Officials Respond To Student Suicides

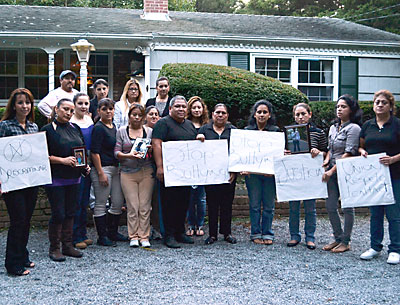

Three South Fork students — who were Latino — have committed suicide since 2009, prompting school and mental health professionals to call the need for increased outreach to that community especially acute. As the population has grown, Eric J. Bartky, a psychiatrist who counsels children and adolescents from his office in Southampton, cautions that the number of full-time mental health practitioners is too small. Besides financial costs, he said that transportation — or simply getting there — is often the biggest hurdle that young people face. In late November, Emilio Padilla-Berrezueta, an 18-year-old junior at Southampton High School who was days away from transferring to East Hampton High School took his life. David H. Hernandez, an East Hampton High School junior, died at home on Sept. 29. And Tatiana Giraldo-Fajardo, then 17 and a senior at East Hampton High, died at her Montauk residence in December of 2009. “Having three suicides in such a short period of time in such a small community is alarming. We’re very concerned,” Dr. Bartky said. As a practitioner, he was familiar with the circumstances surrounding David’s suicide, he said. “It highlights the strong need for better mental health services in the community to treat this underserved population.” Dr. Bartky, Gail A. Schonfeld, an East Hampton pediatrician, and Harriett L. Hellman, a pediatric nurse practitioner based in Water Mill, are part of the East End Pediatric Advocacy Workgroup, which helps provide quality mental health care to those who cannot afford it. A large portion of their clientele is Latino. Having been a practitioner in New Jersey and northern Manhattan, Dr. Bartky, who is fluent in Spanish, reports that the children he counsels on the East End report far greater degrees of trauma. Each year, from Hampton Bays to Montauk, Dr. Bartky conducts between 20 to 25 psychiatric evaluations for local school districts. “For the children, their journeys to the United States — especially if they’re undocumented — are filled with horror stories,” Dr. Bartky said. “It’s a journey filled with trauma, of learning a new language, of learning to fit in, and of oftentimes feeling less than.” Nothing in their prior work history had prepared Adam Fine and Maria Mondini, the principal and assistant principal of East Hampton High School, for David’s death in September. Although they have been school administrators for a combined total of more than a decade, having come to East Hampton from Southampton in 2010, they said his suicide shook them to the core. In the weeks following David’s death, Mr. Fine received as many as 30 e-mails a day from companies selling educational programs — on everything from anti-bullying to character education to suicide prevention. But rather than opt for a panacea, Mr. Fine decided to consider the problem more deeply. “We could do a Band-Aid program or we could take the pressure and weather the storm and do what’s right,” he said in a conversation late last month. Or, as Ms. Mondini put it: “Are we doing everything we possibly can to make sure this never happens again?” The hope of several school administrators and parents is that the recent suicides will precipitate real change by shining a light on troublesome corners of school life that may have been overlooked. Those interviewed by The Star said they were taking the long view of school change — one where the culture of East Hampton High School might be altered for the better three to five years down the line — rather than opting for a hurried and superficial overhaul. “We need people to open our eyes to all of the blind spots,” Ms. Mondini said, noting that all egos needed to be placed aside, whether those of administrators, parents, or students. “There are always blind spots but the question is: Are you willing to be shown them and then, once you have them, what are you willing to do with that information?” A concerted effort has begun to reach parents of Latino descent in the East Hampton community, where Spanish is increasingly the primary language spoken at home. According to the 2010-2011 New York State District Report Card, which is the most recent available, 38 percent of students in the East Hampton School District identified as either Latino or Hispanic. Following David’s suicide, the school convened a steering committee of students, parents, administrators, and clergy to tackle the question of how best to proceed. Ultimately, the committee decided on a school-wide survey — an anonymous, 20-minute questionnaire that addresses such topics as support, security, and diversity, among other factors. The district also increased outreach to Spanish-speaking parents in other ways. In December the district hired Ana Núnez as its liaison to that community. A Columbia University alumna, Ms. Núnez graduated from East Hampton in 2007. She had arrived in East Hampton from Ecuador at the age of 9. The new position for the district pays an annual salary of $19,300 and is funded through a Title I grant. Since being hired, Ms. Núnez has convened a handful of meetings with Spanish-speaking parents at the high school. More than 100 parents turned out at a mid-February session, which offered complimentary child care by students in exchange for community service credits. Coming up on Feb. 28, Ms. Núnez will host a session for parents of children at John Marshall. Patricia Hope, a retired East Hampton High School teacher who is a member of the school board, is responsible for bringing Ms. Núnez to the attention of the district. Ms. Hope had taught Ms. Núnez science. Sitting in the Golden Pear in East Hampton near the end of last year, Ms. Hope recalled the “scales falling from her eyes” when she heard Ms. Núnez describe the dire need for increased outreach. “It opened my eyes to a situation that as a resident, as an educator, and as a board member I should have been more sensitive to all along — namely, the needs of any population, small or large, that does not speak the language,” Ms. Hope said. “I realize that we need to serve them in a more day-to-day, immediate fashion. We need to do a better job of reaching out.” Marcia Dias, a bilingual secretary in East Hampton High School’s main office, is a member of the steering committee. She said she has seen increased Latino parent turnout at meetings. Having them conducted entirely in Spanish, she said, has proved enormously helpful in helping to bridge the chasm. “One of the things parents would always tell me was that they wanted to go to the meetings but they couldn’t understand what was being said and they didn’t feel comfortable speaking up,” Ms. Dias said. “We’re now telling them that they can be part of this community and that we need their support in order to make the school better.” But David Kilmnick, chief executive officer of the Bay Shore-based Long Island Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Services Network, cautions against placing all the blame on the schools. Prior to committing suicide, David Hernandez had walked into a meeting of the Gay-Straight Alliance at East Hampton High School. Mr. Kilmnick described East Hampton, when it comes to anti-bullying, as among the “most progressive and assertive on all of Long Island.” “School can have 100 workshops a day and 100 clubs but that’s not going to change the environment when the kids leave the school and they have to face bullying and homophobia in their churches and their local communities,” Mr. Kilmnick said. He is now trying to set up a community center for gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender youth “somewhere between Southampton and Bridgehampton.” Ms. Hellman, the nurse practitioner in the East End Pediatric Advocacy Workgroup, suggested the center be named for David Hernandez. As of yesterday morning, nearly all the staff members at East Hampton High had completed the steering committee’s survey, along with 14 percent of the high school’s parents. (The survey has been made available in Spanish as well as English.) Following next week’s winter recess, students will be asked to fill out the surveys during class time. The National School Climate Center, an organization based in New York City that helps schools establish an environment of emotional well-being, is administering the survey. Included in the $3,000 cost, the center will compile the results and conduct a thorough analysis before presenting the findings to the committee in the spring. Depending on the outcome, the district will weigh whether or not to conduct a similar survey at East Hampton Middle School and John M. Marshall Elementary School next year. In a letter sent home to parents in early January, Mr. Fine said they would be invited to attend a community meeting to discuss the results once the report was received, which he hopes will be this spring. We “hope you will join us in this effort to make our school an even better place to learn,” he wrote.