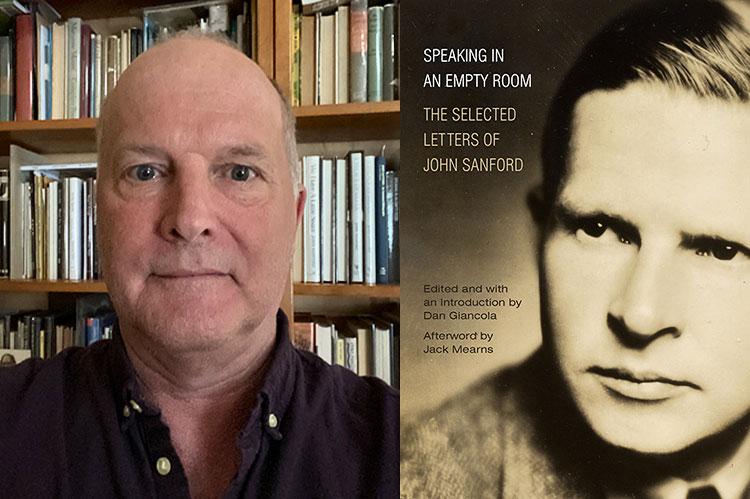

“Speaking in an Empty Room”

Edited by Dan Giancola

Tough Poets Press, $18.99

It would be hard to imagine a more pugnacious epistolary sampling than "Speaking in an Empty Room: The Collected Letters of John Sanford." Between its pages we observe over 70 years of a novelist lashing out at publishers, chiding family members, settling scores with enemies and erstwhile friends, and excoriating middling writers who dare seek his advice.

"All in all, these letters fascinate," argues Dan Giancola in his introduction (he also edited this collection). Whether or not you accept this — or too often find these letters gruff, didactic, and expressing a sourness born of disappointment — will probably rest with your estimation of Sanford as a writer.

John Sanford, who lived and wrote into his 90s, was known as a "writer's writer," which roughly translates as an author with an exacting dedication to craft matched with poor sales. These letters certainly display the author's allegiance to carefully wrought sentences. Even when he is enraged, which is often, there is not a careless phrase or poorly chosen word. It is as if Sanford was incapable of releasing a single sentence that was not rigorously constructed.

For whatever reason, however, he never connected with a large audience. This prompted him to have to scramble for a new publisher with each new book — the search for which these letters cover in the greatest minutia. In them you will learn the names of nearly every major literary editor from the years 1930 onward, hear the impending lunch meetings, and watch Sanford suffer the reply to the subsequent galley submissions (often a resounding no).

Not that Sanford took rejection lying down. When his first novel, "The Water Wheel," flops, he says of his publisher, "he's mismanaged [it] so that he should be ashamed to look an author in the face. . . . I'm going down to see Green to tell him what I think of the whole bloody thing."

When another editor rejects "A Man Without Shoes" because he thinks it won't sell, Sanford goes on the attack: "I wasn't writing merchandise, and I didn't think you were peddling it. . . . I had the dream it was your absolute duty to insure that I be heard." This is so fundamentally romantic and misguided a view of publishing that it speaks for itself.

Literary agents too do not escape his wrath. When one of them, Mel Friedman, informs Sanford that a publisher has agreed to his latest novel, though with major cuts, the author lets him have it.

Dear Mel.

Your letter was a cold sheet of paper, no doubt the wrapping off that stiff hunk of meat you call a heart.

But that you piss ice water is no new thing. What [is new is] your sudden appearance on the side of the publishers, spouting their advice on how to improve a book: cut the balls off, draw the blood, pull the teeth, and strangle it, and we'll be glad to print it.

Get another boy. And while I'm on the subject, I think I'll get another myself. Please return my manuscript.

Sincerely,

"Sanford and Friedman seem to have had many falling outs," Mr. Giancola says in his preface to this letter. You don't say? Still, one admires the sharp economy of the insult.

