THIS IS a story about food. It starts on a boat with one man and a fishing pole. It ends at one of East Hampton’s best restaurants. It could be a very long story spanning several states, at least two continents, and dozens of pairs of hands along the way. But it’s not, and that’s what makes it worth telling.

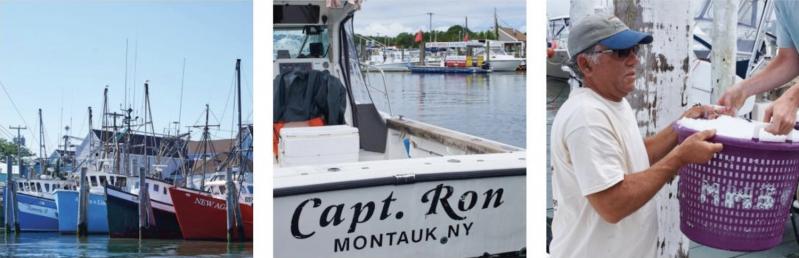

It’s just after noon on a sultry day in early July when Capt. Ron Onorato steers his 29-foot sport-fishing boat through the Montauk Harbor inlet and into the open waters of Block Island Sound, bound for a spot two miles off the Point where he expects to find a jackpot of black sea bass.

Onorato is one of only a dozen or so commercial rod-and-reel fishermen operating out of Montauk Harbor. “To me, catching a fish on a hook is more exciting than dragging a net,” he says. He also runs a charter business, Capt. Ron’s Fishing, and had been out in the morning with paying customers searching for the same bounty.

“Today, to be able to make a living, you’ve got to do both.”

In 6 or so feet of water, with the Montauk Lighthouse in the near distance, the fish finder lights up.

“There!” He points out the right sized blips that tell him he’s found his mark, grabs a pole from the cabin, pops on a lure, and drops his line in the water just off the boat. Not 30 seconds later, he’s reeling in two black sea bass. He drops his line again. Bam! Two more in less than a minute, and again, and again.

At this rate, he’ll catch his 50-pound daily quota in an hour. But fish can be fickle, and after he makes it look all too easy half a dozen times, they seem determined to make him work for those last few pounds.

Undaunted, he refers to what he calls his “Book of Numbers,” a well-worn, meticulously kept record of sweet-spot coordinates that he says will be buried along with him when he dies. Then he steers a course for more fruitful waters, snagging a few more sea bass before turning his attention to porgy, a.k.a. Montauk sea bream, which has a daily quota of 800 pounds.

When he’s ready to call it a day, he texts Joseph Realmuto, the executive chef of the Honest Man Restaurant Group, whose South Fork eateries include Nick and Toni’s and Rowdy Hall, to see if he wants to claim the catch. The answer: an emphatic “Yes.” He’ll take it all, sight unseen, and it will be among the freshest fish on any restaurant table that week.

On the way back to port, the captain takes a detour to catch a pair of big bluefish. With two, he says, “Joe will have enough to put it on the menu.”

At the docks, he packs his fish out and weighs it at a dealer’s warehouse, where it’s iced down and set aside for Nick and Toni’s. Forty-nine pounds of sea bass, 16 of bluefish, and 6 of porgy.

Black sea bass “pay between $6 and $7 a pound to the boat,” he says, but every sale is a negotiation with the dealer, who buys the fish off the boat and sells it on-ward. For Ron’s catch, which has a ready buyer willing to pay a premium, the price to both fisherman and dealer will likely be on the higher side.

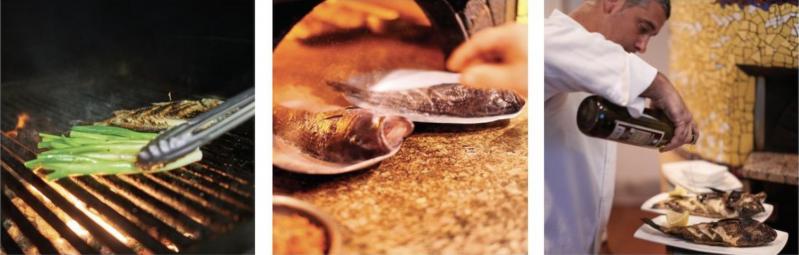

“I don’t mind paying more knowing that I’m going to get that quality,” Realmuto, the chef, says the next day, after preparing a sample of the dishes he would serve at the restaurant that night. He was at the dock at 8 a.m. to get the fish, then back in the Nick and Toni’s kitchen with his chef de cuisine, Bryan Futerman, a leader in the local Slow Food movement, by mid-morning.

