It almost looked like a dinner plate, Tim Miller said this week.

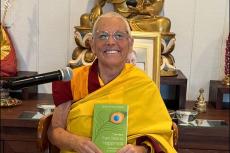

Mr. Miller recalled the object his niece, Adelynn O’Shea, who just started fifth grade at the Springs School, pulled from the water near Three Mile Harbor on Aug. 26.

Adelynn, Mr. Miller, and their families were boating. “We were on my father-in-law’s boat,” Mr. Miller said. “We swam ashore and were walking around by one of the estuaries — I’m not going to tell you exactly which one — and my niece came up to me with this thing.”

“Was it an oyster?” they wondered. “Sure enough, it was,” Mr. Miller said. “It was the biggest I’ve ever seen.” They took it to the boat, said Mr. Miller, who holds an East Hampton Town shellfish permit, and measured it. The oyster was 8.25 inches long, 5.5 inches wide, and 2.25 inches thick. It weighed 1.66 pounds. “It was just mind-blowing because of how big it was.”

Oysters of this size are “pretty few and far between,” said John (Barley) Dunne, director of the town’s shellfish hatchery. “They’re out there, but we don’t see too many of them unless you spend a lot of time in the water.”

Based on pictures forwarded by Mr. Miller, Mr. Dunne said the specimen was most likely seeded by the hatchery, “because it looked like it wasn’t attached to anything else.” It is not difficult to distinguish between “wild” and hatchery-raised oysters, he said. “The wild ones will show some point of attachment at the hinge,” such as to a bulkhead or a rock, “whereas hatchery oysters have no imprint by the hinge.”

Larval oysters are attracted to the shells of other oysters and clams, but in the wild any hard and solid surface can serve as an attachment point, allowing oysters to form large reefs. A single oyster setting on the bottom indicates that it was seeded, Mr. Dunne said.

The oyster that Adelynn found is probably 10 to 15 years old, he said.

“We felt bad taking such an old oyster,” Mr. Miller said. The day after it was found, “we ended up putting it back where it was.”

“They put it back, that’s good,” Mr. Dunne said. “It will keep doing its thing,” meaning spawning and filtering. Filter-feeding bivalves that consume algae and other particles, an adult oyster can filter an estimated 25 to 50 gallons of water per day, depending on environmental conditions.

“Usually,” Mr. Dunne said, “they get picked up before they reach that size, but they’re out there. I do some surveying around our seeding grounds and see them occasionally. But that one,” he said of the oyster Adelynn found last week, “is definitely one of the biggest.”