He is even more brash in his early letters, where the crusty Sanford "charm" is on full display. He writes to his sister, Ruth, about feigning to shop in a Madrid music store. "The dopes fell for it and gave me the run of the place, thinking that I was about to place an order for a million pesetas worth of records." Women, he concludes, "are screwy from the word go."

In a Paris restaurant, Sanford asks a waiter to find out if a fellow diner is James Joyce. When the server complies and asks the man directly (it is in fact Joyce), an embarrassed Sanford calls the waiter a "flunky."

The letters to his sister are often tender but also occasionally cruel, as evinced by this dispatch from 1937: "I've done pretty well . . . and it's a great mystery to me how you have refrained from acquiring just the smallest amount of respect for that success, especially in the face of your own complete failure."

His estimation of other writers, especially the so-called "successful," are predictably harsh. Sanford reads the first page of E.L. Doctorow's debut novel and dismisses it as "176 pages of garbage." James M. Cain, John O'Hara, and Norman Mailer all get the backhand. On the death of Nathanael West, a contemporary and friend, Sanford estimates him "a respectable writer just beginning to grow." This of the author of "Miss Lonelyhearts" and "The Day of the Locust."

Unsurprisingly, his advice to aspiring writers tended toward tough love. Most difficult to read are those to Eli Jaffe, who keeps returning to Sanford for advice on his latest work, despite repeatedly being filleted like a wild salmon. "The book doesn't succeed here and there, it isn't a near miss, it doesn't give promise: it's a failure from end to end." And "You're a surgeon who never bothered to study anatomy . . . it has no reason to having been written."

In subsequent letters, Sanford will apologize, then flay Jaffe all over again, until their relationship becomes a study in literary sadomasochism.

Was there joy in John Sanford's life? Love? His years as a screenwriter in Hollywood show him in his best mood, still kvetching about art and his newest publisher, but manifesting genuine wonder at being championed by Joan Crawford, who took a liking to him, and dinners with Gary Cooper. Some of his best writing is to be found here, primarily on the craft of movie dramatization. "A screenplay is a sort of marionette in repose; it comes to life, and therefore is either good or bad, only when the strings are pulled. . . ."

His letters to his wife, Marguerite Roberts, also a screenwriter, are gushing, many of them beginning with "Most adored wife." It seems a true and enduring love affair, and Marguerite must have been a saint to have navigated this most prickly of personalities. Later, when Sanford outlives her, his letters are heartbreaking in their desolation.

In true Sanford fashion, however, their Hollywood years ended sourly. He and Marguerite were the victims of McCarthyism, blacklisted for the better part of a decade. We get a few letters to Frank Capra on the subject — Sanford believes he was removed from writing the narration of a Capra World War II documentary for being a socialist (precisely why he was removed is unclear from these letters). One wishes there was more material from the blacklist period, where the author's patented invective could have been more justly aimed.

By the end we see Sanford working into his 10th decade — and still sparring with publishers. Self-awareness, however, seems to have eluded him still: "For some shithead reason, I'm in my publisher's doghouse," he writes at age 89. "He hasn't written to me in four months, nor has any of his staff, no doubt at his order." What preceded this one can only guess.

Ultimately what we come away with in these letters is a writer's dogged determination to write and be read. Too often, though, readers of these letters are asked to track, with exhaustive focus, the fate of books that after more than half a century have still not found purchase in the public consciousness. And which have almost completely fallen out of print.

Maybe then it's time for a Sanford revival; the Library of America series seems a ripe landing place for a handful of his best novels. It is difficult, however, to warm up to the truculent personality on display here.

About his literary career, Sanford writes that he sometimes felt as if he were "speaking in an empty room." Judging from these letters, it might be because he cleared it.

Kurt Wenzel is the author of the novels "Lit Life," "Gotham Tragic," and "Exposure." He lives in Springs.

Dan Giancola is a poet and regular poetry reviewer for The Star. He recently retired from teaching English at Suffolk Community College and lives in Mastic.