The sea bass would be the whole fish of the day, wood-oven roasted. “Some we’ll fillet, and we’ll do an amuse bouche of smoked-bluefish paté,” Realmuto says.

Along with a description of the specials, waitstaff will tell patrons that it was “pole-caught” just yesterday by Captain Onorato. “When you mention it to customers — what the fishermen caught, when they caught it, the steps used to catch it — they are very intrigued.”

At Nick and Toni’s “people tonight will be eating 28-hour old fish.”

On the South Fork, ordering fish that fresh is harder than you might imagine. “It’s coming into Montauk, but some goes to the Fulton Fish Market (in the Bronx. You’ve already lost two days there. It’s sent back by truck,” Realmuto says. “It could be another two days before we get a fish that was brought in 20 minutes from me.” And, of course, popular fish caught abroad or in other states will have an even more circuitous route from sea to plate.

As natural as relationships like the one Realmuto has forged with Captain Onorato might seem in a seaside community — especially in an age when the farm-to-table movement has fostered a growing appreciation for the origin of so many ingredients on a restaurant’s menu — they remain uncommon these days.

A state-licensed commercial fisherman can still peddle his catch directly to a final consumer, but that triggers a whole new set of reporting requirements mimicking those for a dealer, who has to report a range of landing data including the true weight of the species caught based on certified scales that are legal for trade. That information is ultimately used by the federal government to “determine the total catch for a given year” and to manage the fisheries, explained Victor Vecchio, a fishery reporting specialist with the National Marine Fisheries Service.

Realmuto met Onorato through the Dock to Dish restaurant supported fisheries program, which is based on some of the same principals as community-supported agriculture. “It’s like ‘know your farmer,’ but it’s ‘know your fisherman,’ ” said Sean Barrett, its founder. “It’s restoring the identity of the commercial fisherman.”

Dock to Dish began as a direct-to-consumer program, then branched out to include restaurants. Members paid a set fee for a share of a fisherman's premium catch but also took a certain poundage of their bycatch, the less desirable, cheaper fish like porgy or bluefish. The Dock to Dish mission, at its most basic level, was to connect consumers more directly with small-scale commercial fishermen who practice sustainable catch methods.

Its broader aims, as outlined on its website, were revolutionary concepts in the face of global seafood market realities: “to engage our fishermen and community members in a more transparent local food market with a minimized chain of custody” and “to fundamentally change seafood marketplaces by demonstrating to producers, through consumer demand, the economic and ecological value of traceable, sustainable seafood.”

“I was on board from day one,” Realmuto said. What appealed to him “first and foremost is the sustainability, and how it’s protecting our resources,” but he also liked that he was supporting local fisher men in the process. “By paying them a higher landing rate for their fish . . . as opposed to going through all the middlemen, it allows them to catch their limit and get paid for bycatch.”

Without the program, bycatch is often simply thrown back in the water. “It forces the chef to use a product we’ve never really used before,” Realmuto said, and that’s an education for the customers, too, showing them that porgy and sea robin, say, can be “as good as tuna or striped bass.”

“Traditionally, before the whole sea-to-table movement, fishermen would simply pack their fish out and sell it to a dealer somewhere,” explained Vecchio, who has an office in East Hampton and is in charge of all of New York State. “Occasionally, fishermen could sell their fish at the dock if you were fortunate enough to be there at the dock when they were unloading.”

Once it’s at the Fulton market, “it can change hands anywhere between one and two dozen times as the brokers and merchants in the market swap and trade,” Barrett said.

“When so many people are handling it, you can see the fillets starting to break apart. A fresher fish, you can see the clarity in the eyes,” Realmuto said.

Another plus: “The fish is really delicious.”

When customers tasted the difference, they were hooked, too.

While Dock to Dish is no longer operating its C.S.F. or R.S.F. out of Montauk, its guiding principles left a deep impression on both restaurateurs and their customers. Chefs like Realmuto, Futerman, and many others on the South Fork and beyond have embraced the idea that buying local should apply to seafood, too.

One point that Dock to Dish worked to drive home for restaurateurs is that “wild, traceable, sustainable U.S. seafood is ultimately the highest priced item on your menu,” Barrett said. By sharing its story, “you create an environment where people are willing to pay higher prices.”

Realmuto may not be able to fill all the seafood slots on his menus with the catch from Captain Ron and small-scale commercial fishermen like him, “but we’re helping local fishermen, educating the staff, educating the client, and doing something we believe in.”