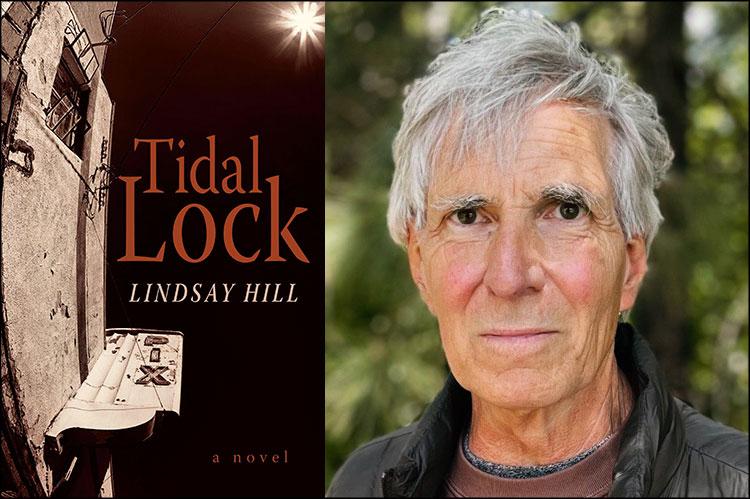

“Tidal Lock”

Lindsay Hill

McPherson & Company, $24

McPherson & Company, an independent small press, recently marked its 50th year of publishing the likes of the modernist Mary Butts, Jaimy Gordon, a National Book Award winner, and Lindsay Hill, a poet and novelist whose first novel, “Sea of Hooks,” was the winner of the 2014 PEN Center USA Fiction Award and received many other honors. His new effort, “Tidal Lock,” is a study of voice that maps the dimensions of psychological reality. It is deserving of an attentive readership.

The city in which the novel takes place has a shifting sense of irreality, populated by abandoned buildings and wreathed in dust. There’s constant demolition, often without notice. Who would give notice, and to whom? The names of buildings, Starry Bright Motel, the Vice Mart, the Pix Theatre (an abandoned theater that still shows films), the Castaways apartments, the Mercury Mirror Works, have a retro/metaphorical feel. A sense of place as psycho-emotional landscape sets in, layers. The city appears to be by the sea, simultaneously suggesting boundary and escape.

“Tidal Lock” proceeds in first-person narration by a young woman who says that her name is sometimes Olana. “Did you ever feel like you didn’t live in a real place? Maybe not. I call this city Tidal Lock. I’m looking for my father or what happened to him.” The captivating sometimes-ness of Olana, together with her compelling and compelled mission, create the drama of the narrative.

What unfolds is nonlinear and carefully structured. Mr. Hill writes his protagonist’s story in a stream of her movements about the city, her observations (look for canny, unusual similes: “I wake engaged like a bike chain wakes when its person starts to peddle”), and most crucially, her memories, which the reader comes to understand as extensive fabrications. The whimsy, the wistfulness, the wickedness. The writing stretches out, exercising, as if seeking corners and edges. The reader is left with a sense of abandonment, longing, trauma. Mr. Hill’s Olana is the essence of an unreliable narrator, and a self-avowed liar to boot, yet the unremitting, layered cascade of her story is unmistakable as metaphorical truth.

The book is crafted, sentence for sentence, as a seemingly impossibly layered mindscape, rich if not overripe in what must be metaphor, must be symbolism. An interrogation of how the density of information, emotion, and psychology is wrought leads to the sense that phrases and clauses have been magnetized together by hitherto unknown polarities. The strangeness is overwhelming, unrelenting, and riveting. There’s a vastness, somehow, to the slim volume.

The novel is put together in a cogent and helpful form — short, titled passages, some only a paragraph, some up to a page or two, are collected into four parts, also titled. And so the book is organized and even, for the careful reader, laced with cross-referencing. Certain of the passages have titles in common, helpful anchors in a complex text. “Trains,” “Fairy Tale,” “The Pix,” “Tourniquets.” The titling of the passages creates solid ground in the quicksand patterning of the novel, a mapping of interconnected outcrops.

With a dense narrative style, Lindsay Hill intertwines strains of the rhetorical “you.” Olana’s direct address to the you that is the reader ranges from the casual, yet keenly stated, “Just so you know — three quarts of blood is half the blood you have,” to the much more stressed, confrontational, and meta: “I can’t fill all these endless empty blanks just to keep you listening.”

With calisthenic illeism and a streak of the confessional, Olana refers to herself as you — extended explanations veer into specific, often traumatic stories and become sculpted outpourings: particular memories, or symbolic renderings of them, or observations on experience. And there is also the you that refers to one, people, those enduring the human condition. The evocation of “you” in its forms and combinations is systemic to the novel, a circulatory system that carries Olana to her reader.

“In case you haven’t already looked it up — tidal lock means not being able to see the other side of something. You can’t see the other side of the moon because the moon is tidally locked with the earth in its orbit for example. Venus and Earth are tidally locked. No one knows why. Things you can’t turn from — things you can’t shake — how the past turns its single face to you — how all you can’t remember lies on its dark side.”

It is not about the difference between truth and lie, or the difference between sane and crazy, or even the difference between real and imagined. It is not those delineations at stake, but instead an understanding of the thick, difficult reality presented. A complex metaphorical fabric persists to the conclusion of the book, yet the author has created narrative progress that should be lauded as revelatory transformation.

How to approach the Gordian knot of the pain of human experience? Not by painstakingly untangling, yet not by cutting through — rather perhaps by apprehending the knot itself as a long song, and singing it to one’s last. Mr. Hill has touched the infinity, and absolute specificity, of living in a trauma-informed reality. The result is complex, mysterious, intriguing, and terribly, terribly touching in the profundity of its wholeness.

Evan Harris is a librarian and writer who lives in East Hampton.

Lindsay Hill, formerly a summertime visitor to Amagansett, lives in Los Angeles.