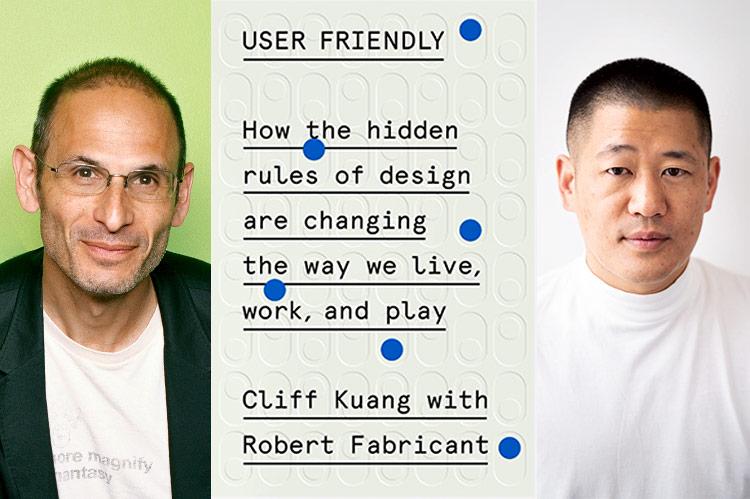

“User Friendly”

Cliff Kuang and Robert Fabricant

MCD Books, $28

One might hope that along the way in our fictional future past, someone would have streamlined access to a foolproof shutoff valve. A better button, right? But just 11 years after that landmark film, it was a stuck-open relief valve that ushered in the country’s most dire nuclear accident at Three Mile Island just outside Harrisburg, Pa.

“User Friendly: How the Hidden Rules of Design Are Changing the Way We Live, Work, and Play,” written by Cliff Kuang, a journalist and designer, with Robert Fabricant, an innovative leader in human-centered design and co-founder of Dalberg Design, starts here, with an exhaustive analysis of the 1979 nuclear meltdown in Reactor 2 at Three Mile Island. Exactly what went wrong?

After extensive research, the cognitive psychologist Don Norman (he invented the term “user experience”) determined that a poorly designed and ambiguous control panel led to confusion among the plant operators, all highly trained. Norman’s team eventually advised the industry how to improve the design logistics, and the reactors were retrofitted with an upgraded and more intuitive operating system. You might be surprised to know that while Reactor 2 sat lifeless for some four decades, Reactor 1 continued pumping out energy until it closed in September of last year.

The authors move through the history of design, highlighting key aspects of its triumphs and catastrophes, foibles and advancements. This sweeping investigation combined with an insider’s perspective and a keen sense of the industry at large drives this complex, sometimes overwhelming story. “User Friendly” offers a new benchmark in the study of user-experience (UX) design.

What is it? It’s the way the Bell 500 telephone receiver could be cradled in your neck, the New York City subway map, your television remote control, Facebook’s “Like” button, and everything else that defines our daily technological, ergonomic, and metaphorical experiences. If it strikes you as a bit chilling that a gaggle of M.I.T. graduates is designing the new world, maybe you’re not alone. But it’s hard to argue that a technology driven by user experience that ranges from the length of your fingers to predictive psychological algorithms is anything but universal advancement. I think.

While achievements in design are well known, the back stories are a fascinating amalgam of trial and error, economics, social progress, and the evolving definition of usability. If the 18th and 19th centuries brought us the Industrial Revolution, the 20th century was the dawn of “industrialized empathy,” a term coined by Mr. Kuang.

In this regard, the authors delve into the rise of user-centered innovations, taking us from World War II radar systems to the application of metaphor

in Apple’s extraordinary product development. Its ingenious “desktop,” “mouse,” and file system provided mental models for what a thing is and how it works. Today, if a technological device lacks that element of rapport between machine and human, it seems ham-fisted and virtually obsolete.

In the 1950s, postwar America identified a new consumer: the stay-at-home wife and mother. Armed with contraceptives and the right to vote, this new generation of women had both purchasing power and a modern longing not to be tied to the house. The advent of home economics was born, much through the efforts of the pioneering designer Henry Dreyfuss, who is considered at length here.

Women demanded intelligent products, streamlined usage, and, whether they realized it or not, a functional interface based on intuition. In other words, a better, user-centered design. Dreyfuss and others set to improving the design of washing machines, vacuum cleaners, waffle irons, and thermostats, and they all became easier to handle, more attractive, and less expensive. The overall mission was to create improved communication between the object and the user. No small feat. American design virtually upended the Bauhaus assertion that “form follows function.” You might say the U.S. replaced it with something more akin to “form follows empathy.”

The industrialist Henry Ford, founder of Ford Motor Company and advocate of mass production and the assembly line, revolutionized the automobile industry by creating the Model T and making it affordable to the American middle class. It was a fabulous success. Ford, who famously said, “Any customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black,” saw no need to update the design of his lucrative, unchanging Model T. Recounting its history, the authors describe the brief but near total decline of Ford Motor Company, whose dominance in the American car market suffered a distinct collapse when General Motors developed a wide selection of colorful new models. Ford retooled and redesigned, boosting the company’s sales with the release of the Model A, a bow to consumer desire and marketing.

Cut to the advent of driverless cars in this century and the risks escalate precipitously. Beyond financial jeopardy, questions of liability and infallibility loom large. Can a computer-driven car be hacked? What happens if its sensors are blinded by snow? Does it have eyes? Will it interact with you or me in the front seat, or does it drive better if it’s in complete control, unfettered by human instinct? Most important, can it be trusted?

But there is another, murkier idea related to A.I. referred to as an automation paradox. Research on how airplanes function has hinted that the use of artificial intelligence in the cockpit has made pilots less capable over all. If there’s no need to apply critical thinking while piloting a plane, the pilots become unprepared to react effectively when problems occur. Is technological design moving too fast? I’m not sure we can answer that question. But in this regard, Mark Zuckerberg’s early and often-used motto, “Move fast and break things,” might be better left in the 20th century.

Robert Fabricant has spent summers in East Hampton since he was a child.