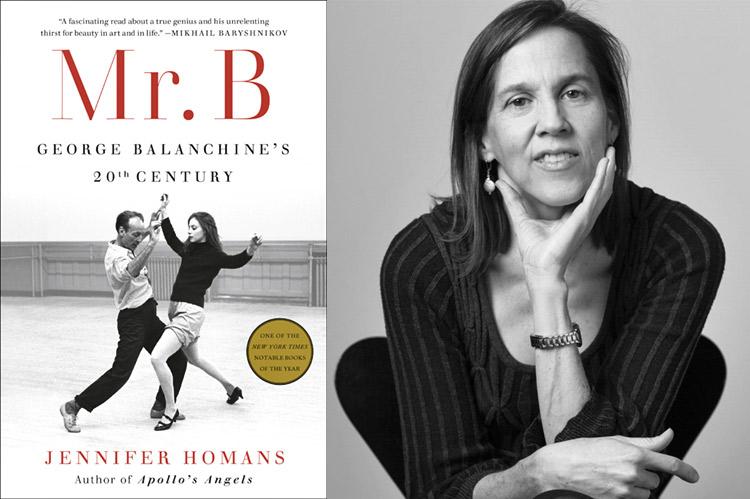

“Mr. B”

Jennifer Homans

Random House, $40

When the history of dance in America is written, some day in the future, its author will have an easier time of it, thanks to Jennifer Homans, whose "Mr. B: George Balanchine's 20th Century" was published late last year.

Without a doubt, Ms. Homans, dance critic for The New Yorker and a Balanchine-trained dancer herself, has given us an important book. It's difficult to imagine that anything significant was omitted from this weighty biography (in both senses) of George Balanchine, the Russian-born choreographer who co-founded and ran, for many years, both the New York City Ballet and its associated School of American Ballet.

As with many comprehensive and impressively researched works of nonfiction, this work can be viewed as many things. Certainly, it is the complex life story of a man who reached the pinnacle of his field and achieved international renown. At the same time, however, it is also a granular examination of its subject's body of work, and moreover an informative cultural history of American ballet during the greater part of the previous century.

In other words, while balletomanes may well absorb every dance and choreography-based fact in this massive book, other readers, who prefer to gloss over the minutiae, will nevertheless be left with an abundance of interesting tales.

Balanchine was born to unwed parents in St. Petersburg, then capital of the Russian Empire, in 1904. His father, Meliton Balanchivadze, was an ethnic Georgian opera singer and composer. The family's humble circumstances improved greatly a few years later, when his mother won the state lottery. (Who would have thought that such a thing even existed in the empire of the czars?)

When the future choreographer was 9 years old, he accompanied his mother when she took his older sister to audition for a spot as a dancer in the Imperial Theater School. To everyone's chagrin, she was rejected, but her brother was invited to audition and was immediately accepted. His mother essentially abandoned her child by leaving him then and there to endure the grim existence and demanding training that nonetheless brought out his talent.

As a young man, he joined the Imperial Ballet. A few years after the Russian Revolution, Balanchine and several other dancers obtained permission from the Soviet state to tour and perform in several European cities. He never lived in his native country again.

Harvard Theater Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University, Photo by Hans Knopf

In Paris, he joined the Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev's celebrated Ballets Russes. (It was Diaghilev who insisted that the young protégé change his surname to something that sounded more French.) Despite his youth, Balanchine was entrusted to create several ballets for the company, which earned him considerable acclaim. Diaghilev was something of a hero to Balanchine, who adopted his mentor's overarching mission to take the best of Russian dance to the rest of the world.

In the early 1930s, Balanchine's work was seen in Paris by Lincoln Kirstein, a fairly wealthy young American arts patron whose father was chairman and a major owner of Filene's Department Store in Boston. ("That young man was Lincoln Kirstein, a young American on his own Diaghilev-like pilgrimage to see culture and art.") Kirstein, who thought that America should produce its own world-class ballet, saw in Balanchine just the person to make that happen. The choreographer accepted his invitation. When he arrived in the United States in 1933, Balanchine, who would always speak an idiosyncratic, pidgin English, knew only three expressions: "Okay kid," "Scram," and "One swell guy."

The two men formed a close working partnership that would last for the rest of Balanchine's life. Together they founded the School of American Ballet in 1934. It would be many years before the school was anything but a precarious undertaking. During that time, Balanchine worked both on Broadway and in Hollywood, creating memorable ballets for stage plays (such as Rodgers and Hart's "On Your Toes" in 1936) and for movies (including "The Goldwyn Follies" of 1938 and "On Your Toes" of 1939).

In 1946, Balanchine and Kirstein co-founded a ballet company, the Ballet Society, which three years later became the New York City Ballet.

It is impossible to separate Kirstein's story from Balanchine's; the former is almost a biography within a biography. Suffice it to say here that Kirstein was a complicated, awkward, high-strung, volatile individual (whose family's chauffeur, we are told, was Dante Sacco, whose father had been famously executed along with Bartolomeo Vanzetti in 1927).

Ballet is often described in terms of physicality. We come away from "Mr. B" with an appreciation of the essential musicality of Balanchine's works. His ballet brought to life the music of a virtual pantheon of early-20th-century composers — perhaps especially Igor Stravinsky.

At the behest of the U.S. Department of State, the New York City Ballet made two Cold War-era trips to the U.S.S.R. The descriptions of these, and the feelings they raised in Balanchine, are powerful reminders of the mind-set of a different era. ("There was no greater enemy in Balanchine's mind than Communist Russia, and it could be said that he positioned his entire life, including his ballets, against it.")

The research behind this biography is most impressive and explains why its publication was the culmination of a 10-year project. Ms. Homans conducted nearly 200 interviews, and the selected bibliography fills some 25 pages, dense with type. She spares no detail in describing the nuances of the choreographer's ballets and introduces her readers to a great many of his dancers, providing their birth names and backgrounds.

Ms. Homans's own background enables her to write authoritatively about every aspect of the ballet world. ("The patterns across the stage are mirrored in the body: front, back, diagonal. Threes repeat almost superstitiously . . . three like the Trinity.") That the author is an admirer of Balanchine is evident. But to her credit, her admiration does not prevent her from seeing and describing the many contradictions of Balanchine's life. He was married and divorced four times and had one common-law relationship; there were also countless affairs with female dancers, whom he would shower with expensive gifts.

Essentially, however, he was a solitary person. He died alone, with no family. The only reason he is buried in Sag Harbor's Oakland Cemetery is that he once had lunch in that village and observed to a friend that it reminded him of the South of France.

Balanchine appreciated the finer things in life, but he lived very simply and had few possessions. He could be very generous to his friends, but when he died, he left nothing to either of the institutions he co-founded and headed. (Perhaps he could not imagine their continuing to exist once he was no longer there.) Although he embraced his dancers like family, he ran his school and his ballet company as an imperious autocrat. He could be compassionate but was also capable of petty jealousy and meanness.

Although Ms. Homans describes Balanchine as something of a loner at his core, she also refers to his "inverse charisma, a quiet inner certainty." Because of this, or perhaps in spite of it, she shows us that Balanchine believed that his mission, and the mission of his ballets, was to teach others how best to live life.

Allow me to go on record: If this book does not come to be labeled the definitive Balanchine biography, I'll be mightily surprised.

Jim Lader, who owned a weekend home in East Hampton for many years, has reviewed books for The Star since 2009.