Bullets and Bons Mots

Bullets and Bons Mots

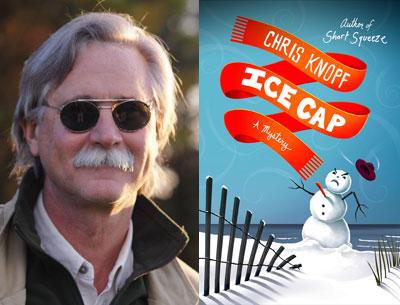

“Ice Cap”

Chris Knopf

Minotaur Books, $25.99

You’ve got to hand it to Chris Knopf: He knows how to have fun. His prose vaults across the page with happy confidence — though I suspect he doesn’t waste much time analyzing his characters’ deepest motivations, let alone plot developments that are more convenient than believable.

In his new mystery, “Ice Cap,” the characters are there to amuse. They are a semi-noir cast with advanced degrees, who channel their underused intelligence into nonstop wisecracks and literary references. If the author feels a gun battle might spice up his heroine’s afternoon, then a gun battle it is. Doesn’t every girl lawyer need her own Glock — particularly if her practice was formerly in Hamptons real estate?

“Ice Cap,” the third in Mr. Knopf’s series of Jackie Swaitkowski mysteries, satisfies many elements of the beach read — a little romance, a puzzling mystery, a fair amount of diverting comedy. It has the added virtue, for those who are reading this, of unfolding at a beach community near you, from the mean streets of Southampton, down Montauk Highway, to Amagansett, where after nightfall you’d apparently be advised not to walk alone. Don’t go looking for familiar landmarks, however. This East End is being blanketed by so many blizzards, it might as well be Buffalo.

On the day in question, Jackie Swaitkowski takes a call from a client, Franco Delano Roosevelt, who looks as though he might be facing a murder charge. Following a rich tradition, Franco, a former Wall Street hotshot, is a closet sweetie in spite of the rough exterior. Nonetheless, he has spent time in the slammer some years ago for killing his former girlfriend’s husband with a rotisserie skewer.

Since returning from upstate, Franco has suffered reduced circumstances. He has been working as a handyman for Tad Buczek, a Southampton “artist” who has sold off most of his family’s vast potato fields. With the millions he’s collected, Tad has turned what remains of his property into a kind of personal theme park, replete with massive scrap metal sculptures rigged as water fountains.

By the time the curtain rises, Tad Buczek is as dead as a doornail. Franco has managed to muck up the crime scene by dragging Tad’s inert body out of the field where he “stumbled” over it covered with snow. Did Franco murder Buczek or not? That he’s cuddling up with Zina Buczek — the deceased’s sexy Polish mail-order bride — doesn’t look good in his police file.

But what kind of mystery would this be if the most obvious suspect was actually the murderer? As “Tad never tired of pissing people off,” there is no shortage of possibilities. There’s his association with Ivor Fleming, the scrap metal king of a Russian/Polish underworld — though the motive for murder, in this case, is hard to pinpoint. And how about the neighbors, who might have offed Tad to hold on to their property values? Finally, there is the Buczek family, not a single member of which held Tad in high regard.

Before he’s done, Mr. Knopf introduces such a staggering array of characters that you’ll need index cards to keep them straight. At the center is Jackie, an attractive, late-30s-ish widow, the book’s Nancy Drew, who is related to the victim through her late husband. When Jackie’s not driving her Volvo over snowbound roads, she’s in her flannel pajamas, working out of the office in her apartment above a Japanese restaurant. (This is no glamour Hamptons mystery.) She is conflicted about her boyfriend, sorely needs a decent hairstylist, and so enjoys her cocktails that I fear in future books we will find her at A.A. meetings. Endearingly, Jackie confides in her readers, even as her career as a laid-back Hamptons criminal lawyer strains credibility.

Wherever Jackie Swaitkowski goes, so goes the snappy dialogue. After she orders a bottle of wine for herself in a restaurant, a snotty French waiter counters with, “Our least expensive wine? We have a mediocre blend from a struggling vineyard that we’ll likely not source from again. I’m sure it will suit Madame perfectly.”

The most unlikely characters quote Winston Churchill, refer to Kublai Khan, use Latin expressions like in flagrante delicto, and sling irony with the ease of jaded intellectuals. The goons (“meatballs who work as muscle”) shadowing Jackie leave a warning note on her car signed, “Your Reverse Guardian Angels.” Surely, a goon this sophisticated can find a better line of work. Or maybe not in the new economy.

The dialogue is not just witty, but occasionally wise. “Everybody can get lonely, Jackie,” says Franco, explaining his affair with Zina. “Doesn’t always mean they want to become your soul mate.”

In the final analysis, Mr. Knopf hasn’t quite decided if “Ice Cap” is a mystery or a no-holds-barred comedy. If it’s the former, then the plot feels a bit lazy, which robs the narrative of urgency. Since it’s going nowhere special, you want him to wrap things up and get to the big reveal. A comedy, on the other hand, would need to be broader, quirkier, and more over the top — a la Carl Hiaasen, which it resembles, but in northern climes.

On the strength of its dialogue, however, “Ice Cap” could have a brilliant future as a feature film. With clever casting, characters who sound similar (albeit witty) on the page would become distinct, and implausible scenes might benefit from some good old-fashioned physical comedy.

Ellen T. White, former managing editor of the New York Public Library, is the author of “Simply Irresistible,” a humorous how-to that culls the lessons of the great romantic women of history. She lives in Springs.

Chris Knopf has a house in Southampton.