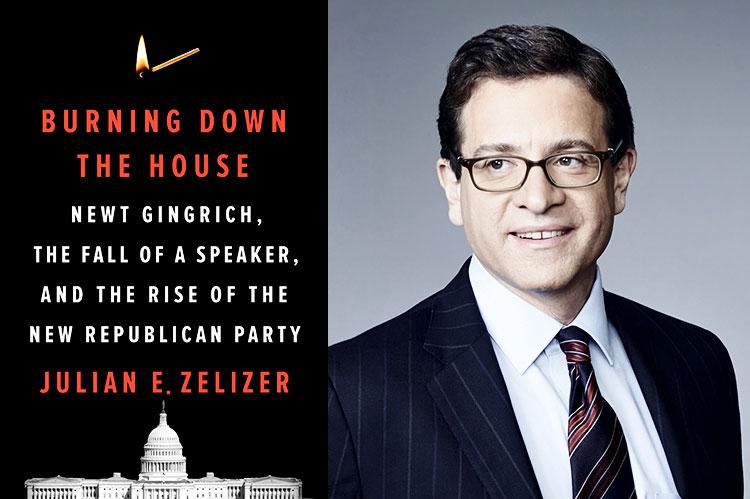

“Burning Down the House”

Julian E. Zelizer

Penguin Press, $30

How in the world did Donald Trump seduce, enslave, or essentially transform the Grand Old Party — as staid, sensible Republicans once called it?

The truth is that the party had for decades been pulled, pushed, prepped, some might say pimped, toward what would emerge as Mr. Trump's style of conservative politics — angry, accusatory, provoking conflict over compromise, distorting or ignoring inconvenient truth for the sake of power.

"We've seen this coming," President Obama told one biographer after the 2016 votes were in. "Donald Trump is not an outlier; he is a culmination, a logical conclusion of the rhetoric and tactics of the Republican Party for the past 10, 15, 20 years. . . . There were no governing principles, there was no one to say, 'No, this is going too far, this isn't what we stand for.' "

Many factors advanced the evolution, among them the rise of a politicized religious right, ruthless partisan gerrymandering, an increasingly market-driven, therefore scandal-hungry mainstream media, and pervasive internet platforms that permit like-minded Americans to see the world almost solely through the particular ideological lens they prefer, to share aggrievement and provocations to greater rage.

Republicans also were furious over the wipeout of Barry Goldwater, elated by the triumph of Ronald Reagan, and increasingly energized by both. But in "Burning Down the House," Julian Zelizer, a Princeton professor, makes a detailed and compelling case that it was the G.O.P. firebrand Newt Gingrich whose approach to politics on the congressional level — hammering away at corruption in the long-entrenched Democratic majority, shattering institutional traditions of comity, civility, and mutual tolerance — most prefigured and paved the way for Mr. Trump's.

Indeed Newt's playbook proved so successful at demonizing and defeating Democrats that an older generation of Republican leaders, holding their noses or not, went along to enjoy control of the House after decades in the minority.

"As the brash young 1980s maverick with the chubby baby face and the helmet of prematurely graying hair," Mr. Zelizer writes, "Gingrich had a central insight: the transformative changes of the Watergate era — with stricter rules to constrain the power of elected officials and congressional reforms that opened up Congress to public scrutiny [and that of Watergate wannabe reporters] — could be used to fundamentally destabilize the entire political establishment and benefit insurgents, including Republicans," despite their rightful shame over Richard Nixon's Watergate downfall.

A former friend and adviser, L.H. Carter, was less flattering. "The important thing you have to understand about Newt Gingrich is that he is amoral," he told the author of a November 1984 Mother Jones magazine article that recapped the Gingrich arrogance, callousness, and marital infidelity — infamously negotiating divorce terms with the first of his three wives (his former high school geometry teacher) in her hospital room after cancer surgery.

Of course even monsters can be cute as cubs. Mr. Zelizer tells of preteen Newt taking a bus from his family's modest apartment in Hummelstown, Pa., to Harrisburg to see two documentaries about African wildlife that prompted him to wonder why that city didn't have a zoo — then to visit City Hall and suggest one.

"An 11-year-old is fighting in City Hall here in an attempt to establish a zoo in the city's Wildwood Park," said a story in the Harrisburg Home Star, then on the AP wire, though that first attempt to influence government failed.

When his stepfather, an Army lieutenant colonel, was later assigned to France, Newt visited the World War I battlefield at Verdun. He was "deeply moved" by the barbed wire, trenches, and bones of the dead, "as well as the ongoing threats to democracy," Mr. Zelizer writes, and began to see politics "as an epic struggle between good and evil."

Back in the U.S., Lt. Col. Gingrich was stationed at Fort Benning in Columbus, Ga., but Newt spent the summer of 1960 with family back in Pennsylvania, where the Harrisburg editor who wrote his zoo story found him starter jobs in radio and TV, and took him to lunches with local pols and lobbyists.

Inspired to volunteer for the Nixon presidential campaign, he was disappointed by the narrow victory of J.F.K. and, as a student at Emory University two years later, founded a Young Republicans chapter there. In the 1968 presidential primaries, he campaigned for Nelson Rockefeller, the losing moderate, but was again inspired by Nixon and conservative Republicans' return to the White House.

Typically, it was strategy and tactics that most attracted Mr. Gingrich. And he set out to master them in Georgia's Sixth Congressional District while teaching at West Georgia College there, targeting John Flynt, a white-haired, war hero, racist Dixiecrat incumbent (since 1945).

In two successive campaigns, Mr. Gingrich tried to exploit rising anti-Establishment sentiment, a growing African-American vote, and some ethical clouds over Flynt's real estate and political dealings. He lost both races but started winning national media attention with his undaunted efforts, evidence that Republicans "can recruit young, attractive candidates [and] challenge even Democratic incumbents head-on," said a story in The Christian Science Monitor.

In 1978, after Flynt retired, Mr. Gingrich finally turned the district Republican with backing from the national party, a more conservative approach, better suits, and smaller sideburns. He also smeared his Democratic opponent as a "homewrecking" feminist because she said she'd commute to Congress to avoid inconveniencing her husband and kids.

In Congress, Mr. Gingrich quickly found another veteran Democrat to club with corruption charges: the prominent civil rights leader Charles Diggs of Detroit, a founder of the Congressional Black Caucus, who had been re-elected despite his indictment and conviction on a variety of charges, including mail fraud and falsification of payroll forms.

Newt mobilized sufficient support from junior Republicans (and two Democrats) to launch a preliminary probe by the House Ethics Committee. He demanded Diggs's expulsion, settled for a near-unanimous vote for his formal censure, and gloried in his resignation after the Supreme Court rejected Diggs's appeal on the criminal verdict.

Promoted to Minority Whip after Reagan's 1980 victory, Newt's greatest victory was forcing the resignation of Speaker Jim Wright of Texas, even before the House Ethics Committee had reached any conclusion on hazy allegations involving the top Democrat's family financial dealings over the years.

Newt's attack also benefited from a firestorm over one of Wright's top aides, John Mack, who years earlier had been convicted of near-fatally hammering and slashing a young woman, later explaining: "Just blew my cool for a second." More than that, Mack had been released from prison to the custody of his brother, who was then Wright's son-in-law.

The Speaker painfully concluded he should remove himself, his family, and his party from the line of fire, emotionally informing the House he so loved that his exit should "bring this period of mindless cannibalism to an end."

It didn't, though the pendulum ultimately did swing against Mr. Gingrich. As Speaker himself, and Time "Man of the Year," after Republicans won the House in 1994, he was key to several government shutdowns and to impeachment proceedings against President Bill Clinton in the Monica Lewinsky scandal, which only boosted Mr. Clinton's poll ratings and his re-election.

When Republican House candidates in 1998 were punished at the polls for such overreaching, among other issues, Mr. Gingrich was forced to step down as Speaker, and soon after resign. He had already been outed in a sex scandal of his own, become the first Speaker formally reprimanded for House ethics violations, and been fined $300,000.

His 2012 presidential bid was a flop. But in July of 2016, Newt was delighted to make Mr. Trump's list of possible running mates, though he wondered in a Fox TV interview if he and the nominee were too much alike, if a "two-pirate ticket" was the wisest choice, and if Mike Pence might be a better stabilizing force.

"Whatever the next few days brought," Mr. Zelizer writes, "Trump was thriving in the political world that Gingrich had created. Gingrich would always be Michelangelo to Trump's 'David.' "

Not an image I care to conjure (even if "David" and Donald may actually share one small "imperfection"). But while Michelangelo's masterpiece endures and enraptures, the 2018 midterms and current polling indicate mounting rejection of the tactics both Newt and Mr. Trump favor, the kind of media-delighting overreach they both enjoy, and Mr. Trump's actual effectiveness as a leader.

Newt finally fell from grace, or at least official power, though his provocations continue online and on Fox. The great Covid crisis of 2020 and November's vote may decide if Mr. Trump follows the same trajectory, or worse.

Julian Zelizer is a professor of history and public affairs at Princeton, a CNN political analyst, and the author of books about Lyndon Johnson, Ronald Reagan, and Jimmy Carter, among others. He has a house in Sag Harbor.

David M. Alpern ran the "Newsweek On Air" and "For Your Ears Only" radio shows for more than 30 years (on which Mr. Zelizer was often a guest), hosted weekly podcasts for World Policy Journal, and now moderates programs for the libraries in Southampton and Sag Harbor, where he lives.