A Touch of Meta

A Touch of Meta

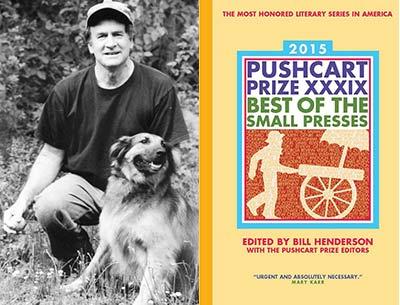

“Pushcart Prize XXXIX: Best of the

Small Presses”

Edited by Bill Henderson

Pushcart Press, $19.95

It is Pushcart Prize time again, and those who await the collection will do well to find a bookmark and a cozy spot. Pushcart editors have dipped into the independent and small magazines as a pool and come forth with a thick, healthy offering.

Looking into the fiction in “Pushcart Prize XXXIX: Best of the Small Presses” is especially gratifying because a unity emerges in the writers’ attention to story. Well, they are short stories, true, so they tell stories in one way or another, but the best in this volume of bests attend to story as a concept, as a theme. In some selections it is explicitly front and center, and in others it waits in corners, in the midst of other subject matter and various backdrops: family, “Madame Bovary,” homelessness, driving, the World Wide Web, divine parentage or the question of it, music, suicide, football, rock climbing, the perspective of the loved one of a stripper, dogs.

I do have to make sure to mention the dogs. There are four stories in this collection in which a dog plays a major role as a metaphor. But not by any means the same metaphor, in case you worried Bill Henderson was slacking in his duties as Editor and Duke of this enterprise. He’s on top of it in this volume, as he has been for the 39-year duration of the series. Thank you for doing this, sir.

One of those dog stories, “Trim Palace” by Alexander Maksik, which was first published in Tin House, is among the finest pieces here. It is carefully and elegantly written, humor subtle, images concrete. In it, Peter, in his 30s, has lost his way in life and is working as a janitor at an airport. On the job, he runs into an old friend with whom he’s lost touch. The friend has a pretty wife, a sleek cellphone, important places to be. His question to Peter is, “I got to ask. Short version, okay, but, what the fuck happened?”

How does a person’s story become so? At what point is the story over with no possibility of a new direction? Peter accepts a house/dog-sitting job from the friend and finds himself taking care of an aged Great Dane, metaphor for fragility and power and the potent but vulnerable force of a life. There’s a tender quality here, an optimism; it is written with rare respect for human potential for regeneration. I read in the contributors’ notes that Mr. Maksik is the author of two novels. So I’ll be looking for those.

In this edition of the Pushcart Prize, story is treated variously as a fragile and complex human drive, a way to brilliantly organize human suffering, as a dot-connecter in an increasingly fragmented landscape of text, blurb, post, tweet. In light of the last, “The News Cycle” by Daniel Tovrov, which first appeared in ZYZZYVA, is an absurdist riff on reporting, reality, and responsibility in the age of the He or She With the Greatest Number of Hits Wins world of news on the Internet. Pacing-wise, the piece takes the shape of the news cycle, revving up, wheeling off, moving on.

It’s fair to say that the fiction in this volume — not every single story, but a critical mass and several of the essays as well — goes meta. A case in point is Maribeth Fischer’s essay “The Fiction Writer,” first published in The Yale Review, which deals with the pull and seductive danger of story in the psycho-emotional sense. Ms. Fischer’s piece is about storytelling in the hands of a pathological liar who inhabited her personal and professional life for a time. A self-avowed successful fiction writer, this person serves in the essay as the nugget around which Ms. Fischer’s ruminations on storytelling and the magnetism of belief swirl and roost. The piece somehow warms and chills at the very same time. Fascinating, and expertly executed.

When it comes to meta and stories, there’s the danger that the going can get clinical, fussy, arch, know-it-all. It can get terribly self-conscious, and one of the volume’s most effective stories examines this very pitfall. The main character of “Unmoving Like a Mighty River Stilled” by Alan Rossi, from The Missouri Review, takes up the case of a semiprofessional rock climber who is having major issues with one of his climbing partners and a piece of equipment called a “helmet cam,” the current tool of his climbing partner’s insistence that all of their adventures be captured on video, to be posted as brag and record and proof that the glory happened.

The story is sunk deeply into the narrative voice of the main character, detailing his discomfort and his self-consciousness in the many other postures of his life, which have somehow come together on the issue of the helmet cam, of representing an event rather than purely living it.

The writers represented in this year’s Pushcart volume share a commitment to the work at hand. As a reader, the experience of immersion is authentic, palpable. For example, and maybe back to the potential pitfalls of meta in fiction, these writers are not messing it up with gimmick or posture.

“By the Time You Read This” by Yannick Murphy, which originally appeared in Conjunctions, maybe verges on that but snatches itself back from the jaws of shtick with rare charm, unexpected innocence, and reality hilariously hosted by absurdity. Ms. Murphy’s story is told in epistolary past tense as a series of fragmented suicide notes to various recipients from an unnamed woman, who is the enraged wife of a cheating husband. The method of suicide shifts from fragment to fragment, and the note-writer’s rage is pure yet totally distracted by the minutae of life (e.g., the dog who needs her second dose of heartworm medicine) and her own frequent digressions. Ms. Murphy’s effort is clever, compact, and really, really funny.

The charm and pull, balm and elixir of story are well represented by these pieces. Pushcart once again makes a good showing of what’s out there, what the independent and small magazines are offering readers. It’s a volume full of work that intrigues, engages, gets you with a good story.

Evan Harris, the author of “The Art of Quitting,” lives in East Hampton.

Bill Henderson’s latest book is “Cathedral.” He lives in Springs.