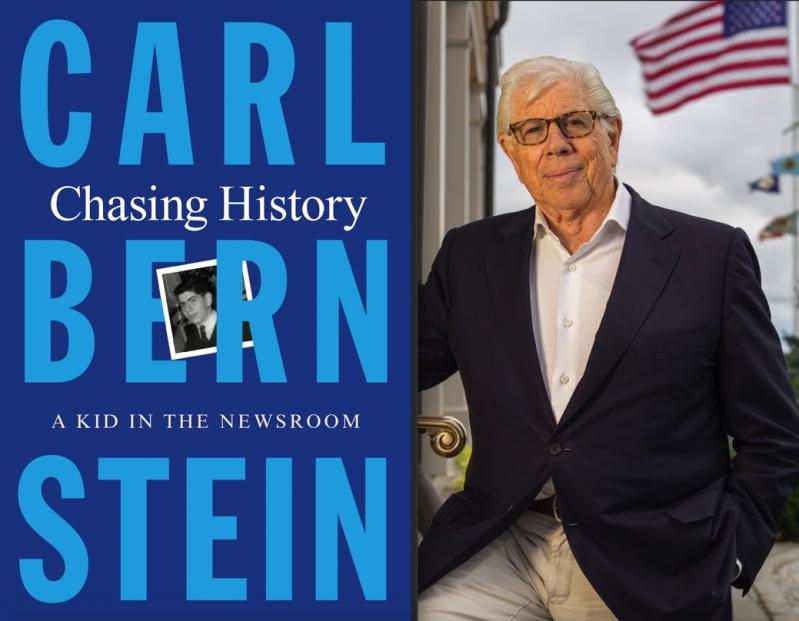

“Chasing History”

Carl Bernstein

Henry Holt & Company, $29.99

It's the First Commandment for any reviewer: Don't write about the book not written — what it could or should have been.

But given who wrote "Chasing History: A Kid in the Newsroom," what he's done — with and to whom — one feels obliged to say straight away what Carl Bernstein's second memoir isn't so no reader is disappointed.

This book contains no previously unpublished gold nugget, no Deeper Throat, from his Pulitzer-winning collaboration with Bob Woodward to corner Richard Nixon over Watergate. (Carl was the better writer, others have reported.)

Nothing on his bedding and wedding of the beloved writer and filmmaker Nora Ephron (a colleague in my own copyboy days at the old, liberal New York Post), nor on the way she portrayed his adultery in her thinly disguised novel "Heartburn," nor on how Jack Nicholson played him in the film version as, one critic wrote, a "shallow creep."

There are no tantalizing tidbits omitted from his earlier biographies of Pope John Paul II and Hillary Clinton. Nor anything on his storied dalliances with such as the ever-luscious Liz Taylor — including in an unheated cottage just across my back hedge in Sag Harbor. (It would be a cold night but a hot time, we were sure, but Liz sent him to Main Street next day for electric blankets, or so their hostess in the big house on Prospect laughed.)

What we have here is Mr. Bernstein's sincere, often heartwarming love letter (maybe overstuffed scrapbook) about his earliest years in the print-era journalism that seduced him at age 16 — as it did me a year older — the frenzy of people and paper, purposeful pounding of typewriter keys, constant clatter of AP, UPI, and other wire service printers, the steady clunk of linotype machines turning written words to column-width lead bars to be nestled into proper place in heavy metal page forms, then the rumble of presses you could hear and feel as they started the run for each new edition. The smell of ink, cigarette, cigar, and pipe smoke (mostly the much-joked-about Prince Albert in a can, as I recall).

"In my whole life I had never heard such glorious chaos or seen such purposeful commotion as I now beheld in that newsroom. By the time I had walked from one end to the other, I knew that I wanted to be a newspaperman," Mr. Bernstein writes of his first visit to the late, lamented Washington Evening Star.

He also delighted in the sense of camaraderie and of "really, my family" that he found at The Star, his hometown afternoon daily, which both structured and thwarted his early career.

In his first memoir, "Loyalties," one reviewer noted, Mr. Bernstein had surfaced a "vast reservoir of anger" and alienation over the brief Communist Party membership of his parents and their continuing leftist activism in the McCarthy "Red Scare" era — for union rights, government workers' rights, civil rights — that drew continuing F.B.I. scrutiny and embarrassing congressional committee interrogations.

