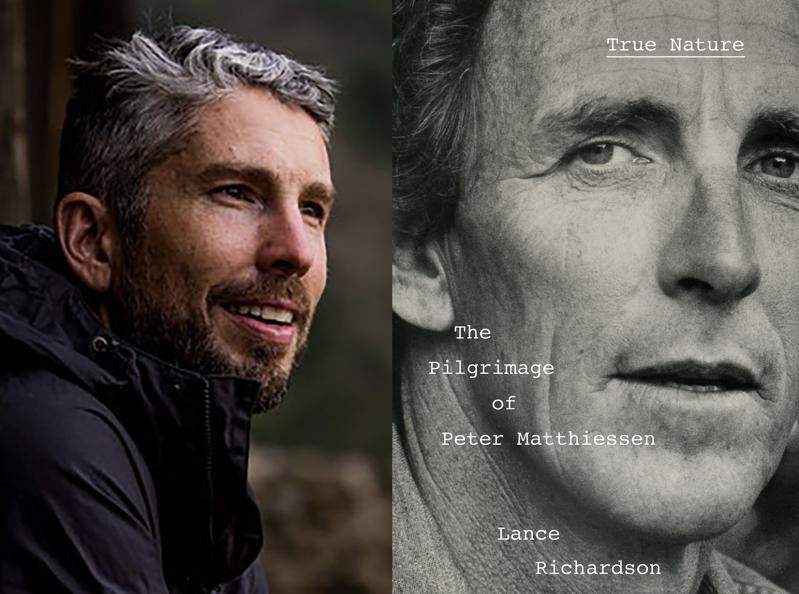

“True Nature”

Lance Richardson

Pantheon, $40

In a foreword to a book titled "The Way of White Clouds: A Buddhist Pilgrimage in Tibet" by A. Govinda, Peter Matthiessen made the distinction between a pilgrimage and an ordinary journey. A pilgrimage "carries its meaning in itself" and operates on "the physical as well as the spiritual plane"; it is a movement "that always starts from an invisible core."

These words serve as the epigraph to an elegant first biography of the author, activist, naturalist, and Zen teacher who made his home in Sagaponack: "True Nature: The Pilgrimage of Peter Matthiessen" by Lance Richardson. Over the course of 600 pages (and 70 pages of notes), the reader will follow the explorer Matthiessen on extended journeys across five continents and seven decades; he was a man seemingly in constant motion. In his novel "At Play in the Fields of the Lord," he wrote of one of his characters, Lewis Moon: "So long as he kept moving he would be all right." I recall a beautiful, favored passage from "The Snow Leopard": "The search may begin with a restless feeling. . . . Yet one senses that there is a source for this deep restlessness; and the path that leads there is not a path to a strange place, but the path home."

Simplicity, ever elusive, and the ongoing search for a lost paradise are central themes that weave throughout Richardson's book. Here is Matthiessen again, in his preface to "Are We There Yet?": "Yet to seek one's own true nature is, as one Zen master has said, 'a way to lead you to your long-lost home.' "

When the writer James Salter was asked again and again by curious people to be introduced to his friend, he wondered "which Peter Matthiessen they would like to meet." Maria Matthiessen, his wife, once said of him: "He is delicious looking, has a sly, quick wit, and just when you are ready to throw in the towel because of his singular self-absorption, he is disarmingly self-deprecating." Elisabeth Sifton, who served as his editor for a number of books, wrote that Matthiessen was "an immensely complicated, neurotic, charming, iron-willed, uncertain, demanding author." And yet, or perhaps because of the multitudes he contained within (in Whitman's phrasing), he wrote 33 books, and became the only author to win the National Book Award for both fiction and nonfiction.

Joan Jiko Halifax, who, like Peter Muryo Matthiessen, was a student of Bernie Tetsugen Glassman, and later also a Zen roshi, said: "Peter also had this sense of irony, a strange sense of humor, or sense of ambivalence, about everything in his life, whether it was Zen or his marriage or whatever. Everything was up for questioning, everything subject to doubt."

When Lance Richardson conceived the idea of writing this biography, three years after Matthiessen's passing, Maria warned him that he was taking on a "vast labyrinth of a subject," something far larger than he might have imagined. Richardson admits in his acknowledgements, "She was right." In my mind this only amplifies the achievement of the book; "True Nature" is beautifully written, generous, but also uncompromising, and Richardson handles the complexities with insight and grace. One of the pleasures for me — one that I hope others may share — is that Richardson's biography is also a book about the craft of writing, from the solitary writer's search for le mot juste, for the appropriate voice or cadence or tone, to the demands, the intricacies, and mechanics of editing, editors, and publishing, the unpredictable reception by readers.

Richardson dedicated eight years to working on "True Nature," and over the course of that time he conducted more than 200 interviews and became a familiar figure at the Ransom Center in Texas — Matthiessen's papers are housed there — where he would explore 227 document boxes and, over an 11-month period, photograph typescripts and journals. Oh, he also traveled to Dai Bosatsu Zendo Kongo-ji in the Catskills for days of sutra chanting and zazen, and, following in the footsteps of Matthiessen's "Snow Leopard" trek, he hiked up to 17,550 feet to visit Shey Gompa, near Crystal Mountain, in the Himalayas of Nepal. "Dedication" hardly seems like the appropriate word.

