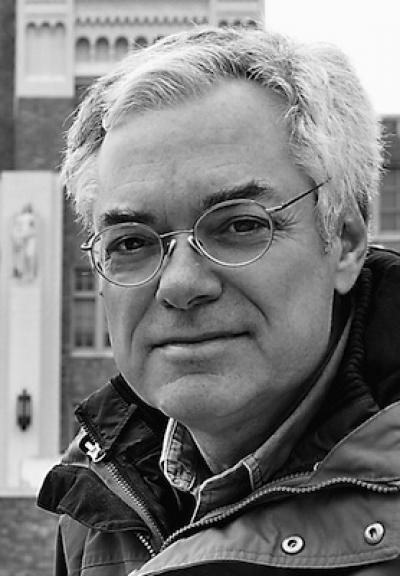

Carl Safina At Writers Speak

Carl Safina At Writers Speak

Carl Safina will read from “The View From Lazy Point” on Wednesday at 7 p.m. for the Writers Speak series, sponsored by the M.F.A. program in writing and literature at Stony Brook Southampton. The free event will take place in the Radio Lounge, upstairs in Chancellors Hall.

Mr. Safina, a past MacArthur fellow, is president and co-founder of the Blue Ocean Institute in Cold Spring Harbor. His PBS series, “Saving the Ocean,” premiered last spring.

A half-hour beforehand, there will be a discussion of this year’s Southampton Arts Summer, which used to be called the Southampton Writers Conference — an assortment of July workshops on theater, film, visual arts, and writing.