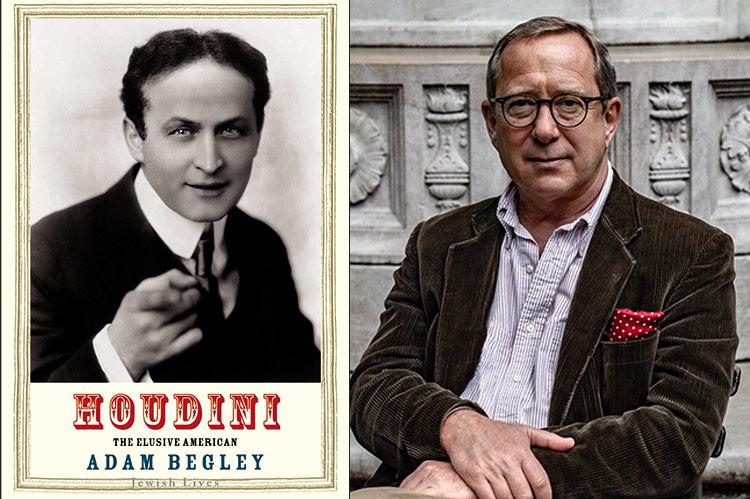

“Houdini: The Elusive American”

Adam Begley

Yale University Press, $26

When he died at the age of 52 of peritonitis, after willfully ignoring the days of searing pain and raging fever that issued from his burst appendix, Harry Houdini had achieved all of his monumental ambitions. He was an international superstar, a celebrated magician and escape artist, a master of public spectacles, a movie star, a pioneering aviator, the author of multiple books (with a little help from his ghostwriter friends), and America’s premier investigator of the paranormal.

Yet at the end of his life, with fame and glory and more money than he could possibly need, he continued to subject himself to the grueling punishment and self-torture that made him famous, until it killed him.

“What kind of man was this?” Adam Begley asks in his splendid new biography, “Houdini: The Elusive American.” Houdini was a master of self-invention, blending the facts of his life with gross exaggerations and biographical fantasies, all of which Mr. Begley deftly untangles, offering the reader a visceral sense of this deeply mysterious, driven, egomaniacal genius of a man. The book is part of the Yale University Press’s “Jewish Lives” series.

In the early pages, Mr. Begley sets out the incidents that were to shape Houdini’s character and launch his career. Born Ehrich Weiss in Budapest on March 24, 1874, Houdini came to America at the age of 4, accompanied by his mother and four brothers, and settled in Appleton, Wis., where his father, a rabbi, led a small congregation. After four idyllic years, Rabbi Weiss was summarily fired and never found meaningful work again. Destitute, the family moved to New York, where the rabbi, a beaten man, ended up cutting necktie linings in the rag district, along with his son.

From his father, young Ehrich inherited a dual legacy, a love of books and learning and a terror of failure. “The son saw the father’s failure as a trap,” Mr. Begley writes. “Avoiding that trap was at first a reflex, the earliest stirring of his impulse to escape — the impulse that transformed him into his ideal self, a world-famous unbeatable American superhero.”

The way out of the trap — as it was for many Jewish immigrants — was show business. (“As Minnie Marx famously explained when asked why she sent her sons into show business: ‘Where else can people who don’t know anything make so much money?’ ”) Already a crack athlete, the teenage Ehrich Weiss put together a magic act and, taking his name from the innovative French conjuror Robert-Houdin, went on the road with a pal as the Houdini Brothers. It was while playing Coney Island that Harry met and quickly married a petite, Catholic, 18-year-old singer and dancer named Beatrice (Bess) Rahner, and the Houdini Brothers begat the Great Houdinis.

For five years the Houdinis struggled, playing dime museums and beer halls, earning barely enough to stay afloat. Although he had little education, perhaps finishing third grade, Houdini was a prolific writer, leaving behind diaries, journals, and thousands of letters, which Mr. Begley draws upon throughout the book.

