The idea of an orchard was “always in the back of my mind,” Robert Hefner said as he walked through the collection of dwarf and semi-dwarf fruit trees growing on his Town Lane property in Amagansett on an early October afternoon.

Growing up, his family had two acres of a much larger orchard in Shelburne, Mass. “The garage in the fall would be full of stacks of apples,” he said. “They were all McIntosh. And we had two Northern Spy trees, but McIntosh was what we sold, and the whole family would sort them — my mother, sister, me, and my father, after work. And then on Fridays and Saturdays my father and I would put them in the back of the Dodge station wagon and drive down to Northampton and sell them at farm stands.”

“As I recall it was 90 cents a bushel, so that’s 40 pounds of apples for 90 cents,” he said. “They were good apples, so they were successful.” He continued to pick the apples during visits to see his mother until the early 1990s, later with his wife, the late Isabel (Min) Spear Hefner. They bought the land on Town Lane in 1995, built their house the following year, and planted the first four apple trees, bought from an orchard in Bridgehampton, around the year 2000.

“Those big trees,” he said, pointing them out. “The Mutsu, two Goldrush, and the Winesap.” He had printed out a list of all 16 varieties now growing on the property, along with a brief historical context for each. Mr. Hefner is a historic preservationist and the former director of historic services for East Hampton Village, so context matters to him.

The Goldrush trees were the only ones still filled with fruit in early October. (“Developed at Purdue University to be scab-resistant,” the listing read. “Has a complex pedigree that includes Golden Delicious, with scab resistance coming from a Siberian crabapple. Released to nurseries in 1994.”)

“We got more from different places as we went along. Being a historian, and liking research and books, that’s when I really started learning more about the varieties and what would be fun.” He found a Cox’s Orange Pippin tree (“raised from a seed [pip] by Richard Cox about 1825”), which he called his favorite apple, in the orchard in Bridgehampton, and planted a Grimes Golden (“originated in West Virginia, first record of the apple is its sale to New Orleans traders in 1804. A parent of Golden Delicious”) after learning it was someone else’s favorite.

More recently he acquired a Newtown Pippin (“one of the oldest American varieties, raised from a seedling in Newtown, Long Island. Grown by Washington and Jefferson”) from a nursery in California called Trees of Antiquity. “A very famous apple,” he said. “I felt I should have that.” It was rated among the highest by S.A. Beach, the author of “The Apples of New York,” a two-volume guide published in 1905 containing detailed descriptions and ratings of “hundreds and hundreds” of apple varieties.

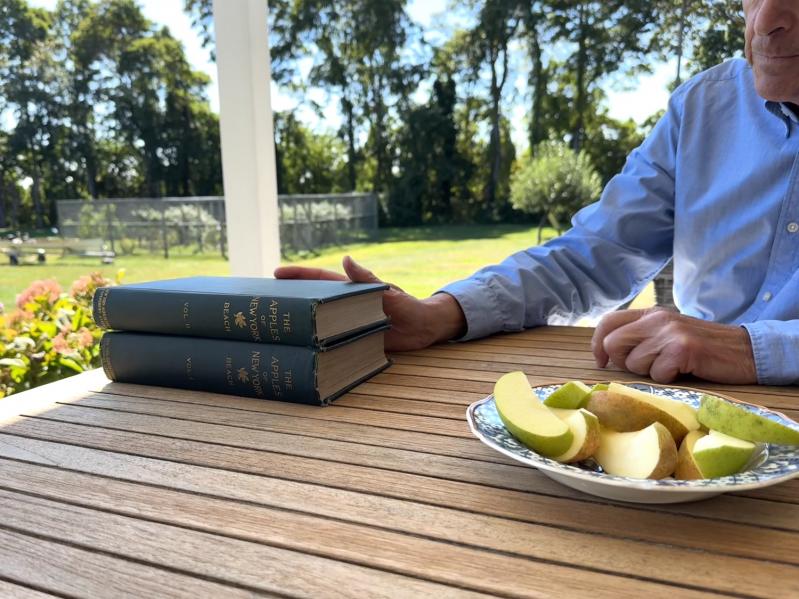

He walked into the house and returned with his set of Mr. Beach’s works, setting the volumes on the table on his back porch. “This is a bible of the historic apples,” he said. “But, you know, even to this day there are apple varieties that are unnamed. There was a stand up near Concord, Mass., a little orchard the guy had, and he had something called ‘rusty yellows’ — they were like a Golden Delicious but they were more russeted, and they tasted a little bit different,” he said. “They were always there in his orchard, but he didn’t know what they were.” Mr. Hefner had looked through records for a mention of a special apple from that area, to no avail.

Apple history is surprisingly easy to track, at least in the cases of the named varieties. The seeds are “unpredictable,” he explained, as planting a seed from a specific apple will not necessarily produce a tree of the same variety. And so throughout history, when a tree would produce a “particularly incredible apple” that gained a reputation on somebody’s farm, it would be named, generally after the tree’s owner, and entered into some sort of horticultural exhibition. Pieces of that original tree would then be grafted to rootstocks to propagate the fruit.

“And then it goes on and on,” he said. He flipped through one of the volumes to a page featuring a photograph taken in 1896 of the original McIntosh tree — the source of the apples he and his family had sold in Massachusetts. A man identified as Allan McIntosh, the “son of the discoverer,” is pictured beside it, looking up at its bare branches.

Most of the Cox’s Orange Pippins had fallen by mid-September, and the Grimes Goldens followed. The last apples of the season are the Goldrushes, which Mr. Hefner said he does not pick until Thanksgiving, or even early December. “They keep really well, and the taste actually develops in the refrigerator,” he said.

There were still a few berries left in the fenced-in enclosure behind the main concentration of trees — a few raspberries and one tiny strawberry. A Meyer lemon tree is all that will grow during January and February, but his final apples will last until February or March in the refrigerator, and then he will have his berry preserves. Spring is the busiest time, when he does most of the pruning and thinning, and the apple blossoms will start to appear in late April. The berries will return in July, the peaches peak in August, and then the apples will be ripe again, too.

“This is not at all related to a real orchard — this is a hobby. The only interesting thing about this orchard is all the different varieties, which I suppose, because I’m a historian, I suppose that has something to do with it,” he said. “It’s a calendar of what you’re doing, and you always have something to do. So that’s good.”