The Password Is . . . Hell!

The Password Is . . . Hell!

Remember game shows? “Concentration,” “The Big Payoff” (with a former Miss America, the late Bess Myerson, in a pre-feminist mink coat)? Remember “What’s My Line?” and “I’ve Got a Secret”? “Queen for a Day”? “You Bet Your Life”? I do.

And quiz shows like “The G.E. College Bowl” or “Twenty-One”? Game shows, quiz shows — you and your family can feud over the distinction and which falls under which genre. But, for the most part, they have given way to reality shows that aren’t really reality.

I mean, how real was Bruce Jenner all those years with all those Kardashians, when, out of the blue, he declares he’s about to undergo a gender reassignment? That we never had a clue? Frankly, with his Peggy Fleming kind of hair back in his reality days as an Olympian, in his short shorts a la Richard Simmons, we should have guessed. But that’s another story left for Diane Sawyer to gather and uncover.

Of course, there is still “Jeopardy!” and the annoying “Wheel of Fortune” and “The Price Is Right,” but that last one is just not the same without Bob Barker, or, prior to him, Bill Cullen. “Let’s Make a Deal” is dull without Monty Hall. “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire”? I’d rather watch “How to Marry a Millionaire.”

And then there was “Password.” Allen Ludden, the host, dead a century, and his wife, as a contestant, Betty White, living approaching a century, with the odd way the off-camera announcer would tell, no, whisper the password to the studio audience and those of us viewing at home: “Sh-h-h. The password is . . . ubiquitous.” (Try that one on for size — Soupy Sales, a contestant on the offshoot “Password All-Stars,” would have a struggle, as anyone would, with that.)

The password is ubiquitous. And this is where I shift gears and segue and transition to the real point of this piece: passwords!

In fairness, and with ease, the password to unlock my iPhone, when it was the 4 and the 5 and now the 6 Plus, has always been the same. Four measly digits. Just four. No symbols, no combinations of numbers and letters. Easy. Breezy. Memorable. In fact, the same four digits I use at a cash machine.

Beautiful.

But every other password I need — to get into my Chase account online, to sign onto Amazon, to log on for my 401 balances (which I do daily, and you would too if you were retired, as I am, as I have been for three years now) — requires, no, demands difficult combinations: no less than eight characters, no two letters in a row the same, a cap, some lowercase, a symbol, a number or two. Then, to make matters even more humiliating, they tell you (They? Who are they? Some little people inside the laptop, or even littler people inside the phone?), “Your password is weak.” Or “not strong enough.” I need criticism that I am inadequate from an inanimate object? Believe me, I get enough from my life partner.

Netflix, on my smart TV, makes me feel like an idiot. You have to use the remote to scroll up, down, and across to hit the precise password, which I never remember.

Facebook is another killer in the random way it asks for a password. Generally, you just go to the app, but occasionally, and for no good reason other than Mark Zuckerberg is a genius and we are all morons and he constantly throws it in our faces, they ask for a password. “Your login has expired.” Why? How come? Don’t f**k with us, Zuckerberg. We are not as clever or as brilliant as you. I barely know how to work the electric can opener! (Full disclosure: That last line was stolen from a Woody Allen movie.)

But it gets even worse. Yes, it does. If you want to order something online, or respond to a friend’s article, or comment on how despicable technology has become, you are required to type a code of letters and numbers that run together, smash into each other, to prove you are not a robot or a monkey. Believe me, monkeys would be more adept as deciphering those indecipherable collections of numbers and letters. Uppercase? Lowercase? I wind up, after half an hour of ordering this watch or that pair of jeans, frustrated and canceling my cart. I just can’t make out the strung together, no, squashed together, code. Plus, my fingertips are too fat.

How many times have you wanted to toss a device out a window when you are told that after three attempts and failures you need to reset the password? And then you get a series of numbers as a temporary password, brief seconds to find a pencil, write it down, and make the effort to change.

The Notes app on my iPhone has a tab titled Passwords. It currently has 28 passwords listed, most already obsolete.

Pandora and iTunes and PayPal and Ticketmaster and Skype. There are also accompanying pins attached to a bunch of them. Twitter and Cargo and J. Crew and God Knows. That last password number never works. Because God, nor anyone else for that matter, knows how or why the universe of passwords has become so . . . hellish.

There should be a new quiz show or game show, a la “Name That Tune.” “I can name that password in four numbers combined with letters and symbols.”

Oh, @#!+*%& it. I can’t.

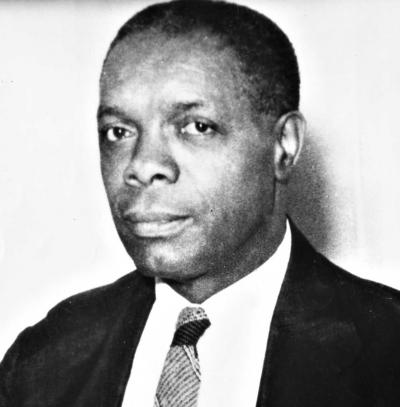

Hy Abady is just out with a new book, “Back in The Star Again, Again!” — a sequel to his 2010 collection of “Guestwords” and “True Stories From the East End.”