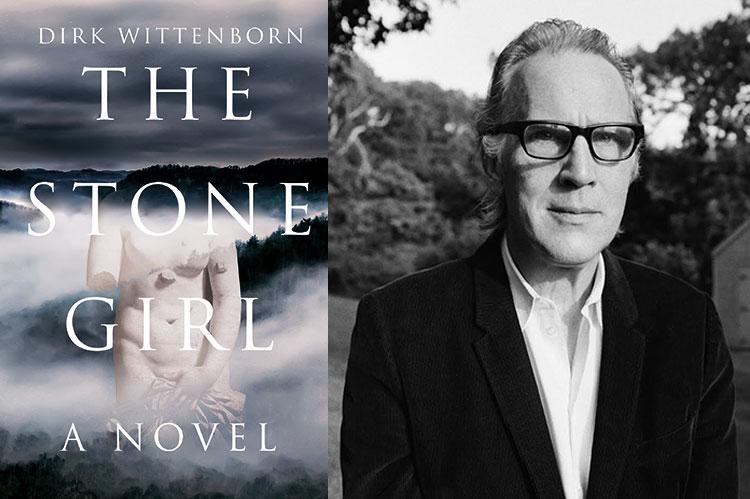

“The Stone Girl”

Dirk Wittenborn

W.W. Norton, $27.95

As I was reading Dirk Wittenborn's thriller, "The Stone Girl," my mind kept flashing onto an image of Thelma and Louise meeting James Dickey's "Deliverance" characters.

Yet in no way is Mr. Wittenborn's tale retro. Nor is it in the least derivative. The females in this book are strong and ever resourceful. The males, well . . . they're strong and resourceful, too. Although a large proportion of them are forces for evil. (No need for concern. I'm not going to need to issue a spoiler alert.)

Evie Quimby grew up hardscrabble poor in the Adirondacks with a port wine birthmark across one side of her face. She was adopted by Flo and Buddy Quimby, about whom Mr. Wittenborn writes: "Whether you believed the Quimbys to be weird, feral, dangerous, or simply aging hippies with a fondness for guns depended on what rumors you believed."

Taunted by schoolchildren because of her birthmark, she was pulled out of public school by her parents around age 10. Flo, feathers braided into her hair, had her daughter reading aloud classics such as "Pride and Prejudice." Meanwhile Buddy took Evie out day and night to catch fish and trap animals. He taught her about firearms, every rifle and pistol imaginable. Night-vision goggles. Taxidermy. All the ways of the wild.

Although the family's was a hand-to-mouth existence, Evie was able to earn money trapping and fishing and began saving every nickel. Her goal was $25,000, the cost of the surgery to remove her birthmark. Then at age 17 she was raped.

Evie meets a young heiress and widow, Lulu Mannheim, whose husband was found dead on their wedding day. (Nope. I'm not going to reveal how.) Lulu has nearly destroyed an ancient marble sculpture in her mansion, Valhalla. Evie, whose manual dexterity has been honed during all those years working with animals, takes the statue and puts it back together, and the two women become friends.

The East End makes a cameo appearance. As do France and Switzerland. But the bulk of the action resides in the beauty of the rough-and-tumble upstate mountains and rivers where fishing, trapping, and shooting are of paramount importance. Especially to the members of the Mohawk Club who go to the mountains for hunting and fishing, and some dastardly networking.

To get away from bad memories, Evie moves to Paris, where her reputation as an art restorer becomes legendary. She even repairs statues for the Louvre. But then her daughter, Chloé — yes, another strong female in this novel — is diagnosed with cancer, and she must spring into action to save her. When a man from Evie's past pays a mysterious visit to Chloé's Paris hospital room, Evie is jolted into a different kind of action. Evie realizes that the tentacles of a mega-rich cabal have international reach and she must return to the Adirondacks to avenge herself and protect her daughter. Lulu joins her in the fight because she has plenty of avenging to do as well. (Remember that fiancé?)

The book is breathtakingly cinematic. Plot complexity? Mind-blowing. Logicality? Impeccable. Metaphors? Strong. But the number of times I thought "No! Don't do that!" are too many to count. So much danger.

Full confession: I was nearly panting as I read much of Mr. Wittenborn's novel. Misdirection is a thriller writer's great tool. Had I understood all the lightning-fast twists? Had I gotten everything right? To be brought in as a co-solver is utterly satisfying. So when I read "The End," I turned back to the beginning. There's a brilliance in giving us early-chapter glimpses into what's going to happen later on — without telegraphing the future of the story. The aha, I get it! moments make a reader very proud.

Yet there are so many touches of wit and wisdom:

"You're not thinking about telling him?" Lulu watched as Dill [the sheriff] got out of the cruiser.

Evie shook her head no. "Like Buddy used to say, 'Putting off answering a sheriff's questions just gives the law more time to realize they're not asking the right questions.' "

A few days later, the same sheriff, Dill, still in uniform, is a fan at a girls' lacrosse game. "The crowd packed into the field house was three-beers rowdy and the score was tied. At that moment, [one] daughter's nose had just been bloodied and most likely broken by a slash that wasn't called." Parental language grew quite vulgar, "which Dill thought was rough talk for a girls' sporting event. He had already told them once to sit down and shut up. Unlike most county sheriffs, Dill found no satisfaction in arresting people for doing things he warned them not to do."

Just as "an eye-gouging brawl" starts up, Dill receives a call that means Evie is in trouble. As he's rushing to his cruiser, a woman indignantly asks why he isn't stopping the fight. " 'They're not in my jurisdiction.' But Evie Quimby was."

At the beginning of the novel, Evie, Flo, and Lulu erect a 10-foot obelisk, a marker, to Chloé. Evie terms it a "calling lure — an old-fashioned expression, commonly used by trappers. A calling lure draws a beast out of its lair and tempts it into a snare."

A month after the stone was put up, Evie, Flo, and Lulu "convened in the vegetable garden behind Flo's cabin. Misfortune had galvanized the bond between them by then into something that went beyond the categories of daughter, mother, friend. The women were finding out the truth about themselves. How far were they willing to go? How much were they ready to risk, when there was no making things right, just a remote chance of making them a little less wrong? Their troika was a democracy; the particulars of the damage that had been done to each made them equals."

The metaphor of the stone girl reverberates throughout. Someone who can be picked up and put back together. Again, this is not a spoiler alert. But everything in the end of "The Stone Girl" plays out to perfect imperfection.

Lou Ann Walker is director of Stony Brook University's M.F.A. program in creative writing and literature at Southampton and Manhattan. She lives in Sag Harbor.

Dirk Wittenborn is the author of the novels "Pharmakon" and "Fierce People." He summers in East Hampton.