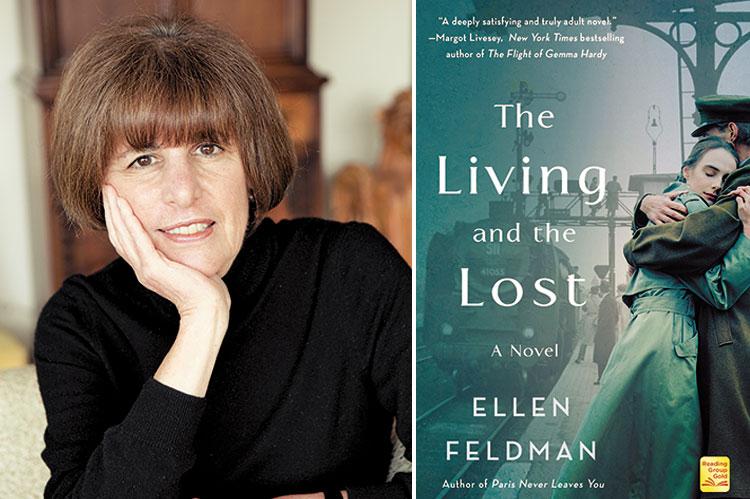

“The Living and the Lost”

Ellen Feldman

St. Martin's Griffin, $17.99

"The Living and the Lost" is a challenging book to read — not because it's impenetrably written like "Ulysses" or "Gravity's Rainbow," though indeed, there are multiple flashbacks and flash-forwards, and a great many characters. But this postmodernish approach is the only way Ellen Feldman could have told her story effectively, with a juicy reveal toward the end that I will only partially give away.

Apart from brief sections in Bryn Mawr and Philadelphia, the action is set in Berlin, in the months immediately following the end of World War II. Berlin is a nightmare, left by the Allies as little more than rubble but populated by millions of desperate people who have made it, the book's narrator tells us, "the reputed crime center of the world, a bombed-out Wild West where drunken soldiers brawled; thieves, murderers, and rapists preyed on the unsuspecting and each other; spies plied their trade; and werewolves, as unrepentant Nazis were called, schemed to rise again."

The Jews had been freed, but "their existence was still a tale . . . of suffering and loss and heartbreak." Every Berliner was peddling something: "heirlooms, weapons, drugs," and "every kind of sex." The occupying Allied troops (mostly Americans, Russians, and Brits) got their pleasure from the "Frauleins," German girls who would do anything for a box of chocolates or a pair of nylons.

The book's central character, Meike Mosbach, was one of the fortunate German Jews who got out in time, physically but not emotionally intact. Her whole respectable but not rich family — father, mother, brother, and sister — had somehow wrangled exit visas, but only two of them escaped to America and a new life before the war, Millie (the American name she adopted) and her younger brother, David.

It was 1935, and the two of them were welcomed by a family of Philadelphia Jews whom they'd never met but who, out of sheer kindness, had agreed to take the whole family in. These kind people had the means to clothe and feed and educate Millie and David. Millie eventually graduated from Bryn Mawr, but after the fighting started, David, like so many other post-adolescent American boys, sneaked off to join the Army.

The first view we get of Millie is distinctly unflattering. The war is over, and she's come back to Germany for revenge, in a "denazification" program run by the Army, poring through endless files and interviewing suspicious German citizens, all of whom claim that they'd hated Hitler, tolerated Jews, and never been associated with the Nazis.

The job allows Millie to exert extreme pressure on suspects, guilty and innocent alike, which she does with great relish because, as she tells everyone who will listen, she hates all Germans (though since she's German herself, this makes problems for her). We see her first in a major's uniform, requisitioning an apartment for herself by evicting a pathetic German widow and her daughter.

"You, your family, and your personal effects must be out by three o'clock tomorrow," she tells the dispossessed woman, sounding a little like a Nazi herself. Those personal effects include a Biedermeier breakfront, which, despite its owner's protestations to the contrary, Millie believes to be genuine and half convinces herself is the same one that graced her parents' living room all those years ago, which reinforces her hatred of its new owner. "Goading a grown woman was fair play," she thinks.

However, inconveniently, her animus against all things German is tempered by an ambivalence that is the mainspring of her personality. "Intimidating a German child was unconscionable," she thinks. "It was easy to hate from a distance. She was surprised to find how much energy it took close up."

Millie's pity is devoted exclusively to little girls in Berlin who live in misery or die or just disappear, and they are in abundance. Her younger sister, Sarah, was one of them, and Millie searches Berlin in vain for word of her and their parents.

Then there's the malnourished child she encounters on a cold day in a park. She shelters her from the wind by opening her coat to her, and later discovers that the girl has stolen the many packs of cigarettes that she uses as bribes and payment in her work. Millie is reunited with her cousin Anna. A broken, beaten survivor, Anna tells her that her daughter Elke has essentially been kidnapped by another woman to whom Anna surrendered her because she could better provide for her, but who now refuses to return her.

It's hard not to think of all these damaged children as sisters of that prime representative of Jewish innocence and Nazi cruelty, Anne Frank.

Almost all the other characters who surround Millie share, to a greater or lesser extent, her feelings about the nation they've subdued: Theo, briefly her lover, nurses a passionate grudge that eventually gets him killed. Her boss, Harry Sutton (who also becomes her lover), appears from his speech and bearing to be an upper-class Brit but turns out to be an American Jew putting on an act. He too has no use for Aryans, but his dislike of Germans in general is more tempered than hers, as is that of David, her brother, an American intelligence officer who tracks her down to her new flat and moves in with her.

Both David and Sutton argue with her about the emotional extremes under which she labors, maintaining futilely that a component of her hatred of Germans must be, since she is a German herself, a destructive self-hatred. She tells them her mission there is to find her parents and sister but they regard this as an idle fantasy: "They're gone," David tells her, like all the other Jews who stayed in the city until they were shipped off to the camps. "How many ways can you find to torture yourself?"

Toward the end of the book, after two traumatic episodes in the train station from which she and David had departed as children, she has what she calls an epiphany (which sounds very much like an orgasm, as Millie describes it) that she is dominated by guilt and shame for acts that she did indeed commit but that were hardly a unique failing; everyone else had committed them too, simply in order to survive.

She forgives herself, marries, and moves back to the States, but the ending is bittersweet; a whole host of new problems await her, including the glass ceiling that makes professional success next to impossible and the return of her ambivalence, this time over the question of whether to become pregnant.

What Ms. Feldman has given us is a deep and nuanced portrait of a complicated woman searching for solutions to problems for which there are no solutions, only topical remedies. In addition, the picture she paints for us both of Berlin and of Jewry at a critical moment in their existence is both believable and well-documented history and a dramatic saga as well.

It's surprising to discover that a book with a subject as gritty as this should be written in such graceful prose. "The Living and the Lost" is a book that should appeal to anyone with a willingness to be moved and entertained by an unusually poignant, if occasionally painful, war story.

Richard Horwich taught English at Brooklyn College and New York University. He lives in East Hampton.

Ellen Feldman's previous novel was "Paris Never Leaves You." She lives in New York City and East Hampton.