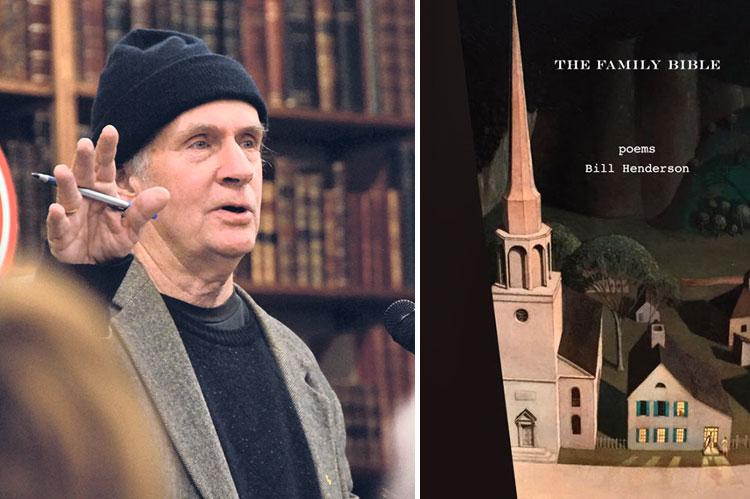

“The Family Bible”

Bill Henderson

Black Mountain Press, $22.50

A number of years ago I attended a several-day seminar with a rather unusual title: "Danger: Art at Work — Worship and the Arts." As a church musician, I was intrigued and engaged by the idea that art in its various forms could not only soothe and comfort, but could challenge, question, and raise doubts about one's beliefs.

One workshop asked, What do you do with a difficult, hard-to-understand Bible story, or for that matter any challenging life story? The answer: You make art out of it (of course!) as a way of wrestling with it, lamenting it, trying to process it, or making sense out of it. The danger? It might provoke alternate responses and re-form your cherished convictions, although ultimately they may be more real and life-giving and less authoritarian than doctrines that have been handed down to you.

Bill Henderson's "The Family Bible" is a collection of some 66 poems centering on his struggle with the fundamentalist, literalist religion of his childhood and youth, with its contradictions of a loving and angry God and stories of kindness and violence. The poems are very candid and frank, with plain, direct language, exposing the raw edges of life. Wherever you are on the spectrum of spirituality or religion, these poems could be hazardous to some long-held, cherished traditions and beliefs. But there are also momentary glimpses of his maintaining his faith in spite of the struggles — or maybe through them.

A big clue as to where he is coming from is the first poem, one of the shortest, which I think is a gem.

"Faith"

I wanted to be

An atheist

But I lost

My faith.

Another poem that stands out for me is "Liam," in which Mr. Henderson's doubt is answered in a movingly touching moment with an epileptic 7-year-old.

At church, my turn to read

The lesson from my beat up Bible,

(Presented to "Billy," Oak Park

Sunday School, Philadelphia, 1949).

I recite that David defeats

The Moabites, executes two out of

Three prisoners face down in dirt

And praises the God we worship.

Afterwards I float from the bleeding

Altar, wondering what I am doing

Back here among the bloody Christians

Of my childhood.

A seven year old spirit,

Little suffering Liam the epileptic,

Appears from the pews.

A football helmet on his head,

His protection from daily seizures.

Liam hugs my knees hard.

Wordless.

I toss the Bible in a pew.

Now I know what I am doing

Back here.

The same qualities are in "Park Avenue," as it captures both the somber, unvarnished reality of his cancer diagnosis and a glimmer of revelation.

"Cancer" the oncologist

Quietly announces.

Surgery, chemo, radiation etc.

"A fighting chance."

Wandering out of her office

Down Park Avenue,

I come to an immense church,

Stumble up the steps into

A rapture of marble,

Stained glass,

Looming organ,

Velvet cushioned pews,

Immortal slabs of thanks

For wealthy dead donors.

I duck under the pew,

Shut my eyes,

Block it out,

I find Him whom

I am seeking.

Recurring figures in the poems include his dogmatic Pop, who didn't say much but whose words stayed with him, and a religious broadcaster, the Rev. Carl McIntire, heard regularly on Pop's radio. Several poems grapple with the poignant story of his Jewish-Catholic sister-in-law, Debby, having cancer and brain surgery, and then being in a vegetative state for 22 years.

Mr. Henderson's biographical notes say that he "is an elder and occasional lay preacher at his local Long Island church" and is a "close reader of the Bible." It is clear that he knows the Bible and Christian history well, and it shows in a number of poems that prod and poke with blasphemy and irreverence: "Questions for God," "Questions for Christians," "Questions for the Devil," for St. Augustine, for Martin Luther. There are doses of lighter moments and humor, as well, with bits about children's playfulness, his sexual awakening, evangelists' teeth, and Howdy Doody.

The book could have been warmed up a bit by a more interesting layout or typography, or some graphics or artwork; although maybe the visual starkness of it is intended to reflect the bare realities that Mr. Henderson portrays.

"The Family Bible" is a short volume; it could be an easy and fast read, but it is not always easy to digest. It seems to me to be a personal and thoughtful elaboration from his life experiences on what he has written in a memoir, "Cathedral: An Illness and a Healing": ". . . atheists imagine that faith is too easy and believers too simple . . . sometimes faith evaporates . . . but for many of us, it returns. Besides . . . I don't know enough about God to be an atheist."

The poems have an unadorned truthfulness to them as well as hints of revelation that come from Mr. Henderson's own kind of spirituality, and that makes me want to come back to them. The very last poem is a wonderful companion to the first, and the two form bookends of sorts to the collection. The title and whole poem total seven words. I won't give it away, but it, too, is a treasure.

Thomas Bohlert writes about music and books for The Star. He lives in Springs. Director of music at the East Hampton Presbyterian Church from 2000 to 2016, he is now organist for the Hamptons Lutheran Parish.

Bill Henderson is the founder and editor of Pushcart Press. He lives in Springs and Maine.