During the Second World War, East Hampton boys in the services communicated with one another across the far-flung fields of battle using a method that is astonishing today and yet worked remarkably well: They wrote letters home to the editor of The Star; the Star collated and printed snippets of their news in a column titled “Army, Navy, and Marines” that ran each week on Page Four, and then the service members read all about one another’s escapades and heroics a couple weeks later when their copy of the newspaper reached them on battleships and battlefields, in training barracks and hospitals, from Iwo Jima to Oklahoma to Anzio.

Sometimes the letters from these young men and women (serving as WACs or nurses) arrived home in East Hampton via Victory Mail, the system in which the military photographed letters onto microfilm, flew the film overseas, then printed the letters back onto paper at their destination. Sometimes it arrived on novelty postcards or air-mail onionskin. The goal was for every Bonac boy and girl serving in wartime to get a copy of the newspaper, regardless of where they were stationed.

The Star ran notices regularly, seeking assistance: “HELP SEND THE STAR. Each week over 750 copies of The Star are sent to 42 States and to most of the foreign stations to the men and women of East Hampton who are serving in the Army, Navy, Coast Guard, or U. S. Marines. Some have their own subscriptions. Other copies are mailed without charge. The Star is grateful for contributions to help defray this cost.”

“The Stars arrive in bunches, whenever we get in port,” one sailor wrote. “I take a day and read them all, even the want ads.”

From the summer after Pearl Harbor up through late June of 1946 (two weeks after the Allied Victory Parade in London), any given issue contained updates from two dozen or more service members — jokes, salutations, and occasionally poetic dispatches from these youth at war. Here is a typical note, among many others that made print on the random Thursday of Sept. 10, 1942:

"From up in the Far North country, Pvt. Ernest S. Carde writes that the pictures of the boys in service (how about the pictures of the girls in service?) gave him quite a kick. "A June paper just come in with ‘Moose’ Fithian’s picture in it,” Private Carde writes. “I’d like to say ‘hello’ to Moose through The Star and wish him best of luck.” The Star editor, who had served in France in 1917 and 1918, commented with the jaunty jocularity of a soldier growing old: That’s a mighty long “Moose Call” from the frozen north, via Bonac to Kangarooland.

Many of the dispatches were matter-of-fact notes of injury, furlough, transfer, or discharge: “Sgt. James Walker of Wainscott, who received burns during the invasion of North Africa, has received a medical discharge.” Or, “Legion of Merit for Colonel Frank D. Weir, of the Marine Corps, for service on the staff of the commander of amphibious forces, South Pacific, from initial landings on Guadalcanal to the New Georgia campaign in July 1943.”

Lt. John Marshall “arrived in Africa with French and Italian grammar books stuffed in his pockets.” David Gilmartin, a machinist’s mate in the Navy and survivor of Pearl Harbor, had “since Pearl Harbor put in at Casablanca, Rio de Janeiro, Bombay, ports in Australia, and San Francisco.” Pvt. Joe DiSunno wrote to say he had received two stars within the one month since he landed in France as a radio operator. Alfred J. “Brownie” Bennett was promoted to gun captain on a destroyer in the Pacific, having “participated in two major island invasions.” Brownie said they had “damaged plenty” of Japanese ships “and although the Emperor’s fighters used to come to America for iron and steel they have now discovered a great dislike to the same products when delivered to their door.”

Carl Geyer, a Seabee and Sergeant First Class with the Pacific fleet, sent a bright postcard from the South Pacific showing Captain Bligh’s ship The Bounty. (Commentary from the editorial peanut gallery: “That Capt. Bligh would have been a tough baby to cook for, Carl.”) Eugene Beckwith, Machinist’s Mate Second Class, wrote nearly 600 words describing his experiences landing six times on Normandy Beach on D-Day, unloading tanks for the invading army.

“The sixth time we were the only ship going in and the Jerries really had our range,” he reported. “They formed a ring of shells around us but got no direct hits. These guys must be blind.” Like many of his fellow servicemen, Beckwith signed off by waving away parental concern back home: “There is nothing to worry about so please don’t.”

