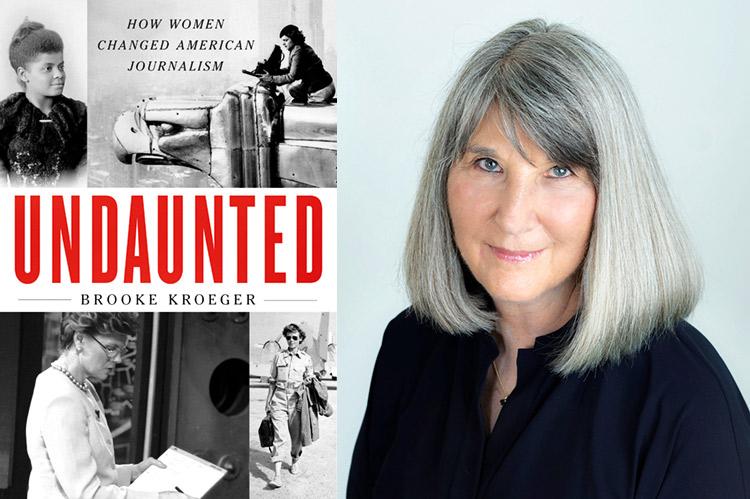

“Undaunted”

Brooke Kroeger

Knopf, $35

We know God made trees, and the birds and the bees. And the seas for the fishes to swim in. We are also aware that he had quite a flair for creating exceptional women. — Noel Coward introducing Marlene Dietrich

Exceptional women are no strangers to American journalism going back almost two centuries. The problem is that they were almost always seen as exceptions, not indicators of what many of their gender could actually do.

Of course, journalism, being part of the society it serves, cannot totally escape sharing — as well as reporting — that society's consciousness, conventions, and prejudices, despite a frequent parallel mission to spotlight injustices and potential corrections. But as women prompted society to broaden its view of their role in work, citizenship, sex, and marriage, journalism too entered a process of change still ongoing.

Women's increasing numbers in, and influence on, American journalism — the recent elevation of two female execs at CNN meant that women now direct or co-direct every major U.S. news network — is the whole point of "Undaunted," by the veteran correspondent, editor, and journalism professor Brooke Kroeger.

So your question now might well be: Why isn't a woman writing this review?

Of course, assignment by gender is one of the traps that women of my profession have so long struggled against. But for whatever reason, I am delighted with the opportunity to celebrate them — especially those I have worked for (primarily Katharine Graham at The Washington Post and Newsweek), worked with (Nora Ephron at old New York Post, Lynn Povich and Liz Peer at Newsweek, Anna Quindlen for the Newsweek radio show), and befriended over six decades (Gail Sheehy, a longtime tennis pal, among others), all of whom figure in the many tales Ms. Kroeger tells of sexist obstacles overcome even before the usual hurdles in creating that "first, rough draft of history," as Boss Lady Graham's late husband defined our calling.

Also I was a not-so-innocent (some might say) bystander to the Great Turning Point on March 16, 1970, when young women researchers at Newsweek filed suit for assignments, pay, titles, and respect equal to what was enjoyed by young male journalists there (like me, then). The settlement helped accelerate equity and womanpower throughout print, broadcast, and subsequent online platforms.

But Ms. Kroeger starts with dense details about those earliest "exceptionals," many of whom were at least as much activists as journalists, digging deeply to expose conditions of inequality and oppression along race, wealth, and gender lines.

Groundbreaking investigations brought fame to Ida Tarbell, on the power and privilege of Big Oil, and to Ida B. Wells, on the scourge of lynching and other mistreatment of Black Americans.

Through the decades, and with poetic justice, such probing and publishing helped promote many reforms, such as the equal employment opportunity laws of which women at Newsweek and other publications took full advantage.

Margaret Fuller — already famous for her "Conversations" about literature and art for women around Boston — in 1840 was named first editor of The Dial, a quarterly magazine launched by Ralph Waldo Emerson, with whom (and his wife) she had tirelessly campaigned to ingratiate herself.

Fuller's 1843 essay "The Great Lawsuit," powerfully arguing for gender equality in education and employment, so caught the attention of Horace Greely (and his wife) that he made her literary editor and second-front columnist for his New York Tribune, the most-read daily of the day, and invited her to live with them.

By 1875, according to Jane Cunningham Croly, a fashion and women's page editor of The World in New York and founder of the Women's Press Club there, 60 U.S. newspapers had women as "editors, editorial writers, and the like [who were] fully as successful as the average man" albeit generally paid less.

With more education and preparation (where was not made clear) Croly saw even better female prospects as family and social life became more appealing subjects to readers and retail advertisers — seen now more as the Prison of Pink Fluff, though feature style has become more common for hard news as cable TV and the internet make basic facts so well known.

Next came an era of "experts, stunts, sobs . . . and Amazons," as Ms. Kroeger describes the 1880s to 1920s, when some women made news just by covering it.

An accomplished equestrian, Midy Morgan from County Cork had connections to New York's horsey set that helped her get assigned by The World to the track at Saratoga Springs: "An Irish Lady's Opinion of . . . American Gentlemen [and] the Races." Which led her to The New York Times for 20 years as livestock markets reporter, including important investigations of animal abuse and its threat to human diets.

Nellie Bly, starting at The Pittsburgh Dispatch, scored with a new form of daring personal reportage — feigning insanity to report on alleged abuse in a New York asylum for The World, traveling solo to beat the fictional triumph of Jules Verne's "Around the World in Eighty Days" (in 72 days, six hours, and 11 minutes).

By 1900, the number of women journalists had nearly doubled over a decade. And war had become an ally, not only by opening up the domestic slots of men in service. Covering a rebellion in Cuba for Hearst's New York Evening Journal in 1896, Kate Masterson made the front page by interviewing Spain's commander there, nicknamed "The Butcher," who talked of machete-wielding female rebels, led her to his bedchamber, and flirted, all of which she reported.

Despite a new popularity for "sob sister" journalism meant to stir emotions, a cadre of "front-page girls" began covering major stories at big city papers, Ms. Kroeger reports. And starting in 1914, some 40 went to cover World War I on assignment or freelance, including Bly "On the Firing Line."

Later in Europe, Dorothy Thompson filed from Berlin as correspondent for The Philadelphia Public Ledger, which led to a column in The New York Times. And The Times ran regular pieces by a freelancer, Anne O'Hare McCormick, for a decade — including a prediction of Mussolini's ascent — before giving her a job and a column.

The Times did not nominate McCormick for a Pulitzer in 1937, but that year she became the first woman to win one, by acclamation of the prize jury. Bad Times.

World War II created more empty slots in journalism for women — by then more than half of all newsroom employees — plus rare respect and renown for some at or near the front.

For Collier's on D-Day, Martha Gellhorn hid on a hospital ship to hit Omaha Beach before all other reporters, including her husband, Ernest Hemingway. Marguerite Higgins, for The Herald Tribune, was one of the first two American correspondents through the gates of the Dachau concentration camp not yet fully liberated.

In the Korean War, Higgins's undeniable daring and allure helped win her a Pulitzer but also drew gripes from many male correspondents, in particular her Herald Tribune colleague, fellow Pulitzer winner, and fiercest competitor, Homer Bigart, later with The Times. Ms. Kroeger confirms what an old Newsweek hand who'd been there recalled about Bigart's reaction when Higgins went home to have a baby. "Who was the mother?" he asked with his trademark stammer. Or sometimes: "Did she eat it?"

In postwar decades many women rose to run desks, departments, and entire editorial staffs around the country, broadening perspectives on issues worth covering (the homeless, powerful sexual harassers). But other women — notably at The Washington Post, Newsweek, and The New York Times — still condemned male domination, too little concern for female needs and families, and solely white men atop the masthead.

Only after Newsweek lost major circulation and status, changing hands several times, did controversial male owners bring a woman back to be global editor in chief — Nancy Cooper, a bright researcher at the magazine in my day.

At The New York Times, with many women already in senior positions, Jill Abramson, the Washington bureau chief, next became managing editor and in 2011 got the top spot — the first female executive editor — only to lose it in 2014 at least in part over backstabbing mismanagement.

Admittedly often abrasive (not so unusual for Times men), Ms. Abramson did not inform the managing editor, Dean Baquet — a Pulitzer winner and thought to be her eventual successor — that she had arranged to hire a second M.E. "A true partner, another woman . . . appealed to me immensely," she later wrote. Mr. Baquet complained to the publisher, Arthur O. Sulzberger Jr., who quickly put him in Ms. Abramson's place, the first non-white ever. But after a few more years, the top spot went to yet another white male. "The More Things Change," Ms. Kroeger smartly titles that chapter.

Yet I feel her sisterly vision shortchanges some noteworthy aspects of her story. Katharine Graham, for example, was "brought up to think men superior . . . but I had to change," she confessed on Newsweek's radio show. Beyond the Newsweek settlement with researchers, she backed ditching The Post's women's pages for a new section called Style, arguably the era's best cultural coverage. And for 20 years the paper's editorial pages were run by a woman, Meg Greenfield, a Pulitzer winner. Not to mention how Kay joined the fight against prior restraint and other government threats with defiant Post coverage of the Pentagon Papers and Watergate.

Not mentioned at all is the heiress Dorothy Schiff's evolution of Alexander Hamilton's New York Post into a bastion of liberal commentary from Eleanor Roosevelt, Mary McGrory, Murray Kempton, and others. And it was there Nora Ephron got to demonstrate writing skills never considered when she clipped papers for Newsweek. The biography of flirty/frosty "Dolly" Schiff is "The Lady Upstairs" by Marilyn Nissenson (reviewed in The Star on Aug. 2, 2007).

Also unmentioned, except in one footnote with two letters (and a period), is the creation and impact of Gloria Steinem's Ms., the national magazine run by women for women (and others who care), "a testament to how far we have progressed in five decades — and a reminder of how far we still must go," it proclaims.

Clearly "undaunted" as well.

Brooke Kroeger has worked for United Press International, Newsday, The New York Times, and New York University. She has a house in East Hampton.

David M. Alpern reported, wrote, or edited at The New York Post, The Daily Journal of Elizabeth, N.J., U.P.I., and Newsweek, running the "Newsweek on Air" and "For Your Ears Only" network radio shows for three decades. He now presents live and Zoom programs for libraries near his home in Sag Harbor.