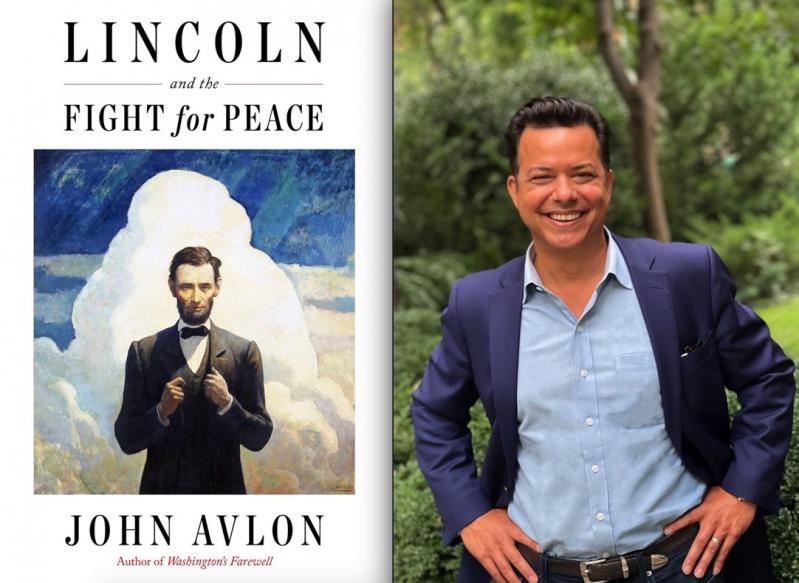

“Lincoln and the Fight for Peace”

John Avlon

Simon & Schuster, $30

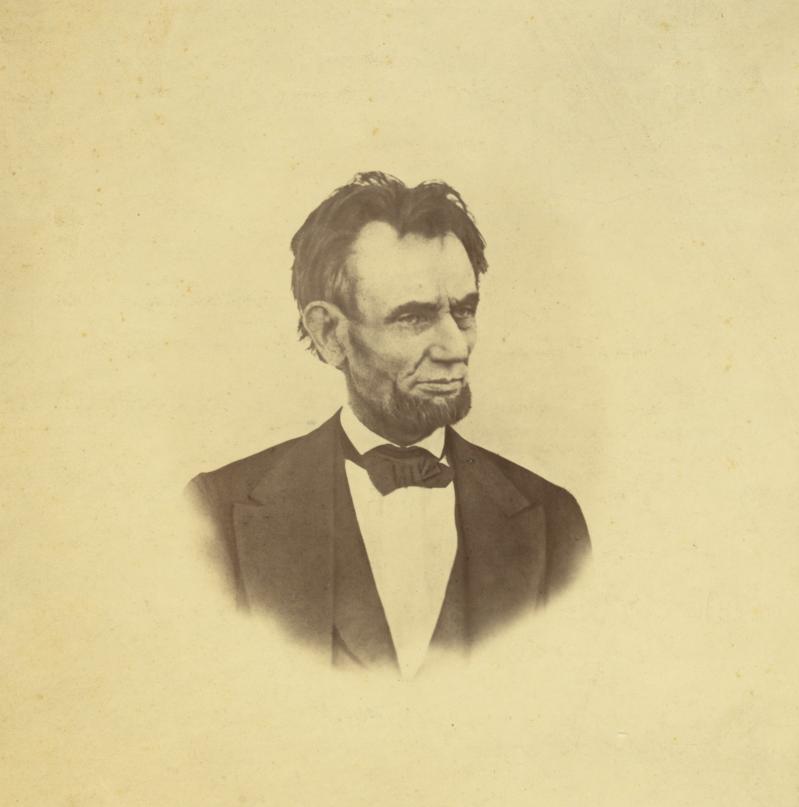

If you are looking for a hopeful take on history in these dark days, this book is for you. In "Lincoln and the Fight for Peace," John Avlon's thesis is that Lincoln's intentions following the Civil War demonstrate the true path to peacemaking after armed conflict. Further, he argues that American leadership following World War II was true to Lincoln's vision. He quotes the closing lines of Lincoln's Second Inaugural Address on March 4, 1865, as the cornerstone of his argument:

"With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation's wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow and his orphan — to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations."

Lincoln's intention was to follow the coming unconditional surrender with a magnanimous peace. Mr. Avlon quotes Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman's memoirs, in which he wrote that Lincoln "was all ready for the civil reorganization of affairs at the South as soon as the war was over. . . . As soon as the rebel armies laid down their arms, and resumed their civil pursuits, they would at once be guaranteed all their rights as citizens of a common country."