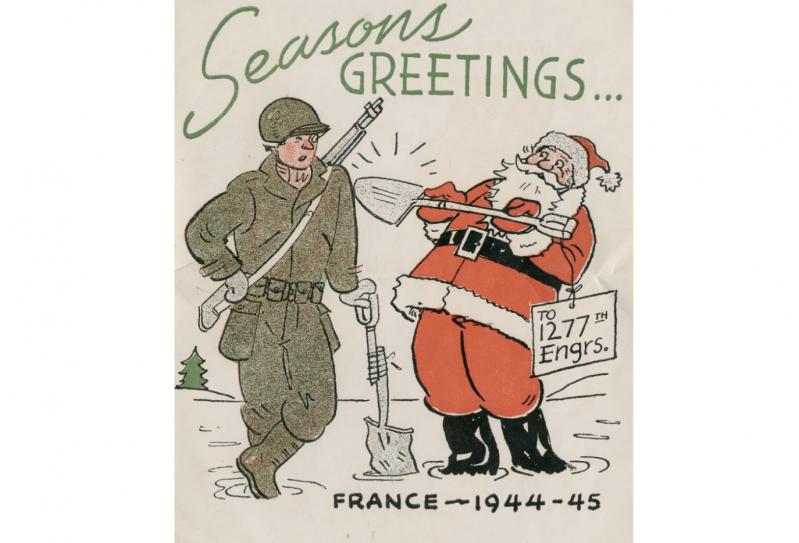

Between Thanksgiving and Christmas, the volume of this group correspondence would increase considerably. “Greetings to the Folks Back Home from the boys in all branches of the service have been piling up this week and just for a starter we’ll go through the mail stacked on the left side of the desk and sort the holiday greetings to one side,” reported the editor on Thursday, Dec. 21, 1944, midway through the Battle of the Bulge.

Sgt. Howard Morris, with the Air Force in northeastern India, was among the dozen or so Bonackers who sent a Christmas card that week; his showed a cartoon G.I. surrounded by a harem of beguiling women. “I can imagine what a perfect Christmas will be spent in East Hampton,” Morris wrote, wistfully. “Next year I’m hoping that it will be different. Oh, well. I’ll think of you all while I eat my dinner this year in Assam.”

Sometimes the soldiers complained about the efficacy of this newsprint telegraph. Wrote Sgt. Morris in India, "Have you been sending my Star to me? I haven’t had a copy since I came to India and am very homesick for one.” You can hear near-desperation in the repeated and mounting pleading from the editor, in reply, that the men needed to send their new addresses when they were transferred to a new station: “ALL WE NEED is the address and the Stars go out of East Hampton with a fair chance of reaching men in service. But if we don’t have the addresses we NO CAN DO.”

It wasn’t all mess-hall jokes and innuendos about pretty Parisian girls, of course. Too frequently the boys learned from the latest Star of the death of an old classmate: “Since the news was received last week that Chief Machinist’s Mate Andrew ‘Junie’ Gilbride was missing after the sinking of the cruiser Juneau in the Solomon Islands area, we have heard many expressions of regret.” The Juneau was sunk by Japanese torpedoes during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal on November 13, 1942; according to the Long Island Collection at the East Hampton Library, 43 Bonackers died in service during the war. Junie was from Sag Harbor.

Some of the soldiers wrote home with poignancy. “I’m afraid that I wasn’t born under a lucky star as I can’t seem to run into anyone from home,” wrote Boatswain’s Mate First Class Bob Flynn. “I read in The Star where all of the boys are running into other boys they know; maybe some day I will be lucky. It was just about a year ago that I was home — it seems like ages ago. If we are lucky we should be back in time for the summer — that is, if we are lucky. I imagine the old town must be dead right now. I remember how surprised I was when I was home, for there wasn’t a soul around. After seeing hot weather continually for the last year it would be a pleasure to see snow again.”

And not infrequently the awe at their great and terrible purpose rings through. Lieutenant Charles Osborne, with the Air Force, wrote at length from Italy in 1944. “I’d like to be able to tell you some of the things I have seen since I started flying Liberators in combat but I can’t. I’ve seen the cities of Vienna, Budapest, Bucharest, and Belgrade from altitudes, plus several other minor places, but that’s about all that can be said.”