Richardson writes that "Nature, to Peter Matthiessen, represented a salve for the excesses of civilization." (Matthiessen quotes Crazy Horse in an epigraph to the book by that name: "We do not want your civilization!") Throughout his career, as Richardson notes, Matthiessen was less than fond of the "nature writing" label. "Too narrow . . . and too soft," he offered in a conversation with Gary Snyder. His own work — over the years he wrote about sea birds ("The Wind Birds"), striped bass, cranes ("The Birds of Heaven"), tigers, sharks, and African wildlife — "was intended as a vigorous call to arms." In an illuminating note (I found the notes section of "True Nature" to be a treasure trove), Richardson reveals some jottings made by Matthiessen in preparation for a lecture about his career: "W in A ["Wildlife in America"] . . . 1959. . . . Even then, not a nature writer . . . environmental writer, already concerned with traditional people and social justice."

Which brings us to another flock of books — and Richardson has precise and perceptive commentary on all the writings — from "The Cloud Forest: A Chronicle of the South American Wilderness," 1961, to "The Tree Where Man Was Born: The African Experience," 1972 (with one of the most lyrical prose finales in the language), to "Sal Si Puedes" ("Escape if You Can"), a book that reveals Matthiessen's close connection with Cesar Chavez, 1969, to "Indian Country," 1984, to "In the Spirit of Crazy Horse," 1983, and "Men's Lives," 1986, to name some of the nonfiction titles.

But Matthiessen always saw himself primarily as a novelist. In the words of Richardson, in fact, he was "desperate . . . to be taken seriously as a novelist." So Richardson devotes a long and detailed chapter to "The Watson Years"; rightly so, given that Matthiessen devoted a combined 30 years to the Edgar Watson trilogy and to the condensed one-volume tome that, in 2008, received the National Book Award for fiction. On Peter's face, that night of the awards dinner, "was pure joy." Two years later, "Shadow Country" would also receive an award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters as the "most distinguished American novel" published within the previous five years.

Matthiessen had his detractors and critics over a very long career, and Richardson does not shy away from those controversies. Matthiessen's extraordinary account of the shootout near Wounded Knee in South Dakota in 1975, in which two F.B.I. agents and one Indigenous resident lost their lives — "In the Spirit of Crazy Horse" — following intimidating lawsuits, was withdrawn by the publisher, Viking, and not republished until 1991. Meanwhile, Matthiessen and Viking endured seven years of litigation and depositions before the case was finally cleared. As many readers will know, Leonard Peltier, accused of the crime, served 50 years in prison before President Biden commuted his life sentence in the last hour of his presidency. Matthiessen worked on Peltier's behalf for decades: "You can't do a book like this and then walk away," he said.

"True Nature," the account of a life that spanned the years 1927-2014, rings so true today, right now! Listen to these words of Peter Matthiessen, penned at the turn of this century: "Can we really be so cowed by all the scare talk and false patriotism that we stand by watching our environment despoiled, our civil liberties eroded and our savings stolen, our children's future compromised by arrogant narrow men of totalitarian inclination and stunted vision?"

Nearing the end of my allotted space, I have totally passed over the revealing, sometimes disturbing details of Matthiessen's privileged WASP childhood, of his "charming" parents, Betty and Matty, schooling at St. Bernard's (with his mate, George Plimpton), Hotchkiss, and Yale, his time in Paris as a C.I.A. operative while co-founding The Paris Review, his obsession with Bigfoot and the Yeti, his marriages (three) — "I am no fit mate for anybody," he told Plimpton — his admitted shortcomings, failures really, as a parent (his relationship with Alex is especially moving), the LSD experiments, his time as a bayman, his intrinsic role within the birth of American Zen ("Zen saved him," said his daughter Rue).

Lance Richardson is an accomplished storyteller, so I invite you to enter into this story of a complex, often troubled man in search of simplicity, and to trust Richardson's "lyrical intuitions" and his excellent ear (to echo Matthiessen's own praise of Rachel Carson). At the very end of his life, Matthiessen admitted to an interviewer: "It's been my great aim in life, simplification. Total failure."

I was fortunate to sit beside Muryo roshi in zazen, over years, with my wife, Megan, practicing Zen in the renovated horse stable on Sagaponack's Bridge Lane. Muryo improvised a lovely blessing ceremony for our daughter, "Buddha-baby," he called her, and he also officiated at the wedding of my artist in-laws, Connie Fox (Peter's student for 35 years) and William King, in the Zendo garden, each 78 at the time!

I am at present involved with preserving and extending his legacy, along with Alex Matthiessen and an inspired team. There are the teachings, after all. "The search may begin with a restless feeling. . . . The journey is hard, for the secret place where we have always been is overgrown with thorns and thickets . . . the holy grail is what Zen Buddhists call our own true nature."

—

This article has been updated from its original and print versions to reflect the fact that former President Biden did not pardon Leonard Peltier, but rather commuted his life sentence to home confinement.

Scott Chaskey's latest book is "Soil and Spirit: Cultivation and Kinship in the Web of Life." He lives in Sag Harbor.