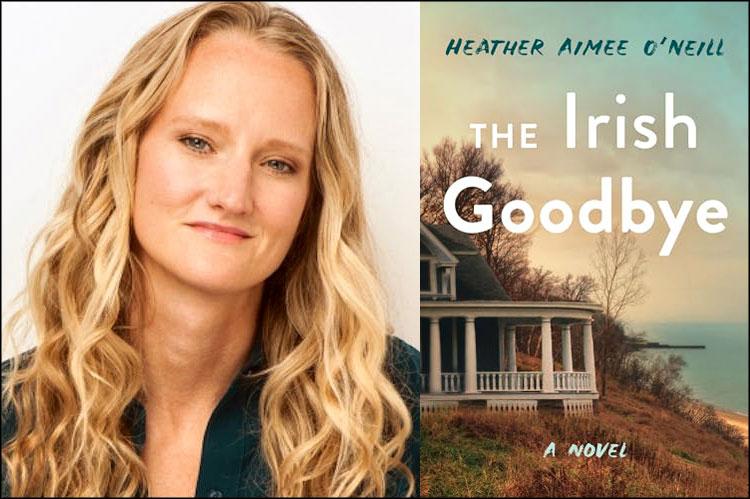

“The Irish Goodbye”

Heather Aimee O’Neill

Henry Holt & Co., $28.99

It’s Thanksgiving 2015 in “The Irish Goodbye” when the Ryan family gathers at their ancestral Victorian home — dubbed The Folly — perched on a peninsula overlooking Peconic Bay in the fictional town of Port Haven, loosely modeled on the North Fork’s Greenport (the author, Heather Aimee O’Neill, grew up in Huntington). It’s the first time they’ve all been together in years. The holiday meal, historically homemade, is now catered with oysters, and three generations of the family come together not only for dinner, but for a reckoning with their shared past.

Three adult daughters — Cait, Alice, and Maggie — arrive with their own complications in tow: grandkids underfoot, a new girlfriend, a recent divorce, an affair, a long-held crush. All of it orbits a tragedy from 25 years earlier, an accident on the boat of the eldest Ryan child, Topher, that killed the brother of his best friend. A lawsuit nearly bankrupted the family, and Topher drifted through odd jobs, drinking, and a depression he never surfaced from before taking his life. “The Irish Goodbye” traces the ripples of loss over three decades — predictable as the bay’s tidal rhythm, yet singular as each wave.

Told in alternating perspectives from the sisters’ points of view and moving between past and present, the novel unfurls with expert pacing, each detail released at just the right moment to preserve suspense, including the satisfying title reveal. It’s a testament to O’Neill’s command of plot that even knowing the broad contours of the story in advance, I was surprised again and again. Every escalation feels earned and entirely plausible. Secrets aren’t just kept carefully between characters, they’re strategically withheld from the reader by O’Neill herself.

As the story is set over a long Thanksgiving weekend during a multi-day snowstorm, one character makes an observation that echoes easily for the reader: “I don’t think I could leave even if I wanted to. . . . It’s like we’re in a snow globe.” But it’s not only the wintry setting that creates this effect. It’s the enclosed, pressurized feel of this timeless souvenir, the fragility of the people inside the house, shaken by accusations, choices, and buried emotions, then briefly settled before the next swirl. The book reminds us that we are all just one shake away from our own storm.

Readers will likely identify with one sister and favor another. Cait, the eldest, is a successful but self-involved London lawyer who speaks her mind but struggles with real connection. Alice, the middle child, is exhausted from caring for both her aging parents and their deteriorating home. Maggie, the youngest, is a boarding school English teacher wrestling with intimacy and acceptance in both her romantic and parental relationships.

O’Neill’s strengths lie equally in macro and micro storytelling — an assured, carefully plotted narrative populated with sensory-rich details. One scene opens with scent: “The smell of incense and coffee followed her as she and Father Kelly made their way through the quiet rectory hallways and into the kitchen.” Another uses taste to show the evolution of a teenage romance: “. . . but his mouth tasted like wine and sage, not beer and weed and Bazooka gum.”

Though the novel features men, it is decidedly estrogen-driven; the women propel the story while the males, including the lost Topher, serve more as catalysts than leads. Despite the cozy backdrop — blankets, baths, hot tea, sweaters — the house remains drafty and cold, and Nora, the matriarch, mirrors it: slow to warm, shaped by her motherless childhood with nuns. “It’s hard to be a mother when you never had one yourself,” she confesses. Yet her marriage with Robert is tender and resilient, a surprisingly steady center amidst chaos and heartache. “Alice had always thought that her parents had a closer relationship with each other than they did with any of their kids” — a refreshingly unusual dynamic in today’s child-centric culture.

As an only child, I read the book intrigued by the combat and comfort of sibling relationships. It’s easy to imagine “The Irish Goodbye” onstage: The dialogue is sharp, intimate, believable; the entrances and exits crackle. O’Neill’s writing is efficient — no sagging scenes or bloated back story. If anything, the voyeur in me craved even sharper edges: more bite, more rawness. The characters could handle it, and I wanted the claws out, especially among the sisters.

All told, I recommend this debut wholeheartedly. This holiday season, curl up with “The Irish Goodbye,” a mug of something warm, and just a light throw — its pages will heat you from the inside out.

Rachel Anne Abrams is a UX designer, writer, and dancer who lives in Brooklyn and Sagaponack. She recently completed a memoir about how movement heals, shaped by her experiences as a dancer and the daughter of two parents diagnosed with Parkinson’s. She is online at rachelink.com.