For several months, the Houdinis joined with the Welsh Brothers Circus, where, Mr. Begley tells us, Harry’s Jewishness and immigrant identity set him apart and heightened his desire for assimilation and recognition as an American (he worked diligently to erase his accent and later had his passport altered to claim Appleton as his birthplace). Yet, paradoxically, he felt at home among circus people, his fellow outsiders.

Houdini got his big break in 1899, when he was seen by the theatrical agent (and fellow Jewish immigrant) Martin Beck. Impressed by a handcuff escape Harry had added to the act, Beck offered him a contract, with the understanding that he concentrate on escapes, not magic. It was prescient advice. Within a year, Houdini was a vaudeville headliner, earning more money than he had ever dreamed of.

Part of his meteoric ascent was due to the novelty of the act. Who knew audiences would find it thrilling to watch a man get trussed up in ropes, cuffs, and chains, and then struggle mightily to get free? But just as central was his genius for self-promotion. In cities where he was booked, he would challenge law enforcement to cuff him, toss him in a cell, and throw away the key. And to rule out any suspicion he might be hiding a key, he took to performing these escapes stark naked (for male eyes only).

The media ate it up. The jailbreaks garnered headlines — illustrated with photos of a near-naked Houdini, handsome, muscular, weighted down by cuffs, chains, and leg irons (many of these photos are in the book) — and the headlines packed the theaters. It was a formula he would use his entire career: confrontation, struggle, adversity, triumph.

Following his American success, Houdini embarked on a triumphant four-year tour of Europe, Russia, and Australia. He also doubled down on his taunting of authority, as when, while playing Moscow, he challenged the tsar’s dreaded police to lock him — naked, of course — in what was called a “Siberian transport cell,” used to send prisoners to the gulag. Naturally he escaped, writing, “I am the first person who has ever dared them.”

Interspersed with these accounts of Houdini’s public performances are more intimate portraits of his domestic life, and his devotion to his mother, Cecilia. It was also during this period that, dripping with money, he began seeking out and shipping home the thousands of books and pamphlets that would become his extraordinary library devoted to theater, magic, and the occult.

