Roll on, Ye Olde Firetrucks, by Jeff Nichols

Roll on, Ye Olde Firetrucks, by Jeff Nichols

To be candid, I walked into the Southampton Antique Firehouse (yes, there is one, and it is fully functional) with a singleness of purpose: to sell them a comedy show.

As I once was a comic based in Manhattan, I sometimes, with enough prodding, can get old comic friends to travel from the city to do a fund-raiser out here. The shows are a lot of fun, and I charge a slight fee for putting them together. I get posters made and put them up, and so on. My old high school friend Chris Gaynor, a longtime Southampton volunteer firefighter and contractor, gave me the lead that the department was entertaining the idea of putting on such an event. When I arrived, I imagined I would see a couple of tough-looking guys, possibly with pronounced beer bellies, holding wrenches, hanging around some dilapidated old truck, saying, “We need money to fix this thing but we got none!” I expected to feel intimidated by “real men”; I can barely change a flat and am always hiring men to fix stuff at my house as I make them lemonade.

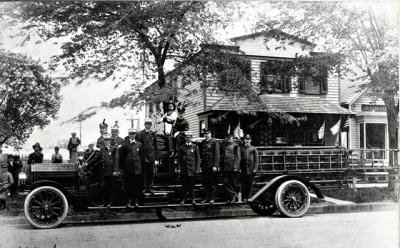

But as soon as I entered the spotless garage on Flying Point Road, around the corner a ways from the Princess Diner, I was transported into another world. I know that’s a cliché, but it’s also the truth. I was blown away, to fall back on another cliché. There before me were four or five immaculately preserved antique firetrucks, magnificent, proud anachronisms, serving as sparkling, tangible proof of the past. The Hamptons’ past.

Southampton is well known for the sprawling, garish estates that now occupy what used to be farmland, but, considering history and time served, I would submit that these trucks should be the stars of the Hamptons.

The 35-foot American LaFrance Type 14 city service hook and ladder truck, which arrived in Southampton in 1913 (it took three days to drive it out — I wonder if there was backup at the Lobster Inn), was the first firetruck model in America with a gas engine. It cast a particular spell on me: I could visualize firefighters from days gone by scurrying about it, taking ladders off, then trying to scale burning buildings to save people or douse a flame with foam from a copper canister that hung from the side.

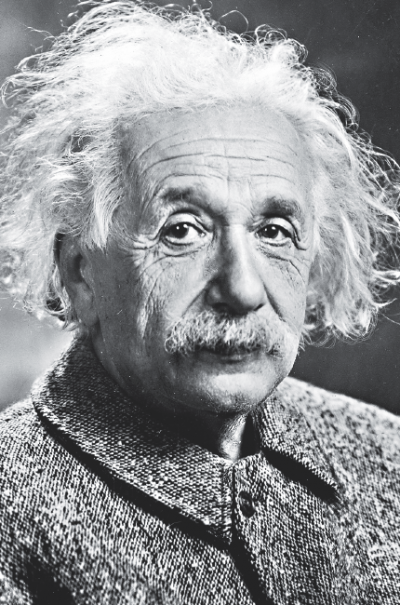

The guys who met me were warm, educated, and obviously very competent. Craig Raynor, the president of the Fire Department’s antique truck committee, and Bobby Cox gave me a tour. The first question I asked was: Why was this not open to the public? Apparently they do have designs on a museum, and I think it would be a damn good one — but of course that requires more funding.

Right now they are just trying to keep the trucks running so they can compete in shows and serve the community. To date, the trucks have been shown at various festivals nationally (often winning best in show) and at local parades, funerals, and other events.

Simply put, these guys, Craig and Bobby, know firetrucks. It is beyond a hobby for them; it is their life. From the model numbers to the engines down to the ornamental copper and brass fittings, they know where each piece was manufactured. The trucks, all a-glimmer, looked in such fine condition that they did not seem to need any repair — not to the layperson’s eye, specifically mine.

What needed to be fixed? That was a Pandora’s box: “Well,” Craig said, “this fender here is dented and is not an original. We have to keep these authentic or we can’t compete . . . and look at the decolorization here, and that paint’s hard to find and match, but we will find it. . . . And this truck needs a whole new windshield, and we have to get the brass canister’s copper finished, and this windshield is completely missing; it will take one hundred calls to track one down. And if we don’t replace the engine mount on the Model 250, which already has a crack in the block, then. . . .”

And here lies the problem and the need for modest funding: As things go, time goes by. The people who built and designed these trucks are of course long gone, but what’s worrisome is that the generation that inherited the firetruck “culture” has aged, too. According to Craig, there was once a functioning and robust mechanism in place to serve as a distribution network of dedicated firetruck preservationists. It used to be that if you needed a part, all you did was call a distributor and get it, or someone would know where to go for it or whom to call and ask. But now there are fewer parts distributors around.

And, according to Craig, it is harder and harder to get young people interested in working on these trucks. “A lot of the guys have died, and the parts get lost along the way,” he said. “The parts are not on eBay. The young guys don’t know how to work these old block engines like the ones before the Model Ts. They’re all about computers now.”

Now here is where this all gets even more interesting. Before the mass-produced Model T, some engines in the early 1900s had only one or two pistons. Today, if you crack a block (break the engine) on one, there is only one guy to call in the tristate area: Tony Guarnaschelli. He is 80 years old but still works on trucks.

His secret if the engine block is cracked completely? He puts them in a tractor-trailer and takes them to Lancaster, Pa., of all places. Tony won’t tell you the address because, well, he doesn’t want to overburden the guy, but also because the guy who fixes his and hundreds of other departments’ engines meets him at the end of an unmarked dirt road in a horse and buggy and takes him up to his 5,000-square-foot garage loaded with old firetrucks and parts.

The Amish man is a welder by trade. Amish, you say? Electricity? How can that be? Apparently the Amish are allowed one electrical line, which they can run many tools off of, if used for work. No one else can weld like this guy, Tony said. “He will spend three days on one block. You can’t find welders around here that have that kind of time and dedication.”

Craig Raynor and his wife, Amy, travel all over the country with the trucks. One is a pumper truck from 1946 (in service till 1969) that pumps faster than any truck its size. Nice to see that the trucks are ambassadors of the Hamptons, and even though they have won countless awards and blue ribbons in competitions, and even though the hook and ladder truck appeared on the front lawn of the White House, the only press they have had before now was in 1913, in a newspaper called The Seaside Times.

So let’s keep those trucks moving and representing the past. The fund-raiser starts with a spaghetti dinner at 5:30 p.m. on Saturday at the Hampton Road firehouse. Dan Naturman and Lynne Koplitz will headline the comedy show at 8. Tickets are $40 for the show, $50 for the show and dinner.

Jeff Nichols is the author of "Caught: One Man's Maniacal Pursuit of a Sixty-Pound Striped Bass and His Experiences With the Black Market Fishing Industry." He lives in Springs.