ROUNDUP: From Parasites to Plotlessness

ROUNDUP: From Parasites to Plotlessness

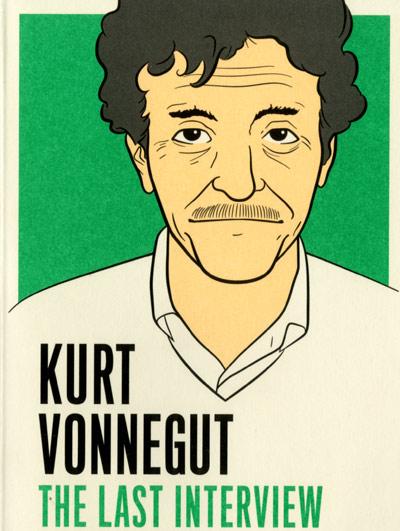

Has a writer ever been more productive in death than Kurt Vonnegut? It’s a mini industry, from posthumous collections of his unpublished short fiction (“Look at the Birdie,” “While Mortals Sleep”) to the hefty Library of America volumes of his life’s work, the most recent of which, “Novels & Stories, 1950-1962,” came out in April. In October, Delacorte will release a book of his letters and Vanguard will publish “We Are What We Pretend to Be: First and Last Works.”

And, somewhat under the radar, there came the slim “Kurt Vonnegut: The Last Interview and Other Conversations” (Melville House, $15.95).

Oh, it’s all here, the irascibility and constant funk, for instance, great fun to read: “My country is in ruins. So I’m a fish in a poisoned fish bowl,” he told U.S. Airways magazine in June 2007. Or his World War II experience: “What they wanted when they successfully invaded Europe was a whole lot of riflemen to sweep across the continent. So that’s what I was. . . . The things I saw as a private — I wouldn’t miss it for anything.” So recorded the journal Stop Smiling in its August 2006 issue.

His famously dim view of humanity is leavened with insight, as when, also in 2006, he spoke of the super rich and the White House leadership at the time: “They were born without a conscience. They’re psychopathic personalities. . . . They don’t care what happens next. They rise high in business because they’re so decisive.” Where a normal person might express some doubt, “A psychopath would say, ‘Here’s what we’re going to do. Bang.’ ”

When it comes to writing, Vonnegut’s traditionalism is on display. “I guarantee you that no modern story scheme, even plotlessness, will give a reader genuine satisfaction, unless one of those old-fashioned plots is smuggled in somewhere,” he told The Paris Review in the book’s earliest interview, from 1977. “It’s the writer’s job to stage confrontations. . . . If a writer can’t or won’t do that, he should withdraw from the trade.”

Vonnegut, who lived in Sagaponack all those many years, died in April 2007 at age 84, about two months after he spoke to In These Times for a brief online interview, his last. In it, he’s asked about his childhood in Indiana, which leads him to, of course, lament something — rampant loneliness, “the great American disease” — and yet his response has all the sweet nostalgia of Bergman’s “Wild Strawberries”: “And at Lake Maxinkuckee there were a row of cottages, one of which we owned, and so I was surrounded by relatives all of the time. You know, cousins, uncles and aunts. It was heaven.”

“The Great Moviemakers”

“In a way it’s sort of like having filet mignon for dinner every night,” Steven Spielberg said in 1978 of his seven-year contract with Universal Studios. “You forget there’s Nathan’s on Ventura Boulevard, that there’s Carl’s Jr. . . .” That appreciation of the gravy train is from another book of conversations, George Stevens Jr.’s “The Next Generation” (Knopf, $39.95), which across 700 pages compiles interviews conducted at the American Film Institute with “The Great Moviemakers: From the 1950s to Hollywood Today.”

The director goes on to explain the benefits of having television as a training ground before reminiscing about his breakthrough feature, “Duel,” in which Dennis Weaver is terrorized by a faceless, murderous trucker, and detailing at length the writing and shooting of his triumphant “Jaws.” “It’s probably a terrible thing to say,” he goes on, “but there were so many similarities between ‘Duel’ and ‘Jaws.’ I felt ‘Jaws’ would be the sequel to ‘Duel’ in disguise.” And an auteur is born.

Mr. Spielberg, who has a house in East Hampton, is one of several movers and shakers in the movie biz who have or had a presence on the South Fork. Particularly of note are interviews with those who are no longer around to be interviewed, like Nora Ephron, who also lived here. She discusses her long transition from journalist to screenwriter to director of hit romantic comedies.

“Out of the Woods”

It’s that time of year again — for a good walk spoiled. No, not golf. The sense is that you’re taking your life in your hands by so much as setting foot in any wooded area, crawling as they are with pestilent deer ticks. Is the solution really white tube socks pulled knee-high a la Dr. J of the old A.B.A. Nets?

A new book by Katina Makris, a healer and homeopath, is mostly a memoir of a struggle with illness but also a guide book and resource for dealing with Lyme disease. In “Out of the Woods” (Elite Books, $18), Ms. Makris details years of torment at the hands of a mysterious ailment that she later learned was Lyme. It affected her family life and her work before spurring her to a campaign of research, activism, and alternative-medicine healing practices.

Toward the back of the book is a compendium of useful information, from signs and symptoms to a discussion of bacteria and laboratory testing to an array of treatment options. Ms. Makris, a former East Hamptoner who now lives in New Hampshire, will speak about all things Lyme in two stops on the East End, at the library on deer tick central, Shelter Island, at 7 p.m. on Aug. 17, and the following day at Canio’s Books in Sag Harbor at 5 p.m.

Maybe you should listen up. That or take a cue from Woody Allen — just stay in and order Chinese.