Three More Sharks to Follow

Three More Sharks to Follow

Sendero Luminoso, the organization of Maoist revolutionaries of Peru, always comes to mind when I’m offshore on a boat that’s shark fishing. This only makes sense because of the dream state one drifts into while, well, drifting, as the crew spills ground fish and fish chunks overboard to create un sendero luminoso, a shining path that wanders toward the horizon as time passes, a route for hungry sharks to follow until they meet the boat’s baited hooks.

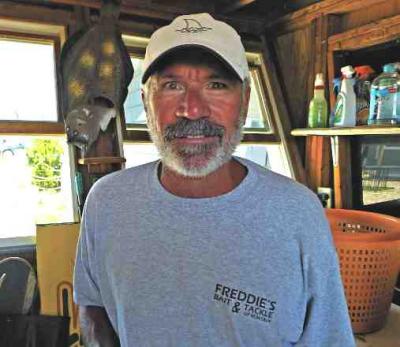

On Saturday, the shining path drifted west on the tide 14 miles south of Montauk Point from the Last Mango, one of the boats participating in this season’s Carl Darenberg Memorial Shark’s Eye no-kill tournament held from the Montauk Marine Basin.

In fact, revolution was in the air, and has been since the late Carl Darenberg, owner of the Montauk Marine Basin, broke with bloody tradition three years ago to create a catch-tag-and-release shark tournament with the help of a number of conservation-minded locals and the support of Jimmy Buffett, the Last Mango’s skipper.

Competing boats and the “chase boats” that observed and recorded the action fished both Saturday and Sunday. A total of 66 sharks were tagged and released. Sixty-two received conventional research tags to identify the time and place of their tagging in the event they are caught again. The dorsal fins of three sharks were outfitted with special GPS tags that will allow them to be tracked via satellite as they go about their normal migrations.

Twenty-two of the sharks were makos, 42 were blue sharks, and there was 1 thresher and 1 hammerhead, all tagged and released.

The Free Nicky boat, with Capt. Nick Raccanelli at the helm and Joe Gaviola and Jim Brown in the fighting chair, took top honors after releasing 14 sharks, one of which was a 175-pound mako that was fitted with a satellite tag and given the name Carl, in honor of the tournament’s founder.

Capt. Richie Nessel’s Nasty Ness with Dan Christman and Dave White on board took second place. The Nasty tagged and released 12 sharks. Third-place honors went to Capt. Gary Sevard’s Tiger Shark boat.

Capt. Dave Grimes’s Susan G satellite-tagged two sharks. The first was a 300-pound thresher, given the name Susan G. It was the first thresher ever to be given a GPS tag. The crew also attached a GPS tag to a 100-pound smooth hammerhead that they named Elijah.

The Montauk Marine Basin extended special thanks to the tournament sponsors, the Guy Harvey Ocean Foundation, Tom O’Donoghue and Associates, the Andrew Sabin Family Foundation, and the South Fork Natural History Museum, as well as Dr. Greg Skomal’s crew for attaching the three satellite tags. A closing statement from the Marine Basin read: “Lastly, we would like to thank Rav Freidel for coordinating the whole tournament. Without these people this tournament would not be possible.”

All three of the GPS-tagged sharks can be tracked on the Ocearch.org website. Carl, Susan G, and Elijah will also be tracked at the Montauk Lighthouse Museum’s Oceans Institute. Also known as the Montauk Surf Museum, the institute will celebrate a soft opening on Saturday evening with a screening of “The Endless Summer,” Bruce Brown’s surfing travelogue. The film that launched a million surfboards will be inducted into the Smithsonian Institution’s collection of important American artifacts next month in Washington, D.C. “The Endless Summer” first hit the big screen 50 years ago this summer.

The screening will be held outside on the north lawn at the Montauk Lighthouse. The gate opens at 6 p.m. to give visitors an opportunity to glimpse what’s in the works: the institute’s combination of surfing history and explanation of the natural forces behind surfing, as well as other coastal phenomena. The cost is $20 for adults, $10 for kids.

And, speaking of surfing, “Surf Craft: Design and Culture of Board Riding” will be presented at the Longhouse Reserve in East Hampton on Friday, July 31, from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m. Over 40 boards will be displayed, their shapes spanning the history of the craft of surfboard design.

On the way offshore on Saturday, shark boats passed a flotilla of smaller craft whose crews were busy angling for black sea bass, that delicious species. Simply remove head, gut, and scales, make three or four cuts on each side, place ginger slices in cuts, marinate in soy sauce, and bake. You’ll think you’re in Indonesia.

The split recreational season for sea bass opened on July 15 and will run until Oct. 31, then reopen from Nov. 1 until Dec. 31.

Besides the excitement over sea bass, sportfishermen have had big and very big bluefish to contend with. According to Paul Apostolides at Paulie’s Tackle shop in Montauk, the blues are ranging from 3 to 16 pounds, inshore, offshore, everywhere. Now, I know that not everyone likes bluefish, but I do when they are bled immediately after being caught and kept on ice. Duryea’s outdoor restaurant on Fort Pond Bay in Montauk is the only restaurant around that still serves broiled bluefish. Delicious. And, of course, smoked bluefish rocks.

Harvey Bennett at the Tackle Shop in Amagansett reports “fluke up to 24 inches” in Gardiner’s Bay and, speaking of bluefish, an earlier than usual run of snapper blues. “We have porgies, big porgies, and freshwater fishing has been unreal in Fort Pond.”

Oh, and a cautionary note: En route back to Montauk Harbor on Saturday, the crew of the Last Mango espied a man hanging on to his fishing kayak about a mile off the Point and heading south with the ebbing tide.

We picked him up, shaken, frightened, and thankful. He explained that his yak capsized when it met that dangerous combination of wind against tide. The fish well in the forward section of the kayak filled with water and he was unable to right it. He lost a $400 fishing rod and reel, but lived to fish another day. Fortunately, he was wearing a life jacket and wetsuit.

The moral of the story is this: Know where you’re fishing. The tidal rip currents around Montauk Point are extremely dangerous, especially for small craft, and especially for anglers who don’t do their research. In this day of GPS chart plotters, tide charts, and very high frequency radios that blare with marine weather forecasts, there is little excuse for not knowing the basics about the waters you’re entering.