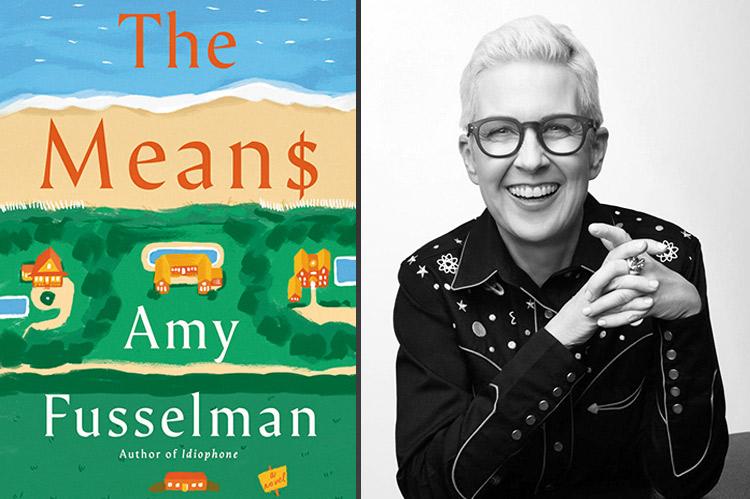

“The Means”

Amy Fusselman

Mariner Books, $27.99

The quirky protagonist of Amy Fusselman's very funny debut novel has one goal in life — an obsession, really: to own a beach house. Her "Must-Haves" feature a musical, self-flushing Japanese toilet and a heated pool.

Shelly Means is a stay-at-home mom, a job that entails managing money, but not making any. Her husband, George, a voice-over artist, is the family breadwinner, so she counts on his income to bankroll her dream. But George's earnings are threatened when he fails to sound believably like a chicken sandwich in a commercial, and the sale of their modest, raccoon-trashed (second) home on a lake garners only enough cash to buy a small piece of land in an enclave called Silver Sound, in Springs, "arguably the most down-market part of East Hampton, the area that contains the dump and has the spottiest phone service." Location, apparently, isn't everything.

Shelly may have only one job, but several other people in her life are multi-taskers. Her dog walker is also a student at the Fashion Institute of Technology, her cleaning person is an aspiring actor, her lawyer doubles as a shaman, and Alice, her C.B.T. therapist, moonlights as a Realtor. In fact, she handles Shelly's anger management issues (suffice it to say she's been banished from the PTA) and her real estate dealings.

In her ardent pursuit of the beach house, Shelly is prepared to make necessary compromises. When Marianne, her architect, suggests building the house with used shipping containers, Shelly eagerly agrees. "We would rescue the containers from their terrible childhood, and then we would take them to the beach to retire."

George is a sensible man, despite his offbeat habit of appropriating "finds" from the trash piles on New York City streets. He wants to sell the land and cut their losses, but Shelly persists, even when Marianne begins to downsize the beach house's proposed specs. Four bedrooms become two, one of which will be divided into a pair of "micro bedrooms," so the Means children won't have to share; the pool will be unheated; the garage reduced to a gravel driveway.

"Listen, it's a beach house," Marianne tells the dubious Shelly and George. "You use it in the summer. You're outside all day long."

Still, Shelly hangs on to her vision of the Japanese toilet, having posted about it on social media, only to be disappointed by the lack of "likes," and some unpleasant comments:

U R TOO DUMB TO USE THIS TOILET

UR TOILET IS ASS

WHY ARE U ALIVE

There's another obstacle, beside public opinion and the financial shortfall, to the fulfillment of Shelly's plans. Her piece of land has an official board of overseers, the Silver Sound Home Aesthetics Committee, who must, according to their bylaws, approve of the beach house. There are emails from Bea, the president of the Silver Sound Homeowner's Association — everyone in Shelly Means's larger world seems to possess only a given name — nixing the shipping container construction.

Shelly, as is her wont, turns to others for advice. Alice, her therapist/Realtor, wears both of her hats with ostensible ease. In one of their virtual therapy sessions, she has Shelly repeat after her the mantras "All is well" and "I radiate love," before telling her to stay on top of the building contractors because "your low-price job won't be a priority for them." She also declares that Bea can't just veto the shipping containers design offhand.

Shelly's lawyer, Tim, agrees, dismissing the housing association as "a bunch of cranks." "I say do whatever you want," is his legal advice, leaving her to wonder "how much that forty-nine-second bit of reassurance cost me."

Jack, Shelly's teenage son, suggests that she write fiction to solve her money problems. He offers his own outline for a young-adult novel, saying, "All you have to do is flesh it out."

Even the family dog, Twix (after the children's favorite candy bar), has an opinion. Yes, she's a talking dog, but not a particularly sympathetic one, despite having "everything you were supposed to give a dog: treats, walks, a raincoat, boots, a Halloween costume, and a microchip." Humorless, sarcastic Twix lectures Shelly on the inequities of the "system," and about starting a revolution around pay for household work. She's a sort of a dour, canine version of Jiminy Cricket.

Then, the Means family's scanty means begin to seem headed toward enhancement. George, who believes his failure at voicing that chicken sandwich may have blocked him from any future work, lands a high-paying gig for a pharmaceutical commercial. All he has to do is intone a list of the "uncommon" side effects of a drug called Placetrex, which "include hemorrhoids, hypnagogic hallucinations, and vascular ischemia caused by thrombosis."

He manages to get through that tongue-twister smoothly, but the ad people make him do it again, only faster. Now he's certain they won't use his rendering, that his career in voice-overs is truly done. And a dreaded meeting with the Silver Springs Home Aesthetics Committee looms. Marianne promises Shelly and George that it's just a formality. She urges them to get started on building their house without waiting for the committee's "inevitable" approval.

The plot takes some truly bizarre turns from here on, but the wry humor is a constant, much of it probably of particular relevance to readers of this paper. " 'I took the jitney,' she said, using the word people in the Hamptons use when they mean 'bus.' " And, Shelly at the town dump: "The paper went into the paper dumpster and the metal and glass in the metal and glass dumpster and the plastic in the plastic dumpster, etc. I did all this while vulture-size seagulls screamed overhead and the stench threatened to overpower me. It was like a preschool interview in hell."

Amy Fusselman's experience as a memoirist, with four nonfiction works to her credit, serves her well in writing fiction. Her first-person heroine is convincingly (although often irrationally) introspective. Unlike Twix, Ms. Fusselman is warmhearted and generous, and reading this novel was as pleasurable as — well, a day at the beach.

Hilma Wolitzer and her husband had a house in Springs for a number of years. Her latest book is "Today a Woman Went Mad in the Supermarket."

Amy Fusselman teaches creative writing at New York University.