But it was thanks to an interview instigated by his dad, who had become a useful source for the Star columnist on government operations, that the paper first harnessed his son's eagerness to the role of copyboy, briskly moving stories or parts of stories from one editor's desk to the next, and other novice chores.

Then it was young Carl's ability to pound out nearly 90 words a minute on the paper's old manual typewriters that promoted him to taking dictation (and real-world lessons in journalism) from top Star reporters on deadline in the field. He'd studied typing in high school with "newspaper work" already somewhere in mind, he recalls, but also because the rest of the class was all female.

Soon he was reporting himself on local stories or parts of larger stories — the J.F.K. inaugural parade (later his assassination and funeral), the Bay of Pigs disaster and Cuban Missile Crisis, the U.S.-Russia space race, the 1963 civil rights March on Washington, racial inequality and friction in the capital city itself — a subject to which Mr. Bernstein had become particularly sensitive, not unlike his folks.

The details in his recollections suggest a near photographic memory or a well-preserved trove of his flip-over journalist notebooks, and a clearly passionate, almost obsessive approach to reporting. Even before his interview at The Star, in a major restaurant near the White House — with money saved on the purchase of a new suit from "No-Label Louie" — he just had to jot down a description of the man in a nearby booth — F.B.I. chief J. Edgar Hoover — "barrel chest . . . small hands."

At The Star, he lived and caroused with young colleagues (plenty of beer and harder stuff in these pages), and paid attention to more experienced ones (David Broder, Haynes Johnson, Mary McGrory, to name a few).

He also cultivated useful sources in all quarters — Black, white, official, civilian — and displayed remarkable initiative. Reading that Senator Barry Goldwater was a devoted amateur radio operator, for example, Carl set up a remote "ham" frequency interview on the eve of Goldwater's G.O.P. presidential nomination. His story made page one.

"Okay, kid," grinned the city editor, Sid Epstein, Mr. Bernstein's ultimate role model, although initially dubious about the idea.

Mr. Bernstein's reminder of the Goldwater "mantra" that led to his landslide loss is more than a bit chilling now — "Extremism in defense of liberty is no vice" — as it seems so resonant with currently polarized politics.

But The Star refused to hire him as a full-time reporter because he had no college degree (nor a notable high school record for that matter), as journalism in the 1960s boosted itself from journeyman's craft to self-styled profession.

Understandably frustrated after five years, he left with a sympathetic Star deputy editor who had just been hired to run New Jersey's Elizabeth Daily Journal, a far more genteel paper, at least when I worked there several years earlier during college summer breaks (and was immediately redressed for rolling up my sleeves as in all the movies: "We don't do that here," the head copyboy warned).

But the city itself was "a reporter's dream" for Mr. Bernstein. "Gentility was not what Elizabeth, New Jersey, was about," he writes. "It was gritty, working class, with a stew of rich ethnic cultures, and — to my mind — it felt a lot more exemplary of America than did the nation's capital city."

Given his choice of assignments and a featured column, he lunched with leading lights, from the mayor and police chief to the local Teamsters Union leader (Tony Provenzano, also a mob boss, whose fatal heart attack struck later at Lompoc Federal Penitentiary in California).

Mr. Bernstein dug deeply into community interests, politics, and problems in a way now fast fading with the death of so many local papers. His story on Elizabeth teenagers getting dangerously drunk across the state line on New York's Staten Island was one of many that won state journalism awards, which helped get him back to D.C. and a job reporting local news for the increasingly dominant Washington Post — including that initially bemusing late-night break-in at a building complex called Watergate.

Which finally moved the kid in the newsroom from chasing history to making it — and unmaking a presidency. But it was his five years at The Star that he says mean most to him.

"Virtually everything of import that occurred afterward in my life as a reporter and as a man — whatever I was able to accomplish, or failed at, or struggled with — had its nascent formation in those years," he writes. "It was a time of amazing change and historic events in the city of my birth and in the nation, and I was lucky enough to share that experience with a group of extraordinary people . . . a colorful, wonderful, happy (generally) lot: the 'heroes' of this book, and of my formative years."

Carl Bernstein has a house on North Haven.

David M. Alpern hosted the "Newsweek on Air" and "For Your Ears Only" radio broadcasts for more than 30 years — including several appearances by Mr. Bernstein — and lives in Sag Harbor, from which he moderates Zoom presentations for local libraries, lately a tribute to John le Carré on the YouTube channel of the Hampton Library in Bridgehampton.