A Selfie, in Words

A Selfie, in Words

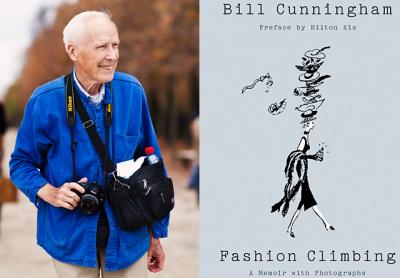

“Fashion Climbing”

Bill Cunningham

Penguin Press, $27

Anna Wintour, Vogue editor and arbiter of style, once said, “We all get dressed for Bill.” Indeed. To have your picture taken by Bill Cunningham, New York’s original street-fashion photographer, who believed in ordinary people’s self-expression through clothes, was certainly a feather in one’s cap. He democratized fashion by showing that style wasn’t dependent on money or status, and his weekly roundup of street fashion in his long-running New York Times column, “On the Street,” featured every age, race, gender, creed, sexual orientation, and even our four-legged friends. For him, it was about the statement, the confidence of the wearer, and not much else.

Mr. Cunningham died in 2016 at age 87, taking photos for his column right up until his death. And it was only then, with some surprise, that his family discovered he had secretly written a memoir.

“Fashion Climbing” was released last month during New York’s Fashion Week. But much like the 2010 documentary “Bill Cunningham New York,” which he reluctantly allowed to be made, the book isn’t so much about fashion as it is an affectionate telling of the journey of a gentleman who found true beauty and joy within the frivolity of fashion and became a modern-day anachronism.

The story begins in his “middle-class Catholic home in a lace-curtain Irish suburb of Boston.” In the summer of 1933, when Mr. Cunningham was 4, his mother caught him parading around in his sister’s dresses. She gave him a thrashing and threatened to break every bone in his body if he ever wore girls’ clothes again. Naturally, it had the opposite effect.

Forced to attend a trade high school, where his parents hoped the boy’s artistic tendencies would be curbed, Mr. Cunningham found his calling in an after-school job at the newly opened Bonwit Teller branch on Boston’s Newbury Street. Working as a stock boy and helping during the store’s fashion shows by taking photographs with a $5 camera, he learned one of his greatest lessons from Mrs. Rosalind DeHart, the store manager: “She showed me how to observe every woman I saw, seeing how she was dressed and accessorized, and then taking her apart in my mind’s eye and putting the right kind of clothes on her.”

After a two-week, all-expenses-paid stint at Bonwit’s New York store, the company offered him a prestigious scholarship to Harvard, which he likened to prison. He gave up on academia and fled back to New York in 1948, where he took to life “like a star shooting through the heavens.”

Much of the storytelling depicts a young man of irrepressible exuberance. His unflappable spirit and constantly sunny disposition lend a sort of charming, slightly soft-in-the-head quality to the narration. But he also throws in a few meaningful revelations, like this one, which comes closest to shedding light on his sexuality, a topic about which he was famously guarded:

“It’s a crime families don’t understand how their children are oriented, and point them along their natural way. . . . The country would not have half the trouble with mentally disturbed people it has if parents would accept each child’s God-given personality and stop trying to force what they feel is more suitable for their offspring.”

There’s a lot about hat making and his millinery trade in this slim, 200-odd-page memoir, with photographs to show that he was essentially a designer of truly kooky head-toppers.

East End readers should delight in a wonderfully entertaining chapter titled “The Southampton Shop.” By the mid-1950s, Mr. Cunningham had a robust New York millinery business, which he operated under William J., leaving out his last name to avoid further embarrassing his parents. Having developed a popular line of “beach hats” — a photograph shows an octopus hat with tentacles swooping down across a face, and another with a fish perched atop a model’s head with its body and tail trailing down her back — the author decided he would sell them in Southampton, “the watering spot of the New York Social Register.”

He rented a tiny shop on Job’s Lane across from the old Parrish Art Museum for $1,000 for the summer and filled the window with his whimsical creations, much to the horror of the conservative Southampton dowagers, who found them vulgar and blamed the hats for a sudden influx of prostitutes to the genteel village.

The shop, which was adored by the young and the eccentric, lasted four summers. By 1960, Mr. Cunningham noticed a stark shift in fashion. Young women had stopped wearing hats, and William J. closed for good. But no matter, because as he was dismantling his store, Women’s Wear Daily called looking for a fashion photographer.

“Fashion Climbing” is a lovely glimpse into the life of one of New York’s most celebrated shutterbugs, a master of invisibility in an industry full of people who long to be seen. But mostly it is simply a joy to read because its storyteller was so very, very charming.