing to packed audiences. Mailer circled Mr. Friedman calling out: “ ‘Scuba Duba’ sucks!” Mailer’s play “The Deer Park” had just received lousy notices. Yes, punches were thrown.

The photos in the book are charming. Bruce Jay had to fight against type: He’s a tall, handsome, strapping fellow, shy, self-deprecating in a world of egotistical self-aggrandizers. This book is a true testament to decades of hard work, of perseverance. He may have been a lonely guy for a while — he tells us a little bit about affairs he had between marriages — and there were the times when he took a woman into the Magazine Management boss’s office after hours for hanky-panky, but on the whole Mr. Friedman comes across as a wholly decent, nice fellow.

In true Don Quixote fashion he’s fascinated by everything going on around him. Everything is an adventure. But seen through a kaleidoscopic lens. When the head of the English department at York College, where he was about to teach, took him to meet his colleagues, he announced: “Friedman here is our new irony man.” As Mr. Friedman’s agent Candida Donadio once said: “You have a crazy head.”

Oh, and all that revelation at the beginning of this review? You knew all along that was no real spoiler alert. This review began with the end, and so now it’s going to end with the beginning of “Lucky Bruce,” which opens with the following scene:

EXT. An apartment building in the Bronx. 1947.

Two mothers meet.

MRS. GIBSON: I’m so excited. My son Richie is off to study medicine at Kentucky.

MRS. FRIEDMAN: Congratulations.

MRS. GIBSON: What about Bruce?

MRS. FRIEDMAN: He’s going to be a writer.

MRS. GIBSON: (considers, shrugs) Oh well, we can’t always get what we want.

Mr. Friedman writes that when his mother lay dying, she puffed a Chesterfield and announced: “Don’t have any sympathy for me, darling. I’ve had my fun.”

Not only was Mrs. Friedman’s son lucky. He got what he wanted, and this memoir makes it clear that he’s also having plenty of fun.

—

Laura Wells is a writer and editor who lives in Sag Harbor.