The Test of Time

The Test of Time

You might say that this edition of The East Hampton Star HomeBook is dedicated to teardowns.

No, not because any of the houses we are featuring are about to be demolished, or because any of them rose from the ashes of demolition, but because they have survived this 21st-century trend toward extinction.

So, here’s to houses worth saving!

One survivor comes by the word “cottage” historically. Some 200 years old, it rests not far from the ocean in Sagaponack, where most of the other old, salt-air summer cottages that were constructed relatively recently, in the 1940s and 1950s, have been expanded and reconfigured beyond recognition.

Another is the only house remaining on the South Fork designed by the renowned late architect Andrew Geller. The 1968 Geller house, in Springs, was recently purchased by a television producer and his wife, who respect its playfulness and plan to restore certain aspects of the original that had been altered under previous owners.

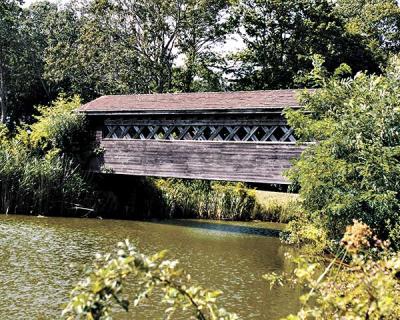

Then there’s an abode, jammed full of needlework and other artistic handiwork by one of its owners, that started out as a 19th-century barn. Yet another place of interest we feature is what you might call a South Fork folly: Hidden from view — except from the houses at Ludlow Greens, a subdivision north of the highway in Bridgehampton — it isn’t a house, in fact, but a covered wooden bridge of the kind you may have seen in the Meryl Streep/Clint Eastwood film “The Bridges of Madison County.”

The newest house in this HomeBook is fascinating (among other reasons) as an example of how to make creative use of awkward building lots, as open space dwindles. The architect Blaze Makoid and the landscape designer Jack deLashmet devised a way to make beautiful use of what others had found troublesome: a small lot shaped like a slice of pizza.

In the spirit of good stewardship, we hope you find this issue of HomeBook not just entertaining but inspiring.