200 Years of Peace

200 Years of Peace

Long Island from the beginning has had a close relationship with England. On Dec. 24 the United States and Britain celebrated 200 years of unbroken peace.

The peace treaty, the Treaty of Ghent, came after a long period of hostilities. We were on the same side during the French and Indian War, when the wise Prime Minister William Pitt the Elder chased the French out of North America. But as soon as Prime Minister Lord North and George III tried to make the colonies pay for their own protection, the American Revolution was on.

Its end was not the end of hostilities with the mother country. James Madison declared war on Britain in 1812 because British Orders in Council made it harder for the United States to trade with France, and because the British Navy was seizing (“impressing”) sailors on colonial ships and putting them on Navy ships. The British ended the trade restrictions, but not impressment.

After Britain invaded and burned the White House and Capitol, it became clear that this was a war that neither country could afford — Britain was richer but it had been spending a lot fighting Napoleon. In the fall of 1813, Lord Castlereagh, the British foreign minister, offered to negotiate. The two countries picked neutral Ghent in eastern Flanders as the venue.

The United States team was led by John Quincy Adams, son of a president and himself destined to become president. Henry Clay played the role of hawk, or “bad cop.” The rest of the team was Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin, the Federalist James A. Bayard, and Jonathan Russell, who was U.S. chargé d’affaires in Paris. It took the Americans six weeks or more to communicate with Washington, D.C., so they were negotiating largely independently to restore territory to what it had been before the war, the “status quo ante bellum.”

The British team was led by Lord Castlereagh and Lord Bathurst, secretary for war and the colonies, but they did not attend the talks. Instead, a less skilled admiralty lawyer, Williams Adams, an impressments expert, Admiral Lord Gambier, and the undersecretary for war and the colonies, Henry Goulburn, pursued a goal of “uti possidetis” — each side keeps what it had won militarily.

The outcome of the treaty was favorable for the United States, perhaps because the war was going well for the Americans at the time the treaty was signed.

The Americans had been losing early on, but Lt. Gen. Sir George Prevost was faced in Plattsburgh with a strong New York and Vermont militia and U.S. Army regulars under the command of Brig. Gen. Alexander Macomb. Failing to take Lake Champlain, the British fled north after the battle. Next, Fort McHenry in Baltimore withstood a severe attack and inspired the national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

News of these two battles was the last information that negotiators in Ghent received.

The British lost their goal of making the Native American lands in the state of Ohio and in the territories of Indiana and Michigan a reserve that would be a buffer to protect Canada from American annexation. They got none of the other aims of their invasion.

On Dec. 24 the negotiators agreed on the 3,000-word treaty. After approval by the two governments, hostilities ended and “all territory, places, and possessions whatsoever, taken by either party from the other during the war” were restored to what they had been before the war.

Donald E. Graves, a Canadian historian and War of 1812 expert, concludes that what Americans lost on the battlefield, “they made up for at the negotiating table.” Although the United States never got the British to promise not to impress American sailors, with hostilities in Europe ended this ceased to be a concern.

It took a while after the signing of the treaty before the combatants got word, however. The British attacked New Orleans on Jan. 8, 1815, with a large army. It was overwhelmed by a smaller and less experienced American force under Gen. Andrew Jackson in the greatest U.S. victory in the war. News of the treaty and the outcome in New Orleans reached a delighted American public at about the same time.

The War of 1812 greatly damaged the Long Island economy. A blockade was maintained at Gardiner’s Bay that led to several clashes between American and British vessels. Many vessels were hidden in inland harbors on Long Island or on Carmans River in Connecticut.

The American privateer Governor Tompkins captured a number of British ships. On its way back to New York, the ship confronted an English brig of war and had its bowsprit shot away and five men killed or wounded. New York City was blockaded at Sandy Hook, so the Tompkins tried to make New London. Seeing the British fleet waiting there, the Tompkins changed course and went through Plum Gut, then a narrow rocky strait between Plum Island and Orient Point, where the brig could not follow. Daniel Winters of Westhampton guided the Tompkins to safety in Gardiner’s Bay.

A big loss for the British occurred on Jan. 16, 1815, three weeks after the Treaty of Ghent. The 22-gun British sloop of war Sylph, with a crew of 121 men, got lost and went ashore off Shinnecock Point. Volunteer rescuers gathered, but the high wind, heavy surf, and a blizzard prevented a lifeboat from being launched in a timely way. By the time it got to the wreck, only one officer and five men remained to be rescued. A letter from the British Admiralty with the Suffolk County Historical Society says the Sylph lost at least 115 men, including the captain and 10 other officers.

The 21 bodies that floated ashore are buried near Sugar Loaf at Shinnecock Hills, and the wreck is commemorated by a tablet in Southampton’s St. Andrew’s Dune Church. The border and wheel above it are made of red cedar from the vessel’s wrecked timbers.

The Treaty of Ghent has held up for 200 years. But it did not imply an immediate “Special Relationship,” just a cessation of hostilities. In fact, many Irish Catholics opposed the U.S. entry on the side of Britain in the Great War. The famed Special Relationship was really not cemented until the threat of Hitler brought together the United States and Britain, first with Lend-Lease and then with the U.S. declaration of war in 1941.

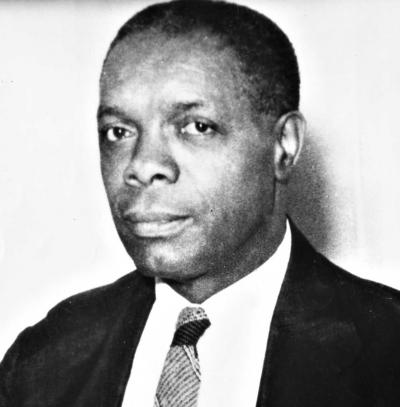

John Tepper Marlin is president of Boissevain Books. He has lived in Springs since 1981.