Marie-Christophe de Menil, a child of a fabulously wealthy, cosmopolitan, and culturally prominent family, died on Aug. 5 at her apartment in Manhattan at the age of 92. Her brother George said her death followed a long siege of arthritis, which left her bedridden toward the end.

Ms. de Menil, an openhanded patron and close friend of many key artists of the past century, Willem de Kooning prominent among them, was never one to hide her light under a bushel, not if she could help it anyway. Unlike her quieter sister Adelaide, who has been well known and much admired here as a champion of South Fork baymen and preserver of the area’s historic houses, Christophe, from an early age, often flouted society’s expectations. The gown she chose for her debut in 1952, for example, weighed nearly 15 pounds; photos of it show her entirely encased in what looks like a four-leaf clover, and it seems impossible that the wearer could move a step. Underneath, though, she was wearing culottes, and danced the night away.

Born in Paris in 1933, she was the eldest of five children, all of whom, like their parents, have differed from the workaday run of billionaires in how they spend their money — not on jewels or yachts, but on causes. In her case, the cause was art. She supported artists, both contemporary and avant-garde, and creative people of every stripe — painters, filmmakers, poets, writers, designers, dancers, musicians — with commissions, purchases, and donations to museums, and often included them in the many parties she gave both here and in the city.

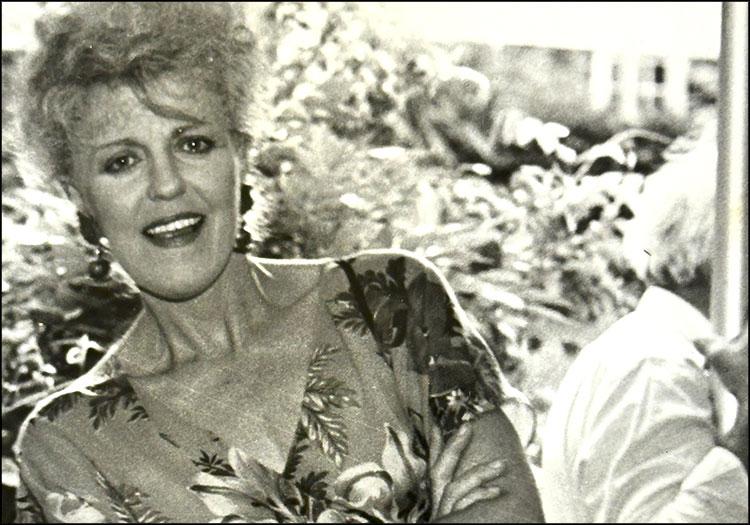

A tall and handsome woman who carried herself with a regal air, Ms. de Menil was a grande dame of high Manhattan society, though she was never content to leave it at that. Along with her wealth and social standing, she eventually got what she really wanted, a career of her own, as a fashion and jewelry designer. In 1981, her friend Robert Wilson, founder of the Watermill Center laboratory for the arts (he died just five days before she did), hired her to design costumes for his experimental theater pieces, and later on, while living in an Upper East Side carriage house, she established herself as a respected couturier. One of her ball gowns is in the Metropolitan Museum’s Costume Institute.

After finding the occupation that gave her a new purpose in life, she told The New York Times, “I did things for others. Now I’m doing something for myself. Flowering, in a way. Expanding. Now I have a vocation and much better bearings.”

The parents of the five de Menil siblings, Dominique Schlumberger and John de Menil, met at a dance in the Palace of Versailles and were married in 1931. For the marriage, Dominique, who’d been brought up Protestant, converted to John’s Catholicism. Their first three children were born in France, the next two in the United States.

John’s family was titled but not rich; Dominique’s had accumulated a fortune in textiles in the 19th century that her father, a physicist, enlarged enormously by inventing and patenting, in 1934, an electric measuring device that made it possible to determine the location of an oil deposit. The process, called “well-logging,” was adopted by oil companies around the world and remains in use, with Schlumberger Ltd. still the global leader.

In 1940, as the Nazis were invading France, Dominique fled Paris for Marseille, where both Christophe and her younger sister Adelaide came down with chickenpox. Dominique swathed the little girls in loden coats to hide their spots, and somehow managed, with the infant Georges in her arms, to get past the German authorities to Spain. John, who was working by then as an executive for Schlumberger, met them in Havana, whence they traveled on to the firm’s U.S. headquarters in Houston, Texas. Ever since, Houston has been the de Menils’ principal home among several, including a castle in France, and is home today to the famous Menil Collection of paintings, sculptures, prints, drawings, photographs, rare books and more. Reportedly, the disparate collections of the de Menil siblings will wind up there as well.

Through the years, while based primarily in Manhattan, Christophe de Menil owned houses on the South Fork including for many years on Indian Wells Highway in Amagansett. As far as can be determined, her last house here was in Northwest, at Barcelona Point.

She was married twice. In 1959, at the age of 26, she married Robert Thurman, who was 18 and about to enter Harvard. He dropped out before his junior year and headed to India to “find himself,” leaving his wife and baby daughter, Taya, behind. The marriage ended in divorce; he became a well-known Buddhist scholar and monk.

Her daughter, Taya, grew up riding horses in the summers at the Topping Riding Club in Sagaponack, and participated as a teenager in what has since become the Hampton Classic, then being held in a field at Dune Alpin Farm in East Hampton. Except among horse people, the show was little known, not even a shadow of the social spectacle it is today, and it looked to be on its last legs when Ms. de Menil stepped in and saved it.

“She was the driving force behind resurrecting the show in 1976,” said Shanette Barth Cohen, the Classic’s executive director. Many years later, the show established an annual award called the Firefly, and Ms. de Menil was of one of the first to receive it.

Her second husband was Enrique Castro-Cid, a Chilean artist. They wed in 1971 and divorced in 1974. They had no children, and she never remarried.

All four of Ms. de Menil’s siblings survive her. In addition to her brother Georges, she leaves another brother, Francois, and two sisters, Adelaide de Menil Carpenter and Fariha al-Jerrahi, born Phillipa de Menil, who since 1995 has been the spiritual guide and Sheikha of a Sufi community in New York City. Francois and Adelaide, like Christophe, owned large houses here for many years.

Ms. de Menil is also survived by her daughter, Taya Thurman; two grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren. Another grandchild, Dash Snow, a promising artist whom she much loved, died in 2009 at the age of 27 of a drug overdose.