Leonard Ackerman moved to East Hampton Village in 1972 with his wife, Judith, and their two young daughters. He worked as a real estate lawyer out of a back office in a brokerage, drafting contracts.

It used to be a joke,” he said in a recent phone call. “Once people put in an offer, if you let them get past the Shinnecock Canal without signing a contract, you’d never complete the deal.”

Humble beginnings.

But fast-forward 45 years. It’s 2017, and Mr. Ackerman is in his late 70s. He has had a long, successful career as a “country lawyer” and developer. He lives on Georgica Pond.

That same year, Judie, his wife of 55 years, died.

In grief, he began corresponding with another recent widower, Carl Butz, publisher of The Mountain Messenger, a weekly newspaper in California

Mr. Butz invited him to begin a weekly column. He hasn’t missed a single deadline since, writing under the pen name Lenny Ackerman. Around the same time, he started painting watercolors, taking lessons at the Armory Art Center in West Palm Beach, Fla.

And he began to churn out books.

His fourth, “Leibisch’s Journey,” about his father’s emigration at age 12 from Ukraine and his childhood, is the subject of a Tuesday event at the Hedges Inn, where Mr. Ackerman will be interviewed by Carolyn Brody, who recently sold BookHampton after a decade of ownership.

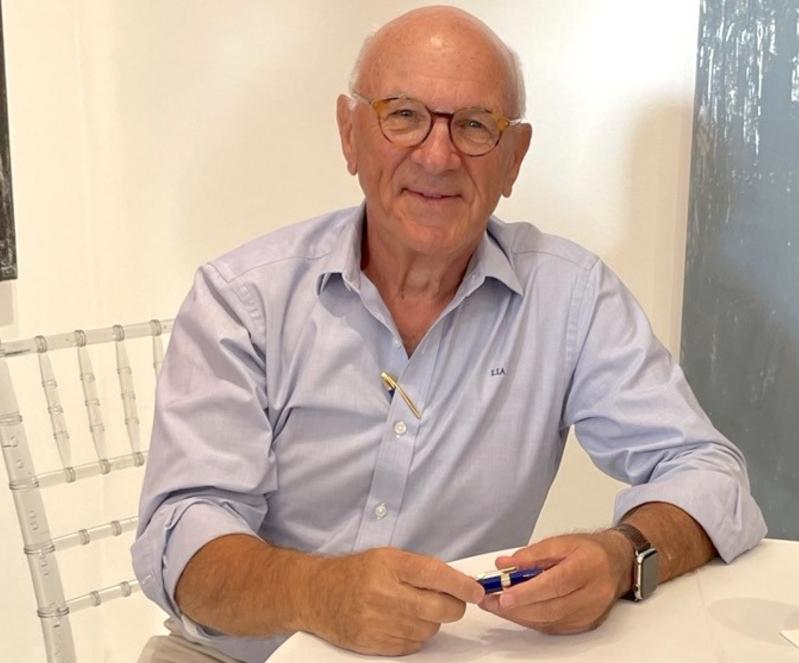

The pace at which Mr. Ackerman moves belies his 86 years.

Fashionably dressed, he’s often seen driving through the village in his 1960 Morgan convertible. He has a calm, friendly manner, but also comes across as thoughtful and strategic, and sometimes speaks sotto voce. He gathers secrets in confidence.

In his newspaper column last week, he was quoting Thoreau and talking about an overnight camping trip in the Maine woods. He’s not your grandfather’s grandfather.

As he’s slowly taken to the role of artist and author, he has continued to be a principal at his village law firm Ackerman, Pachman, Brown, Goldstein & Margolin. (He credits Alison Stone, his personal assistant and editor, with helping shape both his columns and his books.)

In June, during the 25th anniversary of a lawyers lunch he started after 9/11 to foster community among East End attorneys, one attendee described Mr. Ackerman as a sort of “Godfather” figure, minus the violence. Everyone, at some point in their careers, goes to Lenny for advice. He delegates work and helps solve problems. Lawyers from every local office are invited; 65 attended this year.

His new book was born, oddly, after he heard his father speaking fluent Spanish in Miami, only a year before he died in 1990. Until that time, he had never heard his father speak any language other than Yiddish, Russian, or English. It was a shock and a mystery. For years, Mr. Ackerman wondered about it.

“He never spoke Spanish. And yet, it was there. It was always there.”

With the start of the war in Ukraine and the re-election of President Trump and his tough border talk and supercharged deportation policies, Mr. Ackerman thought more about his immigrant father and his journey.

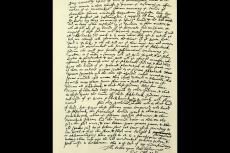

Those two things, together with an ancient Hermés briefcase he carried for decades, and in which he stashed his father’s passport and personal papers, coalesced into the book idea.

Modern parents might struggle to imagine what Mr. Ackerman’s grandparents faced when they told his father, then only 12, to flee their Ukrainian village during the upheaval of the Russian Revolution, amidst pogroms and rampant antisemitism.

The plan was for young Leibisch to take, in Mr. Ackerman’s words, the “battle-scarred, patchwork railway system” west to Hamburg to board a ship bound for the United States, where he would meet up with his older brother Sydney, who had already emigrated.

However, he was diverted to Argentina, where he was forced to build a new life alone, before finally arriving in America a full five years behind schedule. Along the way, he picked up Spanish, endured hardships, and learned lessons that shaped his complex personality, leaving him “forever haunted by the past and the fate of the family he left behind.”

The book blends scenes from Leibisch’s early life with fictional characters and historical research so that it reads like a mixture of a biography and historical fiction.

Leibisch Ackerman grew into a tough man who ran a parking garage in Rochester, and was perhaps not the warmest father. Lenny said he could count on one hand the times they spent together in recreation, and that’s counting picking off pigeons with a BB gun at his father’s garage.

“For me, writing this book was learning about him,” said Mr. Ackerman, “and wanting to relate that to my children and my grandchildren, to my brother’s children and to my sister’s child. I wanted them to know more about where they came from, to appreciate their roots.”

“My father wasn’t one to compliment. Would he be proud of this? Yeah, I think he would be. And I think he’d probably fill in a lot of the blanks. He’d tell me, you know, you didn’t get this right. I didn’t do this.”