Alive and ‘Weird’ in Sag Harbor

Alive and ‘Weird’ in Sag Harbor

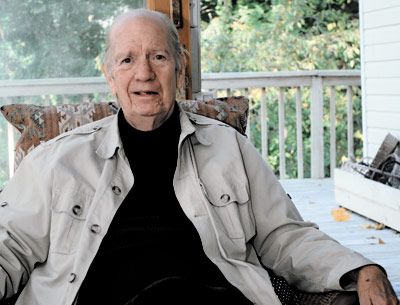

Anybody who has flipped through The New Yorker or Playboy during the past 50 years has encountered the cartoons of Gahan Wilson, instantly recognizable for their black humor and bizarre and often grisly images. Mr. Wilson is frequently referred to as “a master of the macabre,” and rightfully so. It is, therefore, something of a surprise that his Sag Harbor house turns out to be not a crumbling, overgrown castle with grotesque monsters glaring from the windows, but rather a bright, charming place with neither a dungeon nor a ghoul in sight. Last week, Mr. Wilson was present at the John Jermain Memorial Library in Sag Harbor for a screening of Steven-Charles Jaffe’s documentary “Gahan Wilson: Born Dead, Still Weird.” According to his wife, Nancy Winters, a writer, “Gahan will wear his cape — which he never likes to do.” The film’s title refers to Mr. Wilson’s entrance into the world, which the cartoonist has described thus: “Gahan Wilson, nephew of a lion tamer, descendant of P.T. Barnum, was born dead. After 10 minutes of rigorous alternate dunkings in hot and iced water he reluctantly came to life. He suspects there may have been brain damage.” Not to be outdone, Ms. Winters, asked how long she has been living in Sag Harbor, said, “I’ve been coming here since I was a baby. I was swept out to sea when I was 6 at the Prospect Hotel, which used to be on Shelter Island. I was walking out, got caught in the tide, and I was too shy to cry for help.” Neither Mr. Wilson nor Ms. Winters seems the worse for these early ordeals. Mr. Wilson’s unconventional birth took place in Evanston, Ill., in 1930. His father was an executive with the Acme Steel Company, and both parents were talented amateur artists. As far back as he can remember, Mr. Wilson loved to draw. “I never had any other ambition,” he said over iced coffee and a muffin. “That’s what I wanted to be, that’s what I was going to do.” After a year in a conventional high school, Mr. Wilson transferred to the Todd School for Boys in Woodstock, Ill. Roger Hill, who became headmaster in 1921, rejected examinations and traditional academics in favor of practical experience. “It was a wonderful school,” Mr. Wilson recalls. “They encouraged you in whatever direction you wanted to go.” Another famous alumnus was Orson Welles, who often returned after graduating to see student productions, stroll the campus, and dine with the students. Mr. Wilson went from high school to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he earned a B.F.A. degree and, in 2012, an honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts. His many other awards include the National Cartoonists Society’s Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award and the 2004 Life Achievement Award from the World Fantasy Convention — the other winner that year was Stephen King. Mr. Wilson also designed the award for the World Fantasy Convention, a bust of H.P. Lovecraft, the writer in whose memory the first convention was held. “It actually looks like him,” said Mr. Wilson. After college, “It was pretty clear that if you wanted to do magazine cartoons, you had to go to New York,” recalled Mr. Wilson. He started out with small magazines, where cartoonists were expected to bring, and present, their work. “They either go for it, or they don’t,” Mr. Wilson said. “But within a few months, I was able to support myself. I’ve had a lot of lucky breaks.” Even at The New Yorker, cartoonists, no matter how eminent, bring their work in each week for the editor’s judgment. It’s a very sociable world, according to Mr. Wilson. “Cartoonists all know each other. There’s no competition, no plotting or claiming to belong to a superior school of cartooning. Experimentation is welcome by everybody.” Mr. Wilson’s first Playboy cartoon appeared in the December 1957 issue. In 2009, Fantagraphics Books published “Gahan Wilson: Fifty Years of Playboy Cartoons,” a three-volume, slip-cased set. “He hasn’t missed an issue in half a century,” wrote Hugh Hefner, editor and publisher of Playboy, in an introduction to the first volume. “He is, in many respects, one of a kind. The readers love him, and so do I.” While his palette expanded over the years — it was Mr. Hefner’s idea to limit it at first — Mr. Wilson’s drawing style and demented sense of humor were fully formed from the very beginning. Not surprisingly, among the artists Mr. Wilson most admires are Goya, Daumier, and Hogarth. He also recalled a used bookstore in Evanston where, at the age of 15, he discovered Punch, a satirical British weekly magazine established in 1841. It was most influential in the mid-19th century, when it helped to coin the term “cartoon” in its modern sense as a humorous illustration. “I bought the entire shelf, for 15 cents an issue. It was an enormous influence on me.” Asked how he gets an idea, Mr. Wilson said it was difficult to describe the process. “You start with a subject — maybe something in the newspaper. It’s a free-floating thing. You sort of go into a trance. It’s really fun and occasionally downright thrilling.” And, yes, he does laugh at his own cartoons. “Whether it’s laugh or be scared, if it doesn’t do it for me, it won’t do it for anyone else.” As the conversation wound down, Ms. Winters appeared with a small piece of paper, approximately 2 by 4 inches, torn from a memo pad. Sketched in ink was an overhead view of a railroad station platform and tracks Mr. Wilson made while waiting for a train in Westport, Conn. “Something on the tracks caught his attention,” said Ms. Winters, though it was difficult to tell what it was from the drawing. “It’s a sketch for a New Yorker cover,” she added. “Only if they decide to use it,” Mr. Wilson added. Keep your eyes peeled.