Shanghaied

Shanghaied

“The Last Whaler”

Nicholas Stevensson Karas

AuthorHouse, $25

When I checked my morning mail several months ago, I was surprised by a large mystery envelope. I was delighted to see it contained a local historical novel. These are rare creatures out here on the tip of Long Island; not as rare as academics trying to put into words our underpublished history, but still rare enough to cause me to look it over before placing it on my stack of evening reading.

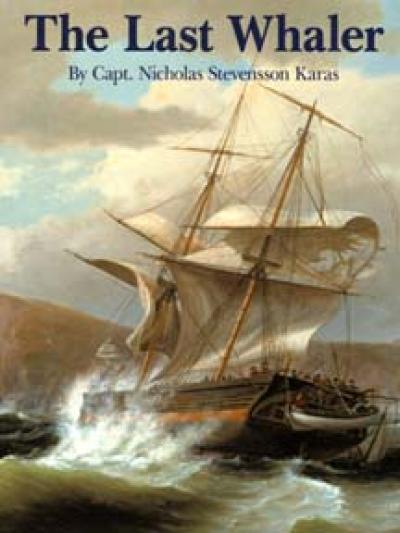

The stunning painting on the cover of Capt. Nicholas Stevensson Karas’s second novel, “The Last Whaler,” is a dynamic 1841 oil by Thomas Birch, a Philadelphia artist. The finesse that this British-born painter used to delineate the power of a stormy sea and the vulnerability of the ship’s crew is an invitation to an adventure. Though the cliché regarding books’ covers and contents is well worn, Captain Karas uses words as well as Birch’s image to draw us into his tale: “A historic novel based on a true whaling adventure of a Shinnecock Indian as told to a Long Island merchant seaman. The events took place between 1865 and 1942.” These lines, printed across the angry green ocean on the cover, are as seductive as the art.

Melville produced one of America’s greatest novels, mixed with allegory, using men, the sea, and a white whale. I certainly wasn’t about to prepare myself for a new “Moby-Dick,” but a whaling story revolving around a Shinnecock seemed to offer ample possibilities. Whaling, after all, is as operatic as business can be. And the cover did say “based on a true whaling adventure.”

After dinner I sat down, ready to entrust the author with the ship’s wheel. Now I should explain, I am a historian specializing in the East End of Long Island. I enjoy both fiction and nonfiction. I expect historians to back up their theories with primary source material, but I understand that novelists should invent and embroider because they are storytellers and mythmakers. All that said, I became disappointed with “The Last Whaler” quite quickly. I blame the cover.

The prologue is filled with misinformation, and there seems no logical reason to set such a false stage for a story purported to be based on fact. The author has Long Island’s East End settled in the 1670s instead of the 1640s. He has our first mainland settlements established by Quakers rather than Puritans. And mixing up Sag Harbor with the Massachusetts island of Nantucket, Captain Karas has the first local whaling captains as “ever-industrious Quake entrepreneurs.” The author has created something called “the Company” — “a loose assortment of ship owners, ship chandlers, whale oil supportive industries, retired whaleship captains, widows and farmers and fisher Quakers” — which controlled what was left of Sag Harbor’s once giant whaling industry. There is no evidence that such an organization ever existed, and what history has passed down to us portrays the typical Sag Harbor captain or whaleship owner as independent and proud of it.

The most slippery historical slope that Captain Karas climbs is his creation of a myth about Shinnecock sailors. It is known that the native people of Long Island’s East End were famous for their agility at capturing whales by boat offshore. Early local historians have recorded that the Shinnecocks and Montauketts were quick to teach the colonists their fishing techniques. Beginning in the early 19th century, any perusal of whaling logs here supports the role of natives as crew members. Indeed, several Shinnecock whalemen became famous as harpooners and boatmen. What seems an invention is the author’s premise that the crew of a whaleship would consider “jumping ship before it departed because no Indian” was on board. There is no question about the respect crews had for the prowess of native people as whale hunters. But while this myth has no grounding with historians, it is crucial to the narrative.

“The Last Whaler” is very engaging as the author paints a gray-green film over the once proud Village of Sag Harbor. The year is 1865 and the country has changed forever with the close of the Civil War. Change had already started to erode this famous whaling village. Petroleum had erased the value of whale oil. Whalebone was still needed by the New England corset and umbrella manufacturers, but the four-year whale oil journeys, around the tip of South America up to the Bering Sea, were obsolete. Watchcase making would soon help Sag Harbor, but that is the next chapter.

The village was haunted by its days of wealth. The streets were darkened. The parlor doors were closed tight, and the rosewood suites of carved furniture shrouded with bed sheeting. The old men and women who remained (they had nowhere to go) clanked about like strings of bones or fallen wind chimes. This is where we meet the remains of the Company, holding on to a past that has long ago evaporated. Though historically several more whaleships would leave the harbor, the author smartly takes 1865 as the year of the end.

The Lester brothers, Andrew and Hiram, along with a cousin, Ephraim Brown, have convinced the last of the Company to repair and outfit the old whaling bark Tranquility for one last try at a hold full of whale oil with a trip down the coast of South America possibly as far as the Falkland Islands. As the plans are laid and the ship is readied, the living ghosts of the community seem to feel a cold sense of good riddance rather than farewell.

Finally a patchwork crew is assembled, but will they sail without the mythic Shinnecock? A plot is formed and 15-year-old Benquam is kidnapped and taken aboard just before the Tranquility sets sail. The trip is a bumpy one for Benquam, the captain, the crew, and the reader.

It is a story of mourning, regret, ego, murder, kidnapping, pride, and revenge. The dialogue is very carefully written, but wooden. As to the dialect, a great deal of research was most likely done by the author. But the language is not colloquial; it tends toward lecturing to inform the reader of period nautical terms and activities. The plot is fast paced and grows much faster as the novel nears its end — a race that seems to end abruptly. The characters do grow on the reader, but they lack rounding and rarely surprise us. Once in their personality boxes, they remain there.

With 30 years under his belt as a licensed captain, the author knows modern boats and has carefully studied how a whaling bark was crewed. Some of his best writing involves the very detailed description of just how the Tranquility was sailed.

Our young Shinnecock gets put aside as the story becomes more visceral. Benquam is really a device for starting and concluding the dramatic tale. During an almost cinemagraphic storm sequence, I could not put the book down. But hanging over this novel is the assertion that the narrative is based on fact and not fabrication. Does it make any difference? Would the story be better if Benquam had really existed? I think yes.

Captain Karas has written an engrossing story that could have been richer. I wish the author had taken advantage of a proofreader, editor, and historian. I think that a historian could have helped turn the book’s factual messiness into a real and useful introduction to the South Fork’s whaling story.

And I would strongly suggest that the book need not mislead the reader by touting any resemblance to “a true whaling adventure of a Shinnecock Indian as told to a Long Island merchant seaman.” This is pure imagination. No Shinnecock historian, no whaling history maven, no local historian or Long Island maritime museum director has ever heard this tale, and certainly the author adds no footnote or other source to document this fantastic yarn about a young Shinnecock boy being kidnapped in 1865 and discovered on an island in 1942 alive and well. Let fiction be fiction.

—

Nicholas Stevensson Karas was an outdoors columnist for Newsday for many years. He lives in Orient Point.

Richard Barons is the executive director of the East Hampton Historical Society. He lives in Springs.