But this vision was not to be. As we all know, Abraham Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth — who attended the Second Inauguration — 41 days later. In 1884, Jefferson Davis, the former president of the Confederacy, avowed that "If Mr. Lincoln had lived, the South would have had a President that understood her condition, and he would have been of more benefit to her than any other man could possibly have been."

"In one of the great ironies in American political history," says Mr. Avlon, "the Fifteenth Amendment dramatically increased the political power of the South through full representation in Congress and the electoral college" because "by the fall of 1865, legislatures in the deep South began to implement 'Black Codes' designed to enforce white supremacy in the absence of slavery."

In other words, while 3.9 million African-Americans were now eligible to vote, inflating the census-based number of representatives for the Southern states, the new laws prevented them from voting! Does this sound familiar? Our current politics is full of behaviors reminiscent of Reconstruction as described by Mr. Avlon — behaviors that contravened Lincoln's hopes and wishes for the post-Civil War era and that make domestic aspects of this book relevant today.

Turning to the international arena, Mr. Avlon contrasts the policies of Woodrow Wilson and Harry Truman and their understanding of the Lincoln legacy. Wilson comes off badly in this comparison. Born in 1856 in Virginia and brought up in Georgia, Wilson "presided over the final rollback of Reconstruction by resegregating federal government agencies."

"In the wake of two world wars, two paths to peace emerged. The Lincoln path focused on unconditional surrender followed by a magnanimous peace — reconciliation and rebuilding." Wilson did not demand unconditional surrender by Germany after World War I, however, and succeeded in alienating both his European allies and the American Congress, which refused to ratify his reconstruction plan in the form of the League of Nations.

"Wilson's vast vision was not tempered by Lincoln's modesty or gradualism. He wanted nothing less than to remake the world," writes Mr. Avlon, who chastises him for "a display of hubris."

In sharp contrast, "FDR was steadfast in his insistence on unconditional surrender from Germany and Japan." Of course, it fell to Harry Truman to carry out the conclusion of the wars in Europe and the Pacific after Roosevelt's untimely death, which he did in true Lincolnesque manner, notably with the creation of the Marshall Plan, in the 1948 words of a reporter for The Economist, "an act without peer in history."

The rationale behind the plan, said George Marshall (then Truman's Secretary of State and Defense and formerly Roosevelt's chief of staff coordinating Allied operations), was that Europe "must have substantial additional help, or face economic, social, and political deterioration of a very grave character. . . . It is logical that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace."

Mr. Avlon devotes two chapters to the American postwar occupations of Japan and Germany under Gen. Douglas MacArthur and Gen. Lucius Clay, respectively. These are overly uncritical and nativist in tone. History's view of MacArthur has grown more negative with time, and though Japan has remained a loyal ally of the United States since the occupation, its democracy has been dominated by a single party, the Liberal Democratic Party, with almost no exception since its liberation, and the prewar industrial cartels have been essentially reconstituted.

Nor was the occupation of Germany all sweetness and light. Displaced persons, many of them survivors of Nazi concentration camps, were held in D.P. camps run by the Allies in Germany, Austria, and Italy. "Many of the camps were former concentration camps and German army camps," according to the website of Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center. "Survivors found themselves still living behind barbed wire, still subsisting on inadequate amounts of food, and still suffering from shortages of clothing, medicine, and supplies." The last of these camps were closed in 1952. These people were not taken in by the Allied nations, while many war criminals were reabsorbed into society.

In addition, Mr. Avlon makes it sound as though the postwar order was created single-handedly by the United States. While the Marshall Plan was indeed, in Churchill's words, "the least sordid act in human history," it is incorrect, for instance, to imply — if only by omission — that the U.S. created the European Coal and Steel Community (1951), which was the first step toward a united Europe. The author continues in the same paragraph that "a system of economic interdependence was instituted by linking French and German coal and steel production," marveled at by Konrad Adenauer, the first chancellor of West Germany, as a uniquely American approach to winning the peace.

The E.C.S.C. was the work of Robert Schuman, the French foreign minister, Jean Monnet, the head of French reconstruction planning, and Adenauer. It was a key tenet of the Marshall Plan that the recipient countries should determine for themselves how to deploy the funds offered by the U.S.

These quibbles aside, "Lincoln and the Fight for Peace" is a much-praised and readable book. It would be well that its noble prescriptions be heeded now, soon, and for the foreseeable future.

Ana Daniel taught modern European history at Southampton College. She lives in Bridgehampton.

John Avlon's previous book was "Washington's Farewell." A CNN political analyst, he lives part time in Sag Harbor.