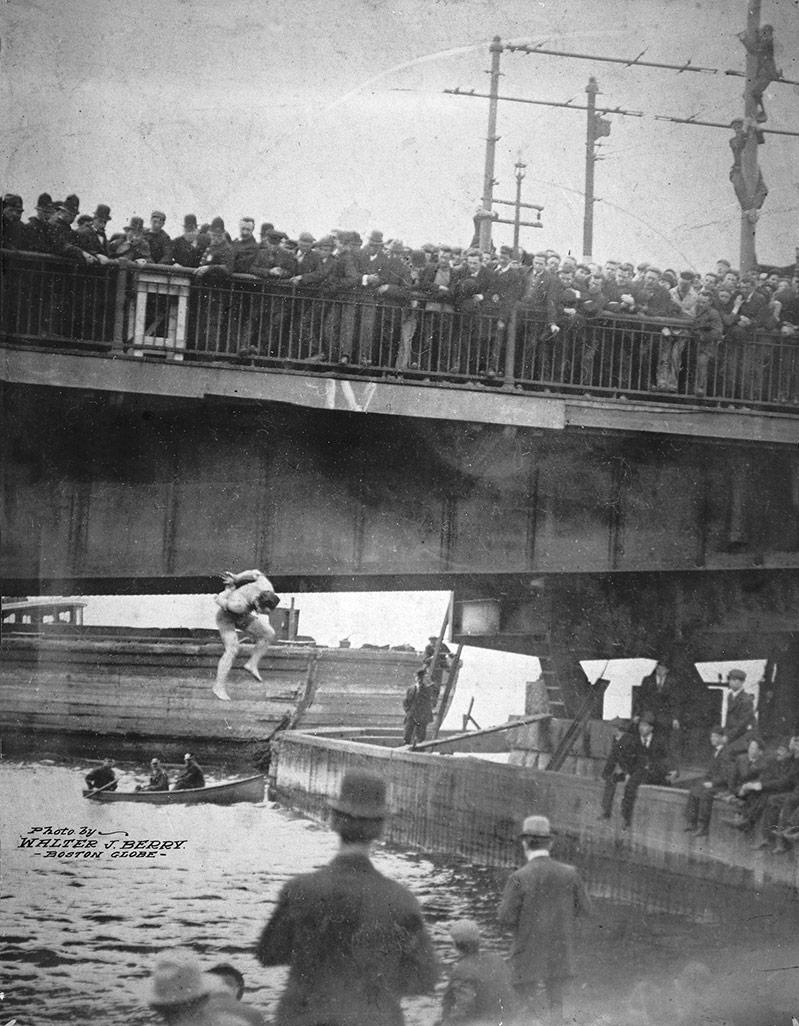

Returning to the States, Houdini launched his literary and film careers, publishing, among other works, a vicious denunciation of his onetime idol, Robert-Houdin, an act Mr. Begley describes as literary patricide. The book was not well received, but no matter. Houdini shifted his career into overdrive with a new series of death-defying stunts that Mr. Begley, a masterful writer, describes in thrilling detail: Houdini hurling himself off bridges into frigid rivers, hands cuffed behind his back, or submerged headfirst in the coffin-sized Water Torture Cell, which “reeked of menace,” and from which he emerged “gasping, eyes bloodshot, lips flecked with foam.”

Houdini’s career entered a new phase when he became the central figure in a national controversy surrounding spiritualism — the belief that the dead could speak to the living through the agency of a medium. Spiritualism had been around for decades but experienced a resurgence after World War I, when a new crop of fraudulent mediums emerged, eager to prey on grieving widows and mothers longing to contact a lost loved one.

Houdini knew all the tricks used to establish the presence of spirits (floating tables, ghostly apparitions, savvy guesses) and was appalled by the deceptions. On the other hand, there were true believers like Houdini’s onetime friend Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes and one of the most credulous men Houdini had ever met.

Mr. Begley is enlightening in providing the context in which mediumship was perceived as an open question — something that could plausibly turn out to be as genuine as gamma rays, radio waves, or other recent discoveries. To put it to the test, Scientific American magazine offered a $2,500 prize to anyone who could produce “mediumistic phenomenon” under controlled conditions. Houdini was one of the judges, along with a few (utterly unqualified to detect fraud) professors, scientists, and academics.

Space does not allow a full accounting of the explosive events that followed, but it’s all here, in riveting detail: the intrigue and infighting of the committee, the Doyle/Houdini friendship turned bitter feud, the clash between Houdini and Mina Crandon, a seductive Boston socialite who channeled the sprit of her dead brother, Walter (a foul-mouthed, anti-Semitic Houdini-hater), and almost claimed the $2,500 prize, if not for Houdini.

As a result of the Scientific American investigation, Houdini was enjoying new respect as an educator and began crisscrossing the country, lecturing at universities and performing his full-evening show. It was during this tour that, weary from years of nonstop performing and punishing self-abuse, he was stricken with appendicitis. Willful as always, he refused treatment until it was too late. He died on Halloween in 1926.

So what is the legacy of this man’s remarkable life? Mr. Begley devotes his last chapter to a generous sampling of assessments from biographers, historians, therapists, and others who have made Houdini their subject (there are an estimated 500 books about the man!). Many relate his astonishing popularity — he was the most famous, highest-paid entertainer of his time — to the symbolism of his performances. Here was a man who shed not only literal chains and shackles, but the shackles of poverty, bigotry, and immigrant identity to become the American dream incarnate.

But as Mr. Begley points out, none of this was intentional. “He never asked to be a poster boy for freedom,” nor was he motivated by “a desire to improve the lot of his fellow man, or any other altruistic urge.”

“Perhaps the most useful verdicts are the simplest, verdicts that take Houdini at face value, as a spellbinding performer who carved out for himself a niche in show business history by escaping from every conceivable constraint.”

And here’s my verdict. Mr. Begley’s book is terrific.

Allan Zola Kronzek is the author of “Grandpa Magic,” a book of magic tricks and brainteasers. He lives in Sag Harbor.

Adam Begley’s previous books include “The Great Nadar: The Man Behind the Camera” and “Updike.” A former writer at The Star, he is a regular visitor to Sagaponack, where his parents have a house.