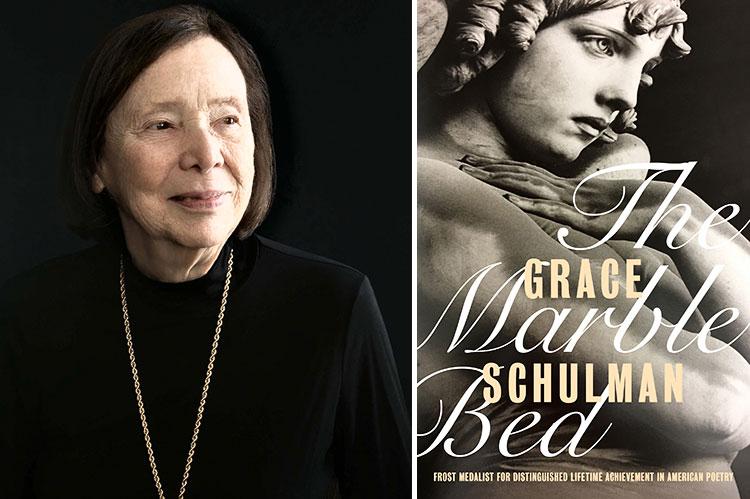

“The Marble Bed”

Grace Schulman

Turtle Point Press, $18

Poet, teacher, mentor, denizen of Washington Square and Springs and the world, journeyer, homebody, and 57-year veteran of marriage Grace Schulman casts her steady eye on mortality in her new collection, "The Marble Bed." Or, more accurately, she casts her eye on the things around her — a shirt, a jetty, funerary art — and they describe mortality back to her.

Much as the scenes and objects in an Elizabeth Bishop poem challenge her perceptions, Ms. Schulman's poems travel through their description, arriving, often, at praise. This is true even when the description is painful; that shirt is her husband's, but he is no longer alive to wear it. The fact of his death permeates "The Marble Bed." So, too, does her own, even though it hasn't happened yet.

Nonetheless, these poems are joyful, reminding us of how remarkable mortality is, how remarkable that, while alive, we are so tangibly, so factually here, just like our shirts and our music collections and our daffodils, how remarkable that we remain cognizant of our impermanence, even while our senses tell us the opposite tale.

"Nothing is new," Ms. Schulman writes. "Nothing alive cannot be altered." Some of that alteration is damage, the wear and tear of aging, the injuries we suffer, both physical and psychic, but the ultimate alteration is, of course, death, which changes us from animate objects to inanimate ones, the most wondrous transformation of all. And what could be more suitably expressive of our consciousness of mortality than a double negative, as in "Nothing alive cannot be altered"? It is only one of many linguistically aware lines where the rhetoric mirrors the sentiment.

Early in the collection, a poem called "Because" builds itself out of subordinate clauses, each beginning with the title word, that conjunction of cause and effect, to explore this problem of our "wounded universe." Set inside the successive "because" clauses are snapshots of city life in progress, full of sensory detail, each containing elements of beauty and of ruin: "because in a smoky bar the trombone blares / louder than street sirens" is an example. To what calamity are those sirens heading, even as the pleasurable music drowns them out? The poem resolves its poem-length sentence, with cause turning to effect, in its final lines, "because I cannot lose the injured world // without losing the world, I'll have to praise it."

Praise she does, in poems set on the East End, in New York, in Italy, in art museums and concert halls, in her own memory and history writ large, and in her lifelong love affairs with her husband and with books. For Ms. Schulman, reading and writing are ways to imagine beyond the borders of perception, to Hamlet's "undiscover'd country, from whose bourn / No traveler returns."

Journeys to the afterlife require guides, and Ms. Schulman has several: a gaggle of musicians and visual artists, from 16th-century Dutch still-life painters to Mahler and Sonny Rollins; Walt Whitman; Ezra Pound, that difficult figure of talent, madness, and anti-Semitism, and, especially, Dante Alighieri, whom she evokes throughout this collection. Characters from his "Inferno" appear in her poems, for example, and many of her poems are organized into the three-line stanzas, called tercets, that Dante uses in the "Divine Comedy." To remove all doubt, a number of the poems in tercets, including "Because," break their form to end with a single, isolated line, exactly as Dante ends each of his Cantos.

But in important ways, Ms. Schulman's book is an argument with Dante — a friendly parting of ways. Her tercets don't follow his strict terza rima, instead opting for a looser approach to sound. Elsewhere in the book are highly patterned, rhymed, metered poems, like "Ballade for the Duke of Orleans," that contrast with her more rugged approach in the tercet poems. Where Dante helpfully provides God with additional design suggestions for heaven and hell, where he offers rigid hierarchies and a comprehensive theological system of punishment and reward, Ms. Schulman stays firmly rooted in this irregular, "injured" world, gesturing toward the afterlife from the messy, secular, sensory, time-bound vantage of life above ground.

Take the poem "El Greco's Vision of Saint John," for example. In it the speaker, viewing El Greco's unfinished painting (our first clue of an "injured world"), steps aside so that a woman in a wheelchair (our second clue) can see. The woman raises her arms to the painting in a gesture of praise. While we can speculate that the woman is experiencing a religious rapture, the poem is describing her human hands, rather than that vision, for "perfection / is never the end-all, not even in heaven." This is the heart of Ms. Schulman's argument with Dante. Bloodless religious concepts like perfection and immortality are not an even trade with the joy of looking, listening, breathing in, and touching, no matter how much grief and trouble our mortal coils bring us.

Read this collection if you, too, have grieved. Read it if you need your own guide to the underworld. Read it if you've ever felt proud to get at the meaning of poems, of art, of music. Read it if you want to be restored to the world around you, if late-stage capitalism or imperialism or politics have numbed you. Read it, then look up, breathe in, raise your own hands, and let Grace Schulman assure you:

I'll be there,

gazing impiously — unless

that is what sacred is, the work, the looking up,

the wonder.

Julie Sheehan is the author of the poetry collections "Bar Book" and "Orient Point." The director of the B.F.A. program in creative writing at Stony Brook University, she lives in East Quogue.

Grace Schulman, who has won a Frost Medal for distinguished lifetime achievement in American poetry, will read from "The Marble Bed" over Zoom for the Amagansett Library on Nov. 18 at 5 p.m.