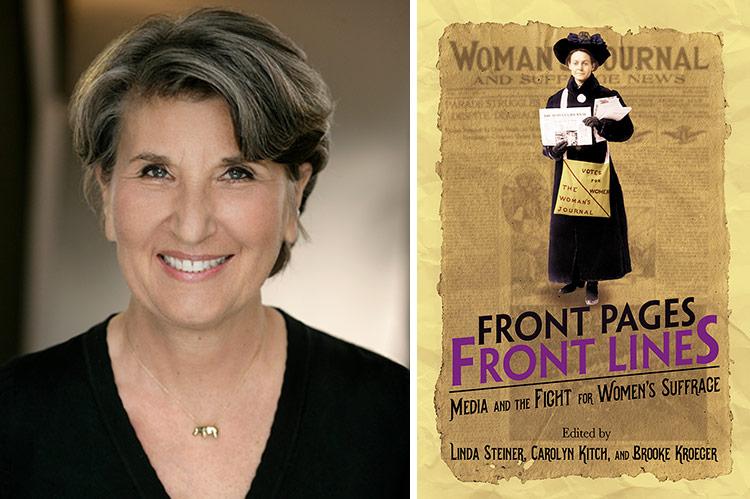

“Front Pages, Front Lines”

Edited by Linda Steiner, Carolyn Kitch, and Brooke Kroeger

University of Illinois Press, $25

One hundred years ago, on Aug. 18, 1920, the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified. It reads: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

Period. End of story?

“Front Pages, Front Lines” is a compendium of essays about the relationship between journalism and the women’s suffrage movement, but it is more than that. It is also a corrective of that reporting and what really happened. Between the lines, it is an analysis of the support of and the opposition to women’s rights up to our own day as the pursuit of the Equal Rights Amendment recapitulates, in many ways, the struggle for women’s suffrage: “One conclusion that can be drawn from this study is that the press and the public might develop a different memory of American women’s political activism if we were to understand it as an ongoing process — not a series of separate episodes about achievers or ‘angries,’ but a continuous story with many coexisting characters and themes.”

Many of the weaknesses of the original movement persist today, for example, “that white middle-class women suffrage leaders failed to embrace women of color and to partner with them.” Oppositional arguments persist to the effect that female activists were “restless, abnormal women who seem to have a perverted and diseased ambition to do anything and everything except those things which God and nature designed them to do,” as a Republican representative from Massachusetts said in 1917.

From Time’s first “Women of the Year” issue in 1975, Brooke Kroeger quotes the following: “A measure of just how far the idea has come can be seen in the many women who denigrate the militant feminist style (‘too shrill, unfeminine’)” and cover stories of the 1980s and 1990s in the same publication “that repeatedly cautioned that women were frazzled by trying to ‘have it all’ and announced the ‘news’ that feminism was dead, most notably on a 1998 cover featuring the disembodied heads of Susan B. Anthony, Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem . . . who stood for ‘the culture of celebrity and self-obsession’ into which feminism had sunk.”

This story has personal significance to this reviewer. In 1969, five months pregnant, I was hired by a money-center bank into a research position. I had left my previous job in what we then called “the female ghetto” because at five months a pregnancy was considered a health liability. Ironically, though I had been hired by a bank, I could not at the time open a bank account in my own name without my husband’s permission. I was 31 years old and it was 50 years since the passing of the 19th Amendment. I was incredulous at being offered this opportunity and found myself a lone woman in the junior officers’ dining room but otherwise allowed to be “one of the boys.”

That was the “miracle” that launched me into the world of men-only professions, where for the next 30 years I was mostly the only woman in the room. It was only in the 1980s that young women graduates of law and business schools began to enter these professions in significant numbers.

Carolyn Kitch reports in “Front Pages, Front Lines” that in 1970 Alice Paul, one of the champions of the suffrage movement, on the 50th anniversary of the 19th Amendment, said to Life magazine, “The movement for women’s rights has been going on for years and years. . . . There are generations of women who have brought it up to this point.”

Yet the Equal Rights Amendment has not yet been added to the Constitution. It would read: “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” Note that the word “women” does not appear in this text — it does not appear in any of our founding documents. The statement is benign and neutral.

Opposition still rests on two stale arguments: one, starting in 1972 with Phyllis Schlafly — she was a member of the John Birch Society — that the E.R.A. would take away gender-specific privileges currently enjoyed by women, including “dependent wife” benefits under Social Security, separate restrooms, exemption from the draft, alimony, child support, and a raft of family values; the second that women have made so much progress since 1917 that the E.R.A. is no longer necessary and/or that it is already covered by the 14th Amendment.

So, period. End of story?

Ana Daniel, a graduate of Stony Brook Southampton’s M.F.A. program, is retired from business and teaching. She lives in Bridgehampton.

Brooke Kroeger is a professor of journalism at New York University and the author of “The Suffragents: How Women Used Men to Get the Vote.” She lives part time in East Hampton.