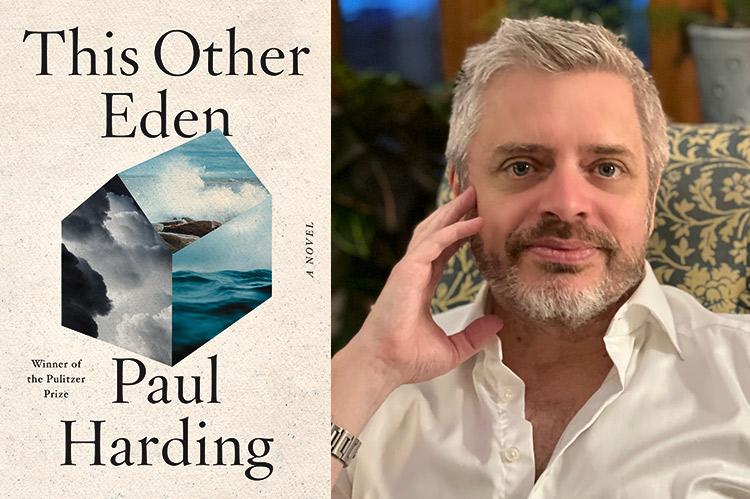

“This Other Eden”

Paul Harding

W.W. Norton, $28

In the first pages of Paul Harding's new novel, "This Other Eden," the reader is introduced to Benjamin Honey, formerly enslaved, and his Irish wife, Patience. As they arrive on a small, uninhabited island off the coast of Maine, Benjamin brings with him a bag of tools and a cache of apple seeds. Soon he has planted and cultivated so many apple trees the spit of land is dubbed Apple Island.

A small settlement begins to form, including whites, Blacks, and Indigenous people. When a hurricane hits the island, Mr. Harding unleashes a tour de force of descriptive power.

"The hurricane roared so loudly Patience Honey thought she'd gone deaf at first, that is, until she heard the tidal mountain avalanching toward them, bristling with houses and ships and trees and people and cows and horses churning inside it, screaming and bursting and lowing and neighing and shattering and heading right for the island."

Mr. Harding won the 2010 Pulitzer Prize for fiction, and did so with one of the most unlikely literary success stories. After being rejected by nearly two dozen publishers, he chanced upon a small one, Bellevue Literary Press, for his novel "Tinkers" — a fiction ostensibly about clock-fixing, and exhibiting his extraordinary lyrical talent. Somehow, this little-known book caught the eye of the Pulitzer board, and the rest is history.

Mr. Harding grew up in rural Massachusetts, and his gift for nature writing — which he employs with an almost holy reverence — will remind many of the New England transcendentalists, who included Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Apple Island is described as being, at its narrowest point, only 300 feet from the mainland, and yet its growing inhabitants seem to eschew modernity in a way that allows the author to luxuriate in the Edenic simplicity of their lives. They farm, stargaze, and gorge on the island's bounty of seafood, all of it captured in Mr. Harding's rich, sensual prose.

Here, for example, are the children getting oysters from a fisherman under the moonlight: "The girls poked the frilled, layered meat and slid it around the smooth insides of the carapaces. The boys sipped from the shells like teacups."

One day a white man named Matthew Diamond arrives on the island. Though the inhabitants are skeptical, his intentions are mostly well meaning — he wants to build a schoolhouse and educate the islanders. These efforts catch the attention of local officials — some of whom are in thrall to the theory of eugenics, which posited, among other odious ideas, that the mixing of races rendered one genetically inferior. And yes, this is going exactly where you think it is.

The novel is based on a real incident from Malaga Island, Maine, which was home to a mixed-race fishing community. In 1912, 47 residents were forcibly removed, some requisitioned to institutions for the "feeble-minded." Mr. Harding loosely follows the historical narrative, embellishing the tragedy by painting a number of vividly realized, and wholly fictionalized, characters.

There is Zachary Hand to God Proverbs, a hermit who lives in the base of a tree and carves Bible scenes on the walls. The white interloper, Matthew Diamond, is portrayed as the quintessential educated man of his era, perhaps well intentioned — he wants the islanders to learn Latin and Shakespeare — but privately suffering from physical "repulsion" at their multiracial countenances. Ethan Honey, who is light-skinned enough to pass for Caucasian, is shipped off to live with a white family to indulge his talent for art — only to be "outed" for his partially African heritage.

It is tempting to read "This Other Eden" as simply a meditation on America's dubious history concerning race — and Mr. Harding certainly dramatizes that here. But the true villain of the novel may not be just racism but "progress" itself. Despite the generosity of Matthew Diamond's efforts, for example, what, you may ask, do the native islanders really need with Latin or Shakespeare? Or is this an expression of Diamond's own vanity?

When the governmental bureaucrats arrive on the island and begin to measure the skulls of the inhabitants with calipers, your repulsion may include not only the ideas of eugenics, but the anti-human component of science itself.

As for its institutions, a character imagines the new life of one of the girls taken from the island and relocated to a school.

"He imagined the girl sitting in a chair in the middle of the big room with big rectangular windows covered with wire grates and radiators five feet high and ten feet wide along the brick walls, clanking and hissing, and steam pipes and water pipes running overhead bracketed to the ceilings . . . and one of the female attendants cutting off the girl's long thin hair until it looked like all the other female students' hair."

Compared to the paradisiacal Apple Island, the "school" the poor girl has entered is more of a prison. The very institutions of civilization, Mr. Harding implies here, may themselves be insane, and it's at this point the reader might begin to ask who exactly are the feeble-minded.

There is a harrowing chapter in which the inhabitants are physically extricated from the island, their homes burned, the land razed for a resort hotel. But if the denouement of "This Other Eden" feels emotionally muted, it may be that Mr. Harding's transcendentalist sensibilities are suggesting something subtler and more timeless even than the tragedy of lost individuals: the disappearing American landscape, our connection to Nature itself.

At its best, "This Other Eden" has the power to make one question the inheritance of modernity.

Kurt Wenzel's novels include "Lit Life" and "Gotham Tragic." He lives in Springs.

Paul Harding is the director of the M.F.A. program in creative writing and literature for Stony Brook Southampton and Manhattan. He lives